LAUSANNE, Switzerland— After presentations and question and answer sessions yesterday at the Olympic Museum, today was the Almaty and Beijing 2022 bid committee’s last chance to officially sell their Games proposals to International Olympic Committee (IOC) members and the media in person.

Situated at the Lausanne Palace Hotel, a swanky venue where a room costs well over 400 Swiss Francs – roughly equivalent to United States dollars – and a simple coffee 5.50, IOC members discussed the options with organizers and the press.

The bid committees also put together presentation rooms to showcase their bid concepts. Think part World’s Fair, part hospitality tent, all salesmanship.

IOC members who are not part of the Evaluation Commission are not allowed to visit bid cities in person to help make their decision about which to vote for.

The idea was to prevent corruption, and not allow cities to spend huge budgets on coddling the voters during their visits or lavishing them with gifts in order to buy loyalty.

Some regulation was a good idea, because that strategy obviously works. The rule was made after the 2002 Salt Lake City scandal where the organizing committee bribed IOC members for votes. Bribery and special treatment are also a key part of the recent scandal at FIFA, the international governing body for soccer.

IOC members are uncompensated for their time with the organization. President Bach only recently received a salary for the first time, although he is also given residence in Lausanne by the organization, at fairly great expense.

Instead of salaries, members enjoy many other perks of their status. When citizens in Oslo voted to not bid on the 2022 Games after a bid committee put together fairly extensive plans, demands by the IOC were cited as one of the reasons that they would not want to be associated with hosting the Games.

For instance, there were reportedly requests for IOC members to have separate entrances and exits from the airport, separate lanes on roads for travel, and to be provided with brand-name mobile phones and country-specific calling plans by the organizing committee. (A longer list of the demands, and reactions to those demands, was tallied by Inside The Games.)

Of course, that was at the Games, rather than during the candidacy process. But one can imagine that the same sort of benefits would be much appreciated by voters.

So instead of allowing in-person treatment of this sort to bias voters, the new rules only allow lobbying on neutral ground, in this case Lausanne. The 2022 Games bidding process will be a test to see whether the new concept works. Both bids are seen as having problems, for instance air quality and environmental human rights issues.

Some concerns are addressed in the Evaluation Commission packet, but at 137 pages in length, it is acknowledged that many members may not read the full details.

The challenges are glossed over in bid packets that contain the most accessible, quotable information that voters and journalists have; in one press conference, a member of the Beijing bid committee said, “Air quality is considered good. You can find relevant numerical data online.”

But who wants to go online and search through dense, perhaps difficult-to-interpret data on air quality, when ready-made statements are right there in the media packet?

In the Beijing 2022 Candidate City kit, right there on page three is the “Vision” statement.

“As an Olympic celebration upon ice and snow, the Beijing 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games will offer a pure and clean environment for sport, ecology, and culture…”

This seems unlikely, but it has not been possible for IOC members to visit Beijing in person and see whether reality matches the glossy statements by the bid committee. Breathing the air themselves, for instance, would give a good idea about whether it’s ethical to ask athletes to breathe it during competition.

In fact, few people have been able to even see the area that is slated to host venues for alpine skiing. On a press junket as part of the evaluation package, the few foreign journalists invited begged to at least be able to see the Yanqing site where the alpine and sliding venues will be built. Instead, they were treated with a trip to a winery.

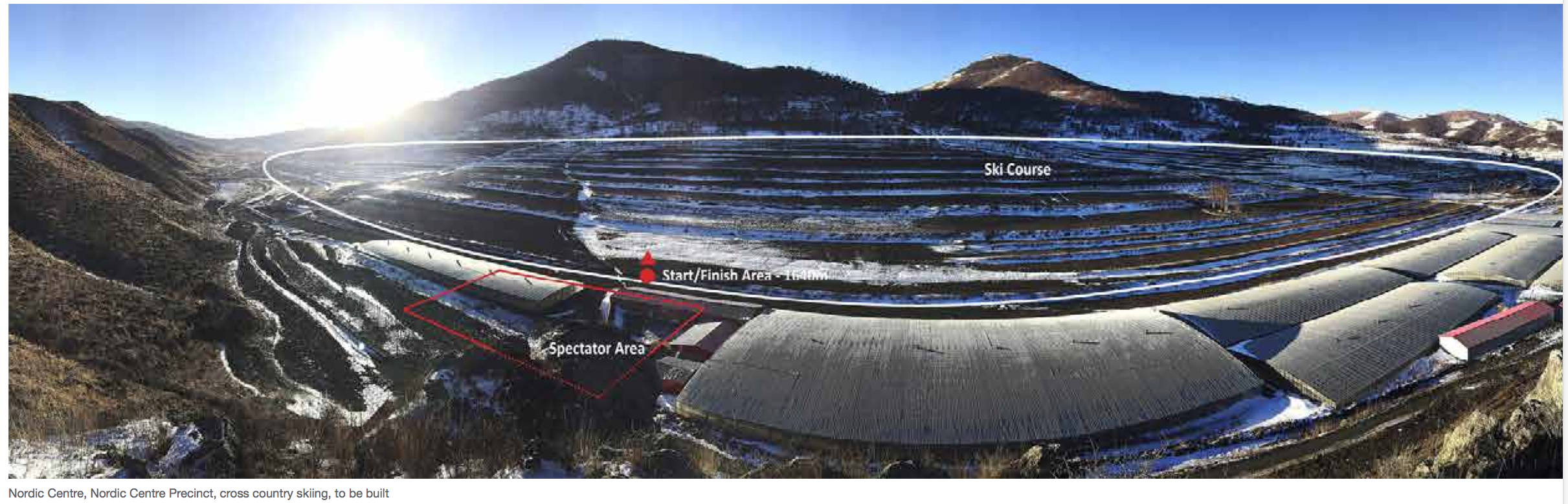

The Zhiangjiakou site, which will hold freestyle skiing, snowboarding, and nordic disciplines, was open. But venues were not built yet and at the existing small ski resort, slopes were brown. What would the Yanqing site have looked like, if they had been allowed to see it?

It’s easy to pick on Beijing, but it’s not any easier for IOC members to assess the Almaty bid, either. At least many IOC members have been to Beijing – most were there for the duration of the 2008 summer Olympics.

In fact, that is seen as a major disadvantage for the Almaty bid. Instead of leveling the playing field, the new rule seems to have created a built-in inequality: Beijing has had Olympic exposure, and Almaty has not.

Because finally, the decision will not only come down to evaluating the challenges and risks associated with each bid. It will also depend on how IOC members access the positive aspects.

What will the Games atmosphere be? How are the venues, and what will they feel like when they are filled with cheering fans? Will it be a good experience for all? Are the locals receptive to the legacy of sports that each bid committee insists it is building?

To answer these questions and make their decision, IOC members must rely on lines from press shills, information in blandly-written reports or overly-positive promotional materials, and finally, the presentation rooms.

For a taste of what that means, here’s a look inside those rooms.

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.