(The following op-ed is an opinion piece submitted by an author unassociated with FasterSkier. Viewpoints do not necessarily reflect that of FasterSkier’s staff or sponsors. We fully support open dialogue and encourage the use of the comments section at the bottom of this page to express varying views. To submit an op-ed, email info@fasterskier.com.)

About the author: Kris Freeman raced for the U.S. Ski Team for more than a decade, from 2002 to 2013. A four-time Olympian who placed fourth in the 15 k classic at both 2003 and 2009 World Championships, Freeman, 36, is currently training in New Hampshire in hopes of making the 2018 Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea.

***

“The U.S. Ski Team will select only the most qualified athletes with the greatest possibilities for winning medals in future World Championship and Olympic Winter Games competitions,” the team wrote in its 2018 national team selection criteria.

In a recent interview, Head Coach Chris Grover explained that the potential for winning medals was key to several discretionary nominations.

I believe that there should always be room for discretion when nominating athletes, but the vague “medal potential” standard has become an excuse for the national team coaches to have free reign.

It’s another example of how the U.S. Ski Team markets itself to the ski community as all-inclusive, as representing all of U.S. skiing. But watching their actions, this advertisement rings false.

Can the best skiers make the national team?

Before I go any further, I believe that a case can be made for every athlete nominated for the 2017/2018 team and I mean no disrespect to any of them.

I merely wonder how many skiers in our country are consistently overlooked and what part personal favoritism plays in the nomination process.

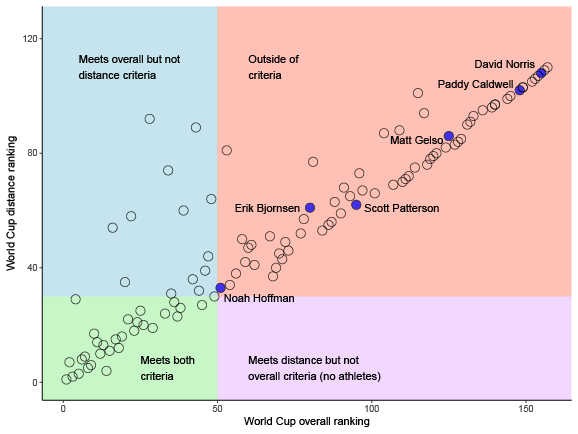

For the first time in several years, the B-team is made up entirely of discretionary picks. Noah Hoffman failed to make the objective criteria by only one World Cup point but was left off the team. Yet Erik Bjornsen scored 66 fewer points than Noah and was still named to the team for the fifth time.

It should be noted that Erik has never made the objective criteria in any year, and also did not objectively qualify for this year’s World Championships in Lahti, Finland, based on written criteria.

Erik teamed up with Simi Hamilton to take fifth place in the team sprint and was 18th in the 15 k classic in Lahti. Even though success at World Championships is ostensibly one of the national-team’s main goals, those solid results were not sufficient for an objective nomination.

I believe Erik is our best all-around skier and, again, I have no issue with his nomination. However, when the best skier in the country can’t make the B-team criteria, it raises questions.

I believe the unstated rationale for the high objective standard is that ski team leadership wants complete control over the nomination process. The easiest way to do that is to put objective criteria out of reach, keeping athletes on the B-team in a constant state of subservience as the team’s decisionmakers hold the keys to their livelihood. The team can tell them what to say to media and what financial information can be disclosed to the public.

Ask yourself: when was the last time a U.S. Ski Team athlete talked publicly about a poor wax job? Are you aware that B-team athletes have to pay roughly $150 each day that they are in Europe racing on the World Cup? Have any of them ever mentioned that in an interview you have read?

Who scores points?

The particular results, numbers, and details of individual nominated-or-not cases (see “More Discretionary Picks” below) are interesting fodder and could be discussed for hours. But doing so might miss the forest for the trees. Such decisions are emblematic of broader problems at the U.S. Ski Team.

There is no written standard for athletes to qualify for the funded A-team vs. the unfunded B-team, but the common discretionary standard that the U.S. Ski Team has used is a top 30 ranking in either Distance or Sprint world ranking list, formerly known as the Red Group.

The team used this standard because Red Group skiers were partially funded by FIS up until this year. But now that the FIS funding allocation system has changed, maintaining this standard merely encourages our athletes to start every World Cup in order to not miss a chance to score points. For an organization that claims World Championships and Olympic medals are their only goal, racing their own athletes into the ground is hypocritical.

Paddy Caldwell and Scott Patterson were also named to the B-team using discretion. Paddy followed the pipeline route to his nomination. With two top-10’s at U23 World Championships, his nomination at some level was predictable even if he did not meet objective criteria.

Scott’s nomination is more of a mystery. He is too old for the ski team’s pipeline system, and he wasn’t nominated to the World Championship team. He did have some solid World Cup results, taking ninth place on the Olympic trails in South Korea and 27th at the Holmenkollen 50 k in Oslo. However, it should be noted that Noah beat him in Korea in his last race of the season before he came down with pneumonia.

The World Cup start rights that were given to Patterson baffled the rest of the domestic field, as there was no qualification criteria for them or explanation for why those starts were granted; in a recent interview, Grover told FasterSkier that “We wanted to find opportunities for Scott.” Scott definitely did well with these opportunities, but who is to say that other domestic skiers could not have had the same success?

Then there is Tad Elliott, who was the king of clutch this season. As a distance skate specialist, he took third and second in the two freestyle World Championships qualifying races. Then he went to Finland and pounded out a 27th place finish in the 50 k, the best result we have had in that race since I was 12th a decade ago. As a reward, Tad was snubbed for World Cup start rights at World Cup Finals in Quebec. The disparity between Scott and Tad’s treatment is troubling.

Meanwhile, Rosie Brennan is the only women’s B-team nominee this year despite Caitlin Patterson having scored an identical amount of World Cup points and Chelsea Holmes putting up a 13th place in the 30 k skate at World Championships. Rosie may, as Grover says, be a medal contender in the 4 x 5 relay. But by that rationale, Caitlin and Chelsea should also certainly be named to the national team.

Crucially, the standard also makes no sense in that it does not differentiate success against strong fields versus weaker ones. For instance, Liz Stephen scored 98 of her World Cup points en route to a second place finish in the Korean World Cup. The race had the weakest World Cup field in my lifetime. Liz scored most of the rest of her points in the hill climb in the Tour de Ski. Only 31 women started, and last time I checked, there are no hill climbs in the Olympics.

I want to reiterate that all of the athletes nominated to the team deserve to be there. Liz is clearly one of our best skiers.

But all the same, why is a non-championship event being used as a standard to make the U.S. Ski Team, whose primary stated goal is to win medals?

The Tour de Ski ended up being a points feeding frenzy. Rosie Brennan and Liz would not have qualified for the World Championships without it. They did not accrue enough points to make the top-50 standard until that final Tour stage. Noah also qualified for the World Championships in a non-Championship event on the final day of the Tour against a diminished field. Is racing up a hill at the end of a nine-day tour really a fair way to determine who goes to the World Championships or Olympics?

Even if you believe that the Tour de Ski is a fine qualification basis for the Olympics, there is that access problem. U.S. Ski Team staff can (and does) give or deny Tour de Ski start rights at their whim. There are no written standards for how these spots are doled out. I believe that there are half a dozen domestic skiers that potentially could have qualified for the World Championships had they been given the opportunity to race World Cups during the qualification period.

What are the priorities?

The U.S. Ski Team has gradually consolidated too much power in the naming of the national team, major Championships teams, and World Cup start rights. “Discretion” and “medal potential” are getting in the way of U.S. cross-country skiing reaching its true potential. The team’s World Cup staff need to have a presence at Nationals and SuperTour Finals, so that they have a hands-on way of evaluating domestic talent.

This brings me to the most aggravating part of the U.S. Ski Team dynamic in relation to domestic skiing. I call it “teaminess.”

Much has been made of the good team dynamics that the women’s team has marketed, and clearly it is working for them. However, the staff uses these dynamics as another way of controlling team composition: they have decided what emotional attributes an athlete should have, and if the athlete doesn’t have them (or doesn’t pretend to have them) he or she is not welcome.

“Attitude and commitment of athletes” is even one of the discretionary criteria for team selection.

This could be construed to include every male athlete in the country because it is well-documented that men and women have very different psychological needs. As a generalization, women perform better when they train in close-knit groups amid lots of social support. Men, on the other hand, generally like to have independence and thrive when given space and respect.

Yet for the last six years, the men have been perpetually bombarded with criticism for not behaving like the women’s team. Many independent-minded skiers, who have posted some of the best results in our nation’s history, do not feel supported or welcome within the U.S. Ski Team structure.

My question is, how real is the team dynamic if it is so fragile that it could collapse by the mere presence of these skiers?

Also, is it fair to protect the women’s team from any type of intrusion at the expense of the men’s team and anyone on an ever-expanding blacklist?

The staff appears to believe that it is. In the name of maintaining the status quo, the team has avoided hiring a men’s coach, perhaps due to a desire to not disrupt the women’s team dynamic.

It is completely unacceptable that the men’s team has no dedicated advocate among the staff of the governing body.

What are we paying for?

The “teaminess” factor also plays into financial issues. The U.S. Ski Team wants to be all-inclusive when it comes to raising money from the cross-country ski community and projects itself as a supportive and welcoming resource. But in reality, the team’s resources are denied to many athletes with the potential to succeed internationally.

With the current lack of funding coming from U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association (USSA), the nordic program could not survive without assistance from the nation’s clubs. In return for this financial support, the clubs should know how their money is being spent. And there should be clear, attainable objective criteria for their striving athletes.

But what is the budget of the U.S. Ski Team, anyway? It has been a decade since anyone at the USSA released a cross-country skiing budget document to the public or press. Most years, they won’t even answer what the overall budget cost is, without even getting into how it is broken down. That’s quite the culture of secrecy.

The U.S. Ski Team coaching staff has become convinced that only they know which athletes should be supported – and how they should be supported. They have created a closed system over which they have complete control.

This is a fearful and exploitative way of running a national governing body. U.S. skiing will not grow without outside ideas and influence.

It is time for leadership that is open to all personalities and ideas. Fear of losing what we have will not allow us to reach our true potential as a nation.