In the beginning of April, news hit that a group of athletes had tested positive for a banned steroid at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China. The group had never been investigated or suspended for doping.

The drug in question? Clenbuterol, a steroid. Its name might be familiar to cross-country skiers because it is often used in inhalers to treat asthma outside of the United States. But even for asthma, its use is prohibited for competitive athletes.

The positive findings for clenbuterol, which were present in samples from athletes of several nationalities and multiple different sports, included some from the Jamaican track and field team, according to Germany’s ARD television channel.

The findings were made in a 2016 re-testing scheme of the 2008 Olympic samples. They were never reported by the International Olympic Committee (IOC), and only brought to light by ARD many months later.

The IOC apparently decided that the traces of the drug in the urine samples were so small that they did not merit follow-up. The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) signed off on this decision.

One problem: like almost all of the drugs on WADA’s Prohibited List, there is no allowable minimum concentration of clenbuterol in a urine sample.

“Clenbuterol is a prohibited substance and there is no threshold under which this substance is not prohibited,” WADA writes on its own website in a Q&A about the Prohibited List. “At present, and based on expert opinions, there is no plan to introduce a threshold level for clenbuterol. It is possible that under certain circumstance the presence of a low level of clenbuterol in an athlete sample can be the result of food contamination… Under the World Anti-Doping Code, result management of cases foresees the opportunity for an athlete to explain how a prohibited substance entered his/her body.”

Explanations were apparently never solicited from the athletes in question, and the IOC simply buried the cases.

Scores of athletes have claimed in the past to have unintentionally ingested banned substances, arguing that the concentrations were so low that they couldn’t be performance-enhancing. It is an argument that has rarely been successful.

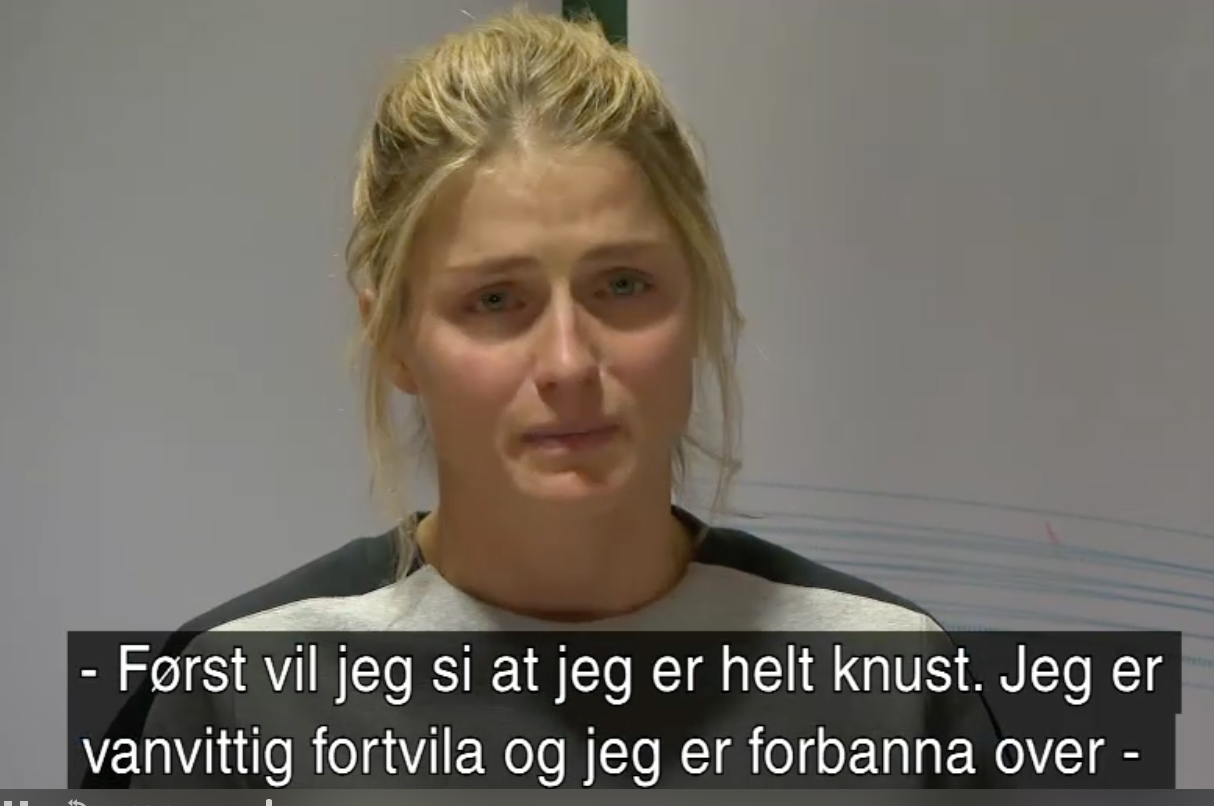

Among the athletes who were punished for unintentional ingestion are Norwegian skier Therese Johaug, who tested positive for clostebol, a steroid contained in a lip cream she used; and German biathlete Evi Sachenbacher-Stehle, whose tea was contaminated with the stimulant methylhexanamine – the same drug Carter was disqualified for – at the 2014 Olympics.

The Jamaican athletes in Beijing never went through the scrutiny that Johaug or Sachenbacher-Stehle did, and are unlikely, at this point, to ever serve penalties. Which begs the question: do the rules apply to everyone?

Or is it better to take a banned substance at the Olympics than at a training camp?

The Specter of Tainted Meat

There is no minimum concentration of clenbuterol allowable in the WADA Prohibited List. So the decision not to confirm the doping cases was not made in accordance within the workflow of anti-doping rules, but instead subjectively.

This is how it worked: ARD reported that IOC Medical Director Richard Budgett had instituted a policy that any positive analytical tests be cleared with him before being ‘confirmed’, the first step towards proceeding through the anti-doping investigation. These cases were reported to Budgett, and he said not to confirm them.

The normal procedure is that such positive analytical tests are considered violations and the athlete is given the opportunity to explain how the substance came to be in their body. They can argue that they ingested it accidentally, for example.

In this case, such an investigation and dialogue never took place. Because the cases were never ‘confirmed’, the IOC did not even confront the athletes.

According to the IOC, this was because of the risk of the drug entering an athlete’s body after they ate contaminated meat. The steroid is used to promote livestock growth in some countries, and China – the site of the 2008 Olympics – is one of them.

“It has been scientifically established that an athlete can test positive for clenbuterol at low levels following ingestion of contaminated meat,” WADA wrote in a press release after the documentary aired. “There have been hundreds of cases – limited to a number of countries where contamination is known to be an issue and where the athletes would have resided, trained and/or competed.”

Another athlete in Beijing – a Polish canoeist – tried to use contaminated meat as an explanation for why he tested positive for clenbuterol. In Adam Seroczyński’s case, the IOC didn’t buy it and punished him anyway.

“The behavior of the IOC is shameful,” a surprised Seroczyński told ARD after the news of the Jamaican tests came out. “They didn’t handle my case this way, I wasn’t as important.”

If the IOC had tried to conduct follow-up to establish whether contaminated meat was the most likely explanation for the positive tests, they may have been disappointed. Fearing exactly this situation, the Jamaican sprint team had flown its own meat to China from home, and their food was prepared by the team’s own cook, according to ARD.

After the fact, WADA explained their decisionmaking process.

“Effectively, when the circumstances of a positive case indicate that the athlete has been in one of the identified countries where clenbuterol meat contamination is significant, the anti-doping community views it as unreasonable to put the burden of proof on the athlete, i.e. to prove that the meat, which he or she had consumed, was contaminated; in particular, eight years after the fact,” the organization wrote in their press release. “However, before a case is closed on the basis of low clenbuterol levels consistent with contamination, WADA recommends investigating such things as meat intake and whether there was exposure to a geographical area where contaminated meat is known to be prevalent.”

As noted above, there does not seem to have been much investigation and this policy is directly at odds with WADA’s own policy as posted on its website.

Are Low Levels Really Accidents?

To justify the process, the IOC reported that in all of the 2008 clenbuterol cases which were not ‘confirmed’, the concentrations of the drug were below 1 nanogram per milliliter.

Other athletes have been banned for less; Spanish cyclist Alberto Contador lost his 2010 Tour de France title over a finding of just 0.05 nanograms per milliliter, despite also arguing that he had ingested contaminated meat.

In fact, in Contador’s case the Court of Arbitration for Sport wrote that “considering that clenbuterol is a non threshold prohibited substance, the fact that the concentration is extremely low does not have any effect on the result.”

And in the same ruling, the arbitrators ruled out that contaminated meat could possibly be a source for the drug. Noting that that Spain is not a country known to have a problem with clenbuterol contamination, they concluded that “no established facts that would elevate the possibility of meat contamination to an event that could have occurred on a balance of probabilities has been established.”

Thus, jurisprudence has established that concentrations of the drug can be found in very low concentrations in urine samples even where meat contamination is not a possible explanation.

Of course this makes sense: as a substance is metabolized, its concentration will decrease. The concentration in a sample is simply a product of the amount ingested, and time. A longer time since ingestion means a low concentration.

To get back to Therese Johaug: her urine sample, collected by Anti-Doping Norway, contained 13 nanograms of the steroid clostebol per milliliter. While that’s a lot higher than 1 nanogram of clenbuterol, it’s not particularly high.

In banning her for 13 months, the disciplinary panel did not dispute her explanation that the substance entered her body from a lip cream, rather than an injection or some other more shocking route.

The public will likely never know whether, in fact, she was using it on purpose; the accidental explanation has been used by many an athlete who later admits that yes, they were doping. But the point of strict liability actually gets exactly to that: it deals with the fact that when you rely on someone’s word, you can never be certain of what actually happened.

Strict liability is strict liability. WADA’s explanation of its Anti-Doping Code specifically notes that an athlete should be suspended “whether or not the athlete intentionally or unintentionally used a prohibited substance or was negligent or otherwise at fault.”

Part of the issue of the Russian doping scandal is that for athletes in some parts of the world, strict liability was being applied. But for some in Russia, it wasn’t just that unintentional positives were being forgiven – rather, intentional doping was protected.

In this new scandal, the IOC – which is charged with ensuring fair competition at the most prestigious sports events in the world, the Summer and Winter Olympics – strict liability only applies sometimes.

If you were an athlete working hard to stay clean, or even Therese Johaug or Evi Sachenbacher-Stehle, that must not feel great.

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.