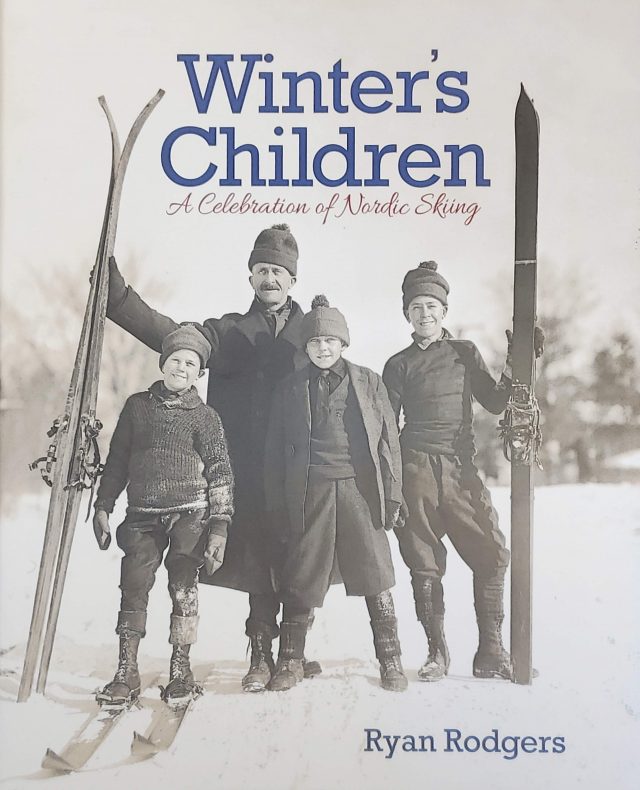

In a history of American skiing centered around the Upper Midwest, author Ryan Rodgers weaves together the stories of individuals who have found joy, love, and purpose in skiing with their heel detached, inspiring his readers to do so, too.

At the intersection of outdoors and pursuits, the street signs read “myth” and “heroes.” And we, those who spend our time outside, are here to patiently listen.

That intersection has given rise to classics across the myriad of ways humans interact with various natural playgrounds. Surfing has the permanent nostalgia laced in Endless Summer, rock climbing has the steady, emotive death-defying of Free Solo, and alpine skiing has the entire catalog of Warren Miller. These submissions to the genre are appropriate for their outdoor pursuits: flash-in-the-pan instances of action, bringing together visual and audio media to make something that’s brilliant.

But also, brilliance that’s just, well, oh-so accessible.

For cross country skiing? The individualistic and energy intensive mode of moving through winter’s harsh environment on skis requires a medium suggestive of walking its lonesome valley, and the ancient timelessness of doing so. It’s perhaps less glamorous than climbing nearly 3000 vertical feet up a cliff face with no rope, but also easier to connect with; less documentary, and more rhapsody.

With “Winter’s Children: A Celebration of Nordic Skiing,” Ryan Rodgers has accomplished just that. His work is a well-researched, extensively reported history that gets at the Norwegian ideal, sought throughout, of idraet – ski-sport, the mixing of ancient technique with spiritual renewal. Rodgers takes the epic tales of American skiing, and allows its practitioners to work together with his prose to form a journey with all the ebbs, flows, wanderings and epiphanies of a long ski in the woods. In doing so, he lifts the stories of this sport, done at the edges of frozen existence, out of the ether and into something material.

Rogers himself quickly sets the limits of what his project is from the outset; this is ostensibly the story of skiing centered around the Midwest. Not, as he says “a comprehensive look at the almost unfathomably long history of Nordic skiing,” but instead, “a celebration of an often-intertwined array of people and places.” In other words, he is out to tell a folk-history.

In doing so, Rodgers’ focus lies primarily on the folks in that history, interweaving the individual stories of people – some well known to the world, some well known to the Nordic community, and some simply not well known at all – who found the crevices and creases of human life using a pair of free-heeled skis as a medium. This is a work about skiing, yes, but also one in which the storytelling lets tales of freedom, fraternity, courage, and humor shine through.

I highlight this strength first because it gets to the heart of who should read this book. That is, although this is a Midwestern-centric skiing history, the bounds of that history include people and places that will be of interest to skiers from all over. Yes, the narrative, especially when skiing first hits America in the late 19th century, returns again and again to figures that touched the Midwest, but that is only a consequence of accurate historiography.

That is clear from the outset here. The first figure that Rodgers illuminates is Sondre Norheim, so-regarded as the father of modern skiing in his native Norway that both times the country has hosted the Winter Olympics (Olso in 1952, Lillehammer in 1994) the torch relay has begun with a flame from his hearth in Morgedal, Telemark. He is a national hero. And yet, he lived most of his life in Minnesota and died in North Dakota. The intercontinental connection is a common theme for most of the early history of skiing in the United States. Nordic Skiing was the great cultural product exchanged between those Scandinavians who came to America, with its port of entry the Twin Cities, farm fields of Wisconsin, and mining camps of the Iron Range.

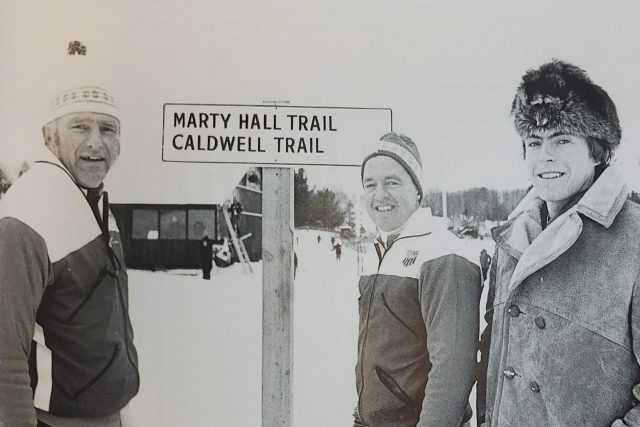

From Norheim, Winter’s Children begins to layer in the stories of the types of names that most of us skiers have come across in the name of a memorial race, or on a trophy or trail system. Rodger’s strength, especially in the early days of American skiing, is being precise in which characters he fully fleshes out, and then jutting and jiving between their narratives to interweave the particular pressures of a period on racers, organizers, and promoters alike. Then, like seeing a technical downhill off-shooting from a flat ski trail, he is willing to make us stop, turn at full speed, and take off to complexity and joy in his storytelling.

That’s how tales that for many skiers may have been whispers and vague allusions brought up at their local ski chalet become full-on stories – rising action, climax, denouement and all – in Rodger’s voice. Anders Haugen and his brother Lars become the main characters to illuminate the heyday of American ski jumping, the dominant discipline in skiing before WWII, with Rodgers recounting the brothers’ countless national titles after the formation of the National Ski Association (the former name of U.S. Ski & Snowboard).

After detailing Anders Haugen’s foray into winning US Skiing’s first Olympic Medal at the 1924 Chamonix Games, Rodgers shifts to Lars trouncing over the Colorado Rockies between Estes Park and Steamboat Springs with skiing pioneer Erling Strom. From there we follow Strom ascending Denali on skis for the first time with Al Lindley, a Minneapolis-debonair who represented the US at the 1932 and 1936 games. The whole time we’re treated to a storytelling style which forgoes lyricism in favor of carefully plucked anecdotes that set them in a Midwestern simplicity and witticism which reaffirm the place these stories emanate from.

The best, most fully expressive character in the book hops off from Lindley, with his wife Grace Carter. Carter and Lindley met at the tryouts for the 1936 Olympics, with Grace becoming one of the first two American women to represent the US in skiing on the Olympic stage. Her story begins the earnest exploration of the exclusion and challenges that women have faced surrounding skiing since the sport’s inception in the United States. We follow her courage, effervescence, and brilliance through to the end of her life in 2002 in Duluth.

Carter shines through best when Rodgers puts her attitude towards the skiing world that tried to exclude her in her own words, citing a column she wrote in the 1960s where “several times each year parents asked her if they should allow their daughters to race. ‘I usually tell the parent no…because that’s what he wants to hear…if a girl is really keen she’ll race anyway. When the girl asks me, I say yes.’” Carter’s attitude also seems to sum up the broad arc of women’s sporting history, which is one of the key themes of Winter’s Children.

Skiing, at points, has been a site for progressive attitudes towards women’s participation in sport, but at others, it’s also been caught up in the same history of misogyny found elsewhere.

Earlier than one might expect in his history, Rodger’s starts to introduce characters that some of us may have shook hands or looked up to out on the trail during our own lifetimes. At that inflection point lies one of the most poignant reasons to read Rodger’s work; the inclusion of snippets from an interview with George Hovland, capturing the former Olympian and Midwest’s foremost ambassador of the sport earnestly reflecting on his life’s work shortly before he passed away, at age 94, last May.

In the context of Winter’s Children, the reader can fully pair the vignettes Hovland might offer you if you were lucky enough to run into him out at Chester Bowl in Duluth with the full life and joy that he first found there as a youth in the 1940s. Back then, the Bowl was home to a ski jumping scene that was something akin to what one might find at a skate park today.

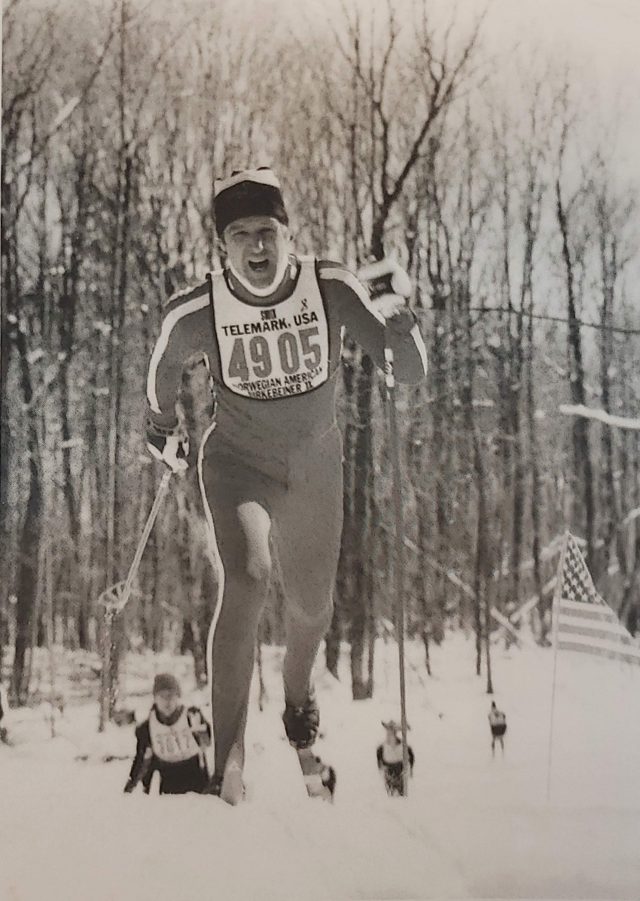

The strength of Winter’s Children is not only remaining in, but building on, the mythos of those types of characters and those types of places strewn across the Midwest. Rodgers makes it foundational, with the most widely-known myths in the sport – that of the Vasaloppet and Birkiebeiner – being recounted in the first pages. When Winter’s Children does get to the Midwestern revival of those myths with the founding of both the Mora Vasaloppet and American Birkiebeiner in 1973, there is an ironic coming back down-to-Earth. It’s when the history starts to feel more vivid. When, for many readers, the recollections on the page will mix with those in their own minds. Of their own experience, perhaps.

That leads to the temptation to say that things aren’t how you remember them in Rogers’ words. You might think ceded some of its accuracy and cohesiveness as it gets closer to the present. If the reader catches that thought, they should hold two idea’s in mind. 1) First and foremost, is that Rogers’ is most likely correct, this is a painstakingly well-researched project, and 2) that their own mind’s wanderings add to the folk history that Rogers’ set out with here. Rodgers’ biographical sketches of Bill Koch (who isn’t a Midwesterner, but did design the trails at Telemark, and that seems like tangential connection enough to explore his influence here) and Jessie Diggins aren’t nearly as fleshed-out and richly-woven into the story of skiing as the athletes who came a half-century before them. He stops the story of the Birkie right after its originator Tony Wise loses control of the race in 1985, without detailing how the race continues to be the “Rome” in Midwestern skiing’s empire – all the youth skiing, citizen racing, and training developments seemingly leading to it. That’s ok, those histories and those stories continue to go on. Reading their introductions here is a great primer to join in.

There are the accurate appraisals, too, on modern issues in the community – climate change, the influx of money into youth training programs, and the lack of racial and socioeconomic diversity in the sport. They all remind the reader that the individual and communal elements of nordic skiing’s history are both active agents. Rodger’s can’t fully portray the sport as it is today, sending us as readers back to the ether and implying that you yourself need to feel them as part of the living, breathing, gliding AND kicking community of nordic skiing as it continues its odyssey here and now.

That theme: the vitality of skiing’s history, is how Winter’s Children comes to an end. Our rhapsode, Ryan Rodgers, ends by tying up the loose ends of the narrative thread of Charlie Banks and Mark Helmer.

It is a long one. We are first introduced to Charlie Banks when he wins one the first Minnesota High School State Meets in 1941, before he fights in WWII, returns, and splits for the forests that extend past the Duluth hillside. Living an ascetic, but sturdy life in those Northwoods, Banks cut a trail system called Korkki on his property where he started the oldest continuous race in the Midwest, the Judeen Memorial 10 k, in 1962. Twenty years later, Mark Helmer was living down the road and decided to ask Banks if he could use the trails.

The meeting soon evolved into a deep friendship built around skiing, saunas, and more than a few PBRs. Banks sold Helmer 20 acres of his property in 1993 to build himself a house and a warming chalet at the trailhead of the newly public Korkki trails. Banks passed away in 1998, with Helmer saying in an interview for Winter’s Children that “he was my best friend and still is my best friend; there isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about the man.” It is one final parable that points towards the magical juxtaposition at the heart of nordic skiing – a cold, individual pursuit that brings out the warmest of human connections.

A simple sport that was, and still is, the core around which a person can organize a life.

Winter’s Children: A Celebration of Nordic Skiing by Ryan Rodgers is available at local bookstores and ski shops throughout the Midwest, major book retailers, and online from the University of Minnesota Press.

Ben Theyerl

Ben Theyerl was born into a family now three-generations into nordic ski racing in the US. He grew up skiing for Chippewa Valley Nordic in his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, before spending four years racing for Colby College in Maine. He currently mixes writing and skiing while based out of Crested Butte, CO, where he coaches the best group of high schoolers one could hope to find.