In a split second, Katherine Stewart-Jones was flying over her handlebars and headed face-first for the road. She had been biking to her local gym in Thunder Bay, Ontario, on Sept. 19 when her bike’s front tire rammed into an irregular rise in the road and sent her off her bike seat and toward the unforgiving pavement below.

A person driving by witnessed Stewart-Jones catapult off her bike and stopped immediately to check if she was all right. Though the 22-year-old Quebec native had been wearing a helmet, her face had take the brunt of the impact, leaving her with two swollen lips and one very sore tooth. The passerby who had witnessed the fall stopped, loaded Stewart-Jones’s bike in the back of the car and ferried her the rest of her way to the gym.

When Stewart-Jones arrived at Thrive Strength and Wellness that day, Josh McGeown, who works as a strength instructor at Thrive, has a master’s of science in kinesiology and specializes in athlete injury and rehabilitation, took one look at her and informed her there would be no workout for her that day. In the gym’s office, McGeown immediately ran a few preliminary tests to decipher if Stewart-Jones had a concussion, though he also indicated it was, in all likelihood, too early to tell. She would have to wait for more symptoms to arise.

After McGeown’s prognosis, Stewart-Jones, a member of both the Canadian National U25 Team and National Team Development Center (NTDC) Thunder Bay, called the NTDC team’s doctor to arrange an appointment. She got in the same day as the accident, and a few more tests were run. Once again, however, she was told nothing could be confirmed until more signs of a concussion showed up. By the next morning, they did.

“I slept like 12 hours that night or something, not normal,” Stewart-Jones said on the phone in late November.

The morning following her accident, Stewart-Jones flew home to Chelsea, Quebec. She had been planning to return home to help with a Fast and Female event taking place in Ottawa, 10 kilometers south of her hometown. After the event, her plan was to fly to Park City, Utah, to join her fellow Canadian national-team members at a dryland altitude training camp.

But recurring headaches and the inability to do anything but sleep changed all that.

“I was sleeping like crazy,” Stewart-Jones said. “My eyes would get really tired. I had a lot of sensitivity to light and sounds, just being around people was like, ‘Whoa.’ ”

“I also ended up having some issues with my tooth,” Stewart-Jones explained. “We weren’t sure at first if it was injured, but it ended up changing colors, like turning purple. So I ended up having to get a root canal.”

Besides a tooth that necessitated endodontic treatment, Stewart-Jones’s accident also left her with no energy to train, despite wanting to do so. For close to a month, she rested, unable to train or complete any of the online psychology courses she was taking at Lakehead University. Even reading screens bothered both her eyes and her head.

For Stewart-Jones, the hardest part of coping with the injury was transitioning from full-time training to barely moving.

This sentiment surfaced in Stewart-Jones’s blog post following the accident, where she reflected, “I think we can all agree that cross-country skiing is one of the hardest sports in the world. I have been training for skiing for as long as I can remember, but these past six weeks have been the toughest of my career and I have barely lifted a finger.”

“When you’re used to doing so much and then not being able to do much at all was just frustrating and then also just kind of depressing,” Stewart-Jones later told FasterSkier. “I spent a lot of time feeling almost sad and really sorry for myself.”

Couch-ridden in Chelsea, while her teammates and the rest of the cross-country world continued to train, Stewart-Jones was faced with the question any athlete who has put endless amounts of time into a season and suffers an injury dreads: was it all for nothing?

“I definitely had that thought of, is my season over?” she said. “Kind of that panicked moment where it’s like this is an Olympic year and I want to qualify for the Olympics and I kind of felt like maybe my dream is crushed.”

But that was one question she wasn’t going to wait around to find out. She began a proactive approach to recovery, which included logging her symptoms and journaling, guided meditation, and staying in contact with therapists, chiropractors, acupuncturists, and teammates (read more about the five steps she took on her blog).

She remained in contact with McGeown, who’s master’s research project at Lakehead addressed how to help athletes safely return to sport post-concussion. The two emailed and texted regularly while Stewart-Jones was at home in Chelsea, with McGeown offering advice and suggestions on how to cope with the mental and physical side affects from both a professional and personal standpoint.

A former rugby player, downhill skier and contact-sports enthusiast, McGeown himself has suffered more than 15 concussions during his athletic career. On the phone with FasterSkier, he recalled his own undergrad experience when the solution for the concussed was to “sit in a dark room and hope you get better.”

“At that point in time, there was no advice from doctors or physios,” said McGeown, who will start working toward a doctorate at New Zealand’s Auckland University of Technology this year. “It was, if you have any symptoms at rest, don’t exercise. For up to a year, don’t workout, don’t go for runs, don’t lift weights, don’t play sports. Essentially don’t do anything you like to do.”

However, recent research done by McGeown and acclaimed medical sources, such as the Journal of the American Medical Association, have changed that belief. While all rest and no play was formerly viewed as the most appropriate way to recover from a concussion, recent studies show the opposite. Exercise appears to be the preferred method of rehabbing a concussed individual, though the intensity, duration and type still vary case by case and remain in question.

“They release new guidelines every four years,” McGeown explained. “The 2012 guidelines say rest; do nothing. The 2016 guidelines say exercise-based rehab is going to be the new cornerstone for concussion rehab. They’re not saying how often, how intense, how do you get them started, for how long, etc. What the research needs to figure out still is all those variables. What is the best case scenario or is it completely individualized?”

In the case of Stewart-Jones, slow and steady was the start. At home in Chelsea, she began exercising once she had a full 24-hour period of no symptoms. Following the 24-hour period, she completed ten minutes of exercise (in her case, walking on the treadmill) at a heart rate of 115.

If, after completing the workout, no new symptoms arose or worsened, she would either increase her time or her heart rate the following day, but not by much. If her symptoms worsened or new ones arose, she returned to the exercise she had been doing the previous day — no exceptions and no matter how badly she wanted to train more.

“Everybody wants to be tough. Everybody wants to fight through it and push through it,” McGeown said. “But what I try to get people to conceptualize is, if it’s your ankle or knee or shoulder, go for it. Tough it out, because when you’re fifty or sixty and that knee is really bothering you, they’ll just replace it with a new one.

“Whereas there’s no second chances with our brain,” McGeown continued. “We’re seeing that with football players and hockey players. There are extreme consequences and if we don’t take it seriously, it’s a big deal.”

Even with that weighing in the back of her mind, Stewart-Jones still found it difficult to not rush back into training too quickly.

“I found that one of the most difficult parts of recovery was knowing when I was feeling good enough to start training again,” Stewart Jones wrote in her blog. “I found it easy to convince myself that I was feeling normal when I wasn’t. Maybe it was because I was just too eager to get back to training or maybe it was because I truly couldn’t remember how it felt to be my normal self. The bottom line is, you know yourself best, so be honest with yourself, and the recovery will be much quicker.”

When she returned to Thunder Bay a few weeks after her accident, she began working with McGeown in person, continuing her work on the treadmill until she had reached the point where she was exercising at a threshold pace, something similar to a steady state.

After that, McGeown began a second phase of the recovery, adding higher intensity workouts to her training regimen. She would complete 30-second long speed bursts of mountain climbers, ski erging and box jumps followed by a check-in with McGeown. If all went well, she continued. After about ten sessions like this, Stewart-Jones was cleared by McGeown to return to normal training.

In late November, a little less than eight weeks after she suffered her concussion, Stewart-Jones was back on skis, logging a 17-hour training week and feeling “100 percent.”

“Initially I was supposed to leave on Nov. 11th to meet the team in Finland and race the Ruka [Triple],” Stewart-Jones, last year’s NorAm (Canada’s Continental Cup) winner, said of her plans to start her season on the World Cup for Period 1. “I was feeling fine, I didn’t have any symptoms and I could train fine, but I felt like I wasn’t going to be ready enough to race then. And I wanted to put a couple weeks of big volume in just to feel like I gained my fitness back, so [my coach Timo Puiras and I] made the decision to stay longer.”

“Katherine’s summer training went very well,” Puiras, head coach of the NTDC, wrote in an email. “Our IST (Integrated Support Team) was excellent in getting Katherine back to normal training as quickly as possible.”

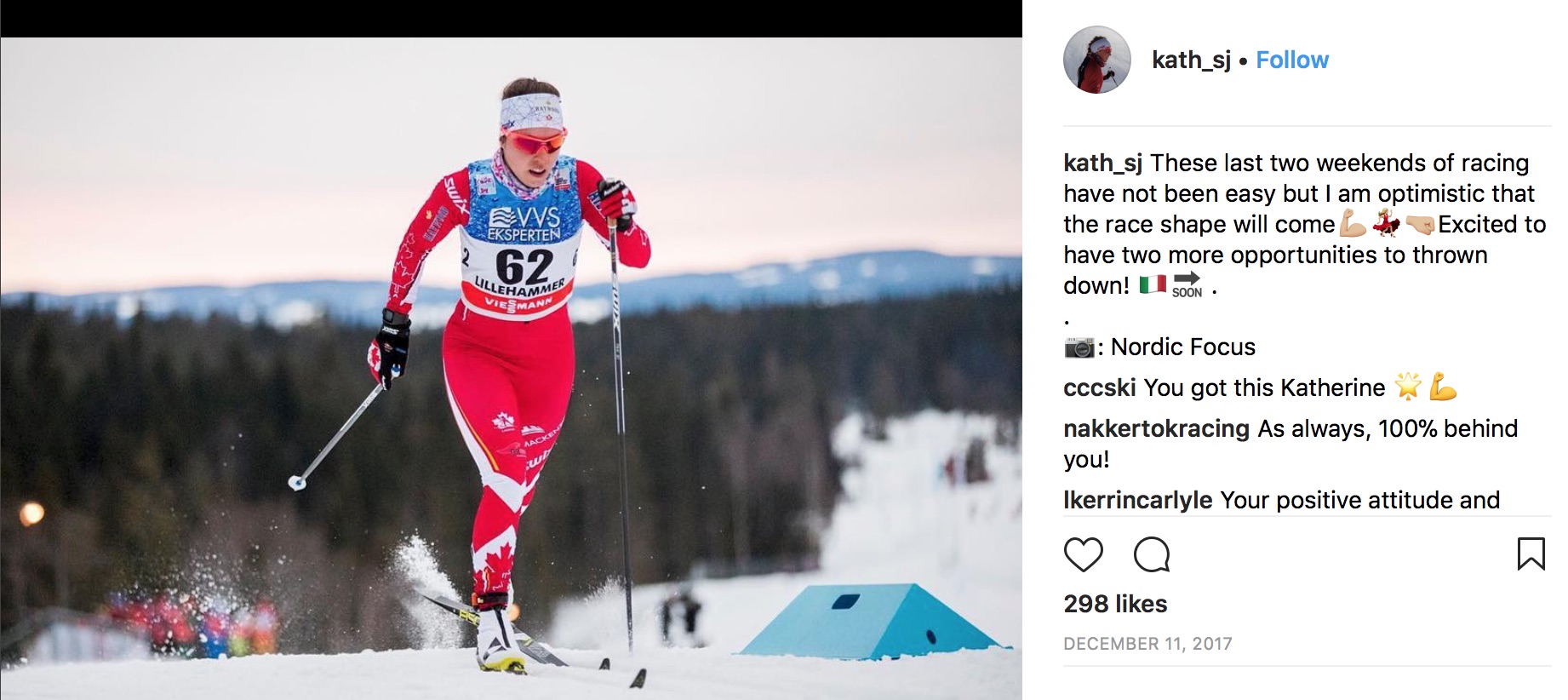

She competed in three World Cup weekends so far this season, posting a best result of 55th in the freestyle-sprint qualifier on Dec. 9 in Davos, Switzerland. She’s now gearing up for the NorAm trials, which start this Friday in Mont Sainte-Anne, Quebec, where she and several other top Canadian skiers are hoping to earn a spot on Canada’s Olympic team.

“It was definitely a lot after taking a good six weeks off for an injury,” Stewart-Jones told FasterSkier after the Davos 10 k freestyle on Dec. 10. “I’ve had a good month of training, but it was more volume focused, just because I wanted to gain back that fitness and so I didn’t do a lot of intensity so I was kind of expecting it to be rough. But having the NorAm leader’s spot, it wasn’t something I was ever going to turn down.

“I think for distance racing I still have that extra gear to build,” she added. “Right now I feel like my technique has come a long way, but I don’t feel like I’m actually racing, and I think that’s just going to come with more intensity and more racing.”

When asked if Stewart-Jones might be at a higher risk for concussion while competing on the World Cup now, McGeown explained it would be difficult to say without know her particular history with concussions.

“Once you’ve had multiple concussions, it’s easier to get the next one, the symptoms are worse, and recovery takes you longer,” McGeown said. “But typically if someone’s at a high risk for reinjury, it’s going to be if they return to sport within that first week to two weeks after the initial injury. It is certainly possible it could happen again, but it could happen to anyone at anytime.

“That she’s at a high risk, I would say no. She’s at the same risk as any other skier competing against her,” McGeown added. “The only way that a concussion is going to truly limit someone is if they let it.”

— Chelsea Little and Alex Kochon contributed

- concussion recovery

- concussions

- Davos skate sprint

- Davos World Cup skate sprint

- Josh McGeown

- Journal of American Medical Association

- Katherine Stewart-Jones

- Lakehead University

- mont sainte-anne

- Mont Sainte-Anne NorAm trials

- MSA NorAm trials

- National Ski Team

- NTDC Thunder Bay

- Ruka Triple

- Thrive Strength and Wellness

- Thunder Bay

- timo puiras

Gabby Naranja

Gabby Naranja considers herself a true Mainer, having grown up in the northern most part of the state playing hockey and roofing houses with her five brothers. She graduated from Bates College where she ran cross-country, track, and nordic skied. She spent this past winter in Europe and is currently in Montana enjoying all that the U.S. northwest has to offer.