My VIP was slow and deliberate, but in control. “Okay Joanne,” I directed her, “This is a grade 1 downhill, flat camber with a slight curve to the left part way down. Move forward and then get into a snowplow.”

Following her down, I called out “Ski left” as the trail curved. “OK, now straighten out”. She reached the end of the ramp without incident, but I needed to make sure she stopped before getting to a cluster of skiers chatting. “Snowplow to a stop; you are down. Nicely executed, Joanne!”

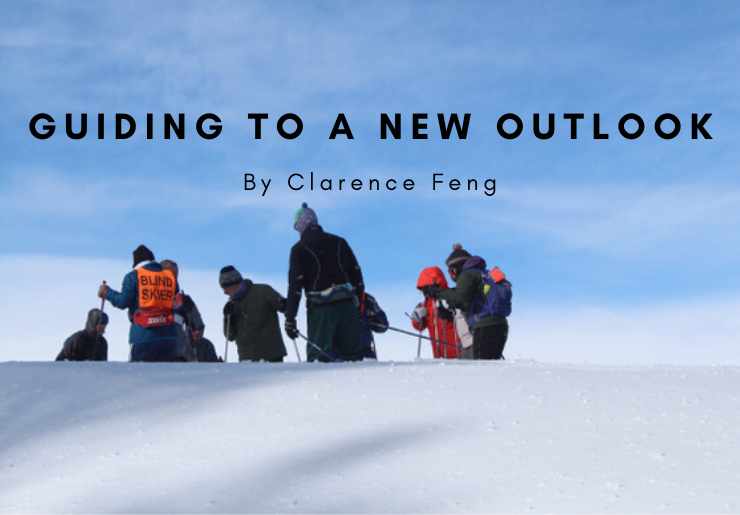

Two ski seasons ago, I began guiding for the New England Regional Ski for Light (NERSFL), one of several organizations in North America dedicated to teaching visually impaired participants (VIPs) to classic ski. Their extended weekend events combine outdoor experience with social gathering. .

I had signed up for guiding out of curiosity, and it turned out to be much more rewarding than I had expected. Guiding visually impaired people was definitely a change from my usual mode of skiing — striding solo through the woods — but it made sense given how my attitudes had evolved over time.

After a long time muddling about as a recreational skier, I decided about a decade ago to become a ‘student of the sport’, attending masters ski camps, watching videos, and reading books on training. I started to pattern some of my off-season exercise to be more specific. After all, ‘skiers are made in summer’.

Clicking through training articles and videos, I noticed I was only seeing white people. As a Chinese American, this didn’t come as a total surprise. Outdoor life, and skiing in particular, centers on the experience of Caucasians. Because skiing was primarily a solo activity for me, I had been able to overlook the lack of diversity I saw on the trail, but the absence of people of color online as well made me curious.

I wanted to know: who else is out there?

A search for ‘nontraditional’ cross-country skiers led me to Ski for Light and the separate regional organizations. Collectively they share a mission to provide partnering and a ‘safe space’ for skiers with a visual or mobility impairment. I was attracted to their goal of broadening access to the sport I love. As an American whose physical appearance regularly triggers an assumption that I’m a foreigner, I sympathize with others perceived to be outside the norm.

I had another reason for getting involved. My father lost his eyesight to macular degeneration and retinal detachment. Undergoing my own emergency retinal surgery brought home how real those risks were. My vision was fully restored, but I became concerned about the future, and wondered what skiing might be like without sight.

Before I was allowed to participate as a guide, I studied the SFL manual which described partnering and trail protocol in detail. The manual familiarized me with the verbal commands and cues to safely guide a participant, or ‘VIP’. My first weekend event with Ski for Light was relatively seamless. Pairs of participants and their guides were grouped into teams and all teams had at least one radio. The touring center set double-tracked trails to conform with SFL trail protocol. Each day was planned the evening before, with a morning briefing before heading out.

As part of training during my first weekend, I was paired with another new guide and we each took a turn playing participant while blindfolded. Striding in good tracks without being able to see was new and different. The first challenge was ‘proprioceptive’: learning to depend on the internal sensation of body movement and orientation. I also became alert to making small adjustments in stride by feeling the tips of my skis scrape against the sides of the tracks. Even with helpful verbal cues from my guide, I found the hardest transitions came where a downhill flattened out, and my body would lurch forward before I was ready.

On my first outing as a guide I accompanied my partner to the trailhead. I helped position her skis and gave verbal assistance so she could clip into the bindings on her own. Along with other pairs comprising our team, we headed onto a network of easy trails in a woodland surrounding a stream.

Observing the group, I noticed how quietly some participants moved their bodies. They didn’t gesticulate or wave their arms around while skiing: no flailing or sudden moves. It appeared self-protective in a way I could relate to. I admired their determination and willingness to commit on command to direction from guides.

When I wasn’t guiding, I needed to learn how to mingle with groups of participants and offer assistance. Always introduce yourself. Ask, don’t assume they need assistance. Offer an elbow to take when walking. They were sanguine about my newbie mistakes and the number of times I called ‘watch out’ without describing the what or where.

Trust is key, I was told by Susan Bueti Hill, President of NERSFL, an avid skier who is legally blind. Participants need to have trust in their guides. Guides in turn have to be focused on the safety and enjoyment of their partner. Part of the fun is giving them an opportunity to test their abilities and desire for thrill. Groomed trails are an important feature because fresh, firm tracks enable blind skiers to take a bolder stride, making every change in direction or momentum a small and controlled adventure.

One afternoon I guided a young man from Virginia who was preparing to go out west for a week-long Ski for Light event. Like any vigorous skier, he wasn’t afraid to expend some energy. I had him double-pole along flat sections and jog his way up the shorter rises. Johannes Høsflot Klæbo might not have anything to worry about, but I was glad he asked to stop at the activity center afterward to get details about his skis and boots.

Over the course of two winters, I found the participants at Ski for Light were just as eager to get out and ski as I was, maybe more so. No matter how unpromising the weather (notoriously variable in New England), they never flinched. Raining? Get skiing done before the tracks melt. Glazed surface? As long tracks were there, they were good to go.

On the final day of my most recent NERSFL weekend, the rest of the group departed for home just after lunch. I had arranged to stay one extra night, so I had the afternoon free. It was sunny and warm, a beautiful spring skiing day, and I was glad to get out and ski on my own. Partway up the trail I scored a bottle of sports drink from a feed station set up for a citizen race that had just ended. Reaching the yurt that marked my turnaround point, I reversed and began double-poling back down the soft, wet tracks. Back at the trailhead I found a bench in the sun and stretched out.

Skiing with SFL allowed me to use what I knew about skiing in a new way. Guiding made me observe another person so closely it became an empathetic experience, sharing that primal pleasure and thrill in gliding over snow. I also learned something about lowering barriers to skiing for the visually impaired. The people I guided may not have been able to see, but I hoped they felt seen by me.

It was now late afternoon and sunlight slanted across snow-covered fields. As I eased off the bench and took up my skis I checked the sun’s angle above the horizon. Just enough time to get beer and pizza before darkness fell.

If you want to know more about Ski for Light in North America, start at https://www.sfl.org, where there are also links to individual regional organizations across the US and Canada.

Clarence Feng is a skier based out of New York. You can find more of his writing and musings at Across the Snow Line – Dispatches about Nordic Skiing near NYC.