This is the time of year nordic skiers are excited to really ramp up the hours and build that summer base. It’s also the time that in our excitement to do so, we get some kind of injury or aches and pains that slow this process down.

Years ago for me, it was an IT band, then shoulder, then Achilles. Many look at this as part of the process of being an athlete, each of the injuries due to too much too soon, just random pains and strains, right? Wrong!

In the seemingly randomness there is a pattern, it is just not apparent unless one understands the body’s movement patterns and what drives injury risk through muscle and mobility imbalances. Just because one is not injured does not mean an imbalance will not catch up to them at some point, be it with increased training volume, intensity or a different movement pattern, such as a change in technique or activity (switching form biking to running).

For many of us addressing imbalances will lead to improved movement efficiency, which will directly impact race times. Once the dysfunction is determined the imbalance can be fixed with an individualized strength, and mobility program. Hence these injuries are very preventable.

The muscles and joints getting injured are the ones that are usually working the hardest and pulling the weight of neighbors not doing their job. It’s kind of like that group science project where one or two members do the majority of the work and the others coast along. After a while, the one working hard either gets irritated or burnt out.

Now imagine this happening for the full semester. That is what happens to your body. A good example is low-back pain when you do your first long classic ski. Those muscles are working extra hard to keep your pelvis balanced and in position; that is also your abdominals’ job. If they are just along for the ride, guess what happens? Add tight hamstrings or hip flexors and it just accelerates the process.

For years we did stretches, back extensions and sit-ups and usually it didn’t fix much. Why? It never really addressed the root problem of mobility and stability imbalances.

The body’s musculoskeletal system (kinetic chain) mobility and stability are an interdependent foundation of all other aspects of fitness; one balances the other like a seesaw. When not fully developed (and this is the case in many elite athletes), we see injuries, technique deficits and minimal gains from higher-level fitness elements like strength, power, and speed. Physical therapist and author Gray Cook talks of mobility as the freedom of movement of multiple muscles and joints, then stability as “the ability to control force.”

As a coach, I’d be frustrated when given skier couldn’t grasp a certain aspect of technique, be it body lean angle (see accompanying photo) in skiing or lifting the knees when sprinting. But the athlete’s body won’t let them move that way due to mobility, stability or asymmetrical deficits.

For example, a restriction in ankle mobility will limit the amount of lean angle in running and skiing. Tight hip flexors/hamstrings or a weak core will limit the amount of pelvic rotation one can have or maintain (i.e. the butt pushing back).

Many of us have also coached athletes who are strong, but after many hours of work they did not develop to expectation. This, too, is a symptom of a mobility/stability deficit, as any higher-level development will not be optimized with an unstable foundation.

A simple system exists to evaluate and address this: the Functional Movement Screen. Many of us have heard of Cook’s book Athletic Body in Balance, a hidden gem in its implications for developing athletes by addressing these kinetic-chain imbalances. Once we diagnose and fix kinetic-chain deficits, like core instability, where an athlete has difficulty balancing on one leg, or stabilizing upper and lower body, we can progress athletes much faster.

From the time we are born, our body’s musculoskeletal and nervous systems start compensating and adapting to environmental stresses, such as repetitive movement, bad posture from sitting at a computer for hours a day, or injuring an ankle so we lose ankle mobility. The body mostly adapts in a positive manner, however as we mature our bodies are exposed to a host of repetitive stresses (and sometimes traumas) that can cumulatively cause restrictions/imbalances in our body’s movement, stability, and strength. This will cause inefficiencies in movement and power application.

With movement restrictions, no matter how hard we try, we cannot achieve an efficient body position. This compensated body position will not allow us to ski efficiently. This can be very frustrating to beginning and advanced skiers alike, and very perplexing to a coach. Why can’t this skier push his or her hips forward to get in a good body position? Why are they hunched or struggling with balance?

Coaches have skiers stretch, strengthen and do planks for minutes on end, yet problems persist. In order to more effectively address this, we need to think about, evaluate and train the musculoskeletal system as an interrelated system.

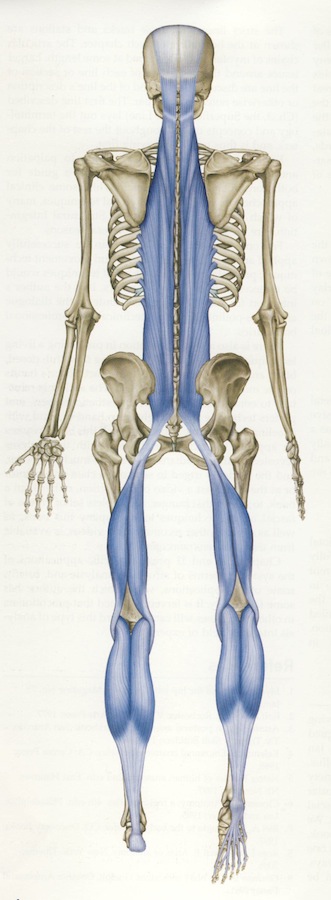

In the following model, refined by Cook and Thomas Myers, the muscles are thought of as a series of myofascial slings (a network of muscles) that extend the full length of the body. Hence what aches you have in your back can be driven by tightness in your foot or shoulder, as they are connected through the same muscular networks, or myofascial slings.

Your skeletal system works in tandem with this system. Its stacked joints alternate their roles between stability and mobility.

Michael Boyle explains this in depth in his article “The Joint-by-Joint Approach to Training.” The ankle is a mobile joint, knee a stable joint, hip is mobile, lumbar (lower) spine is stable, and Thoracic (middle) spine is mobile.

What usually happens if you lose ankle mobility due to multiple injuries or tight muscles? Movement has to happen somewhere so it gets transferred to an adjacent joint, usually the knee, which is meant to be a stable joint. The knee isn’t designed to be mobile so it gets sore or even much worse, injured (such as tearing an ACL, IT band, etc.).

Trying to fix a single problem, for example hip tightness or knee pain, will not be as effective as addressing the whole system. One muscle group does not work in isolation, nor should we train it in such a manner. In order to achieve proper body position when skiing, we first need to address movement restrictions to allow it to move freely and efficiently. Cook has taken this concept to a user-friendly level and developed a system of evaluation and corrective exercises.

For example, think about how many hours per day students and adults are seated. This seemingly benign activity will cause a variety of mobility and altered muscle firing pattern dysfunctions, such as tightened hip flexors and altered glute/hamstring functioning (glute amnesia).

How does this affect a skier? From running studies we know that for each degree of anterior hip rotation we gain 2 ½ centimeters of stride length. It is common with tight hip flexors to have a 5- to 10-degree deficit; think about the impact an improvement of this could have on one’s overall race pace.

In addition, if the glutes are turned off, the hamstrings are putting energy doing their neighbor’s job (and producing less power for locomotion), plus the knee is less stable and someone is going to be unhappy (i.e. knee or back pain, hamstring pulls).

As skiers, we strive for movement efficiency and optimal power production. To achieve this we need to evaluate skier’s mobility, stability and optimal muscle function. This is best achieved through an advanced Functional Movement Screen (FMS) or a very well done kinetic-chain physical therapy evaluation.

The basic FMS is excellent for picking up on major deficiencies, but well trained athletes have learned how to “cheat” very well. They need additional sub-tests to determine deficiencies, but this process has gained much-needed recognition and is used with many elite sports teams. The best option is to find a sports trainer or physical therapist who has a FMSII certification.

The athlete’s early season is an ideal time to have an evaluation done, this way corrective exercises can be applied in the preparatory phase of training and full movement restored prior to big summer volume phases.

So get all those muscles working together for better performance. Your body will thank you for it in the first races in the fall and winter!

Stuart Kremzner

Stuart Kremzner is an exercise physiologist, avid nordic skier and coach. He has a passion to help athletes develop to their fullest potential while gaining a love for the training process. When not working in his training center E3 Sports Performance he is out running or skiing on the trails with his family.