The “First Tracks” series highlights the pregnancy, postpartum, and parenting experiences of noteworthy athletes in cross-country skiing in various stages of their professional careers. The sharing of these experiences can benefit athletes in any stage of their career, whether they are an elite or recreational skier, by demonstrating that it is very possible to return to skiing, competition, and an active lifestyle with a growing family. The series will include the physical challenges of being an athlete during and after pregnancy, balancing family life with skiing, and the joy that starting a family can bring. This is part two of Brooks’ “First Tracks”. Click here to read part one of this conversation.

While Brooks was able to exhale a small sigh of relief when she passed the 13-week mark with her twins, she was acutely aware that she was not out of the woods in terms of other complications. At about 15-weeks, Brooks was diagnosed with a condition called placenta previa, which means that one of the twin’s placenta was lying over the opening of her cervix. This condition increases the likelihood of bleeding and preterm labor and increases the risk of complications with the placenta, which is a baby’s lifeline in utero.

Typically, when a woman is diagnosed with placenta previa, she is instructed to be very cautious with exercise and not to engage in high-impact activities that would create stress on the placenta, like running or jumping. Brooks continued to stay active by walking and hiking and was much more wary about anything that created a potential for a fall, describing herself as having a “preservation mindset.” She did do some skiing on trails in the winter and some crust skiing in the spring, both of which she felt comfortable with as she has spent so much of her life on skis and could be cautious not to fall.

“I stopped running pretty much right away,” she explained. “Then everything else was just being really careful about what risks I decided to engage in.”

Her experience during pregnancy was much different than many athletes who share their stories on social media, but she takes pride in her experience and wants to promote the message that being unable to stay at the top of her game through the journey was not something she should feel badly about.

“I just want to show a diversity of experiences amongst athletes,” she explained. “If I had gone through this when I was still trying to compete, it would have been really hard slash impossible. But there are lots of other examples where it is totally possible. You know, Kikkan [Randall] and Caitlin [Gregg] are doing pull-ups with weight belts at eight-months pregnant. And that’s fabulous, but I think it’s really important to show the other side and to make sure people know that if that’s not their experience, that’s absolutely okay and there is nothing wrong with them or that experience.”

That is not to say that the adjustment from Olympic athlete to a pregnancy where her activity was tempered was easy.

“It was definitely really hard,” she expressed. “But I felt like I wanted it badly enough that I had to be okay with it. I didn’t really have an option.”

Brooks was forced to reduce her activity level and let go of her performance ready body long before she was sidelined by the placenta previa. During her initial quest to regain her cycle through HRT, she was instructed to stop working out and to eat more in order to gain weight. She described the mental shift that accompanies watching her body change and her fitness dissolve.

“It’s like telling your body, ‘Hey, you don’t have to be this super fit person anymore. You can calm down. You can afford to use your energy for things like getting pregnant instead of recovering from this workout.’”

She added that this is certainly not everyone’s experience, as many women are able to conceive at their peak level of fitness and remain very active throughout pregnancy. But it was her experience and it is an experience many women face surrounding pregnancy.

Though the placenta previa resolved after a few months, the couple had a few other scares during early pregnancy as their doctors had some concerns about Ruby’s kidneys. Luckily, this did not result in any problems and she otherwise had a smooth pregnancy.

Because she was deemed high risk due to her age, the fact that she was having multiples, and her experience with loss, her doctors selected a date that would be shortly after she reached the 37 week mark if she did not go into labor sooner on her own, as twins are commonly born before they reach full term. Brooks remembered feeling nervous as her pregnancy progressed that she would have preterm and have to be put on bed rest, or that her blood pressure would rise and she would develop preeclampsia, but she remained healthy all the way to her induction date.

“I remember the day before, my husband told me, ‘I think we should wait. I don’t think you should be induced. I really think you should go into labor naturally.’ And I looked at him and was like, ‘You know what, it’s really not your choice,’” she laughed. “I was just ready to be done.”

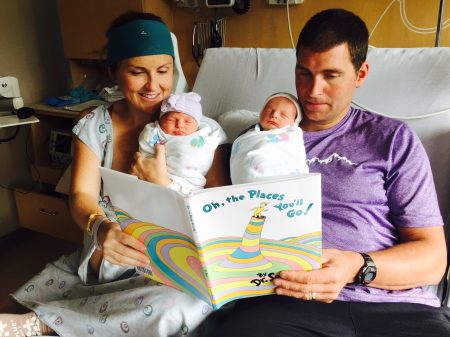

Brooks and Whitney headed to the hospital on the induction date where doctors began to administer Pitocin to begin the labor process. Both babies were head down, which was a positive indicator that she could have two smooth deliveries. She recalled that it took a while for the drug to take effect. The couple waited anxiously in a labor and delivery room, before being transported to an operating room (OR) when she had dilated significantly and her body indicated she would be ready to begin pushing. She explained that multiples are typically delivered in an operating room because of the high-risk nature.

“My daughter was born and I think there were seventeen people in the room,” she said. “There are just teams of people. There is a NICU team, each baby has a doctor, and each baby has a set of nurses, and the anesthesiologist. It’s kind of like the movies.”

She also added that the time between deliveries for twins is typically very short, often within five minutes. That was not the case for her daughter and son.

“My daughter was born and then my son didn’t want to come out.”

She continued to push, but her son was not making progress.

“After quite a while of trying to get him out, we actually left the OR with one baby born and one baby still in utero,” she said. “And I remember a nurse telling me, ‘I’ve never left the OR with only one twin.’ So that was a little scary.”

After pushing for three hours, her doctors restarted Pitocin to intensify her contractions, helping push her son out. But the baby was not responding well to this stress and his heart rate dropped dangerously low with each of her contractions. Eventually, Brooks was wheeled back into the OR for a c-section, where her son was delivered successfully.

“So not only did I get twins, but I have a boy and a girl, but I also had both a vaginal [delivery] and a cesarean,” Brooks added. “So the joke is that I wanted to experience it all.”

Regardless of what type of birth a woman experiences, she undergoes a significant amount of physical trauma. Because she experienced what she referred to as “the double whammy”, Brooks faced perhaps a unique set of challenges as she allowed her body to heal.

“I always tell people, ‘Well, I feel like I’ve done a lot of hard things in my life,’” she said. “But we spent about a week in the hospital afterward. And it’s really hard because you have both traumas, and when you have a c-section, you’re not supposed to lift anything for quite a while, but then you’re also responsible for feeding two babies. It was definitely tough and it took a long time for me to get back to exercise.”

For Brooks, the process of recovering from her birth experience was not something she wanted to rush through. She respected the immense toll the experience of infertility treatment, a twin pregnancy, and both types of delivery placed on her body.

“I remember, I think it was the first week of being home, and I tried to go for a walk and I made it about half a block and I went home,” she recalled. “I was like, ‘I know this is not right. I can’t do this.’ I had the perspective that I wanted to be patient. I didn’t want to rush into anything. I think we’ve created this culture where it’s kind of a competition to see who can get back and run a 5k within the first month of giving birth. And I don’t think that’s a fair expectation to put on women postpartum.”

Brooks avoided this society and social media-induced pressure and gave herself the grace to ease back into activity slowly in ways that felt best for her own recovering body.

“The doctors will tell most everyone that they’re cleared to run at six weeks, but you still have so many pregnancy hormones going through your body,” she expressed frankly. “Your entire body is loose and just the probability of getting super injured is really high. So walking and pushing a stroller was essentially what I did for months.”

Transitioning to life with one newborn is an adjustment to say the least, much less multiples. Brooks laughed that her parents had her triplet siblings when she was just a toddler, so the chaos was not as foreign to her. Her mother, the seasoned pro, flew out to help Brooks for the first month and her husband took what time he could for paternity leave. She felt fortunate that she had help, but she expressed that the adjustment while recovering from her birth experience was still very difficult.

Regardless of how a mother chooses or is able to feed her child, the process is time consuming. At birth, a baby’s stomach is only about the size of a marble, meaning babies need to be fed frequently.

“Feeding two babies every two or three hours is definitely a full-time job,” stated Brooks.

She described the process of trying to breastfeed twins as “an acrobatic challenged”, as she was always juggling to get them into position, keeping them both content if one fed longer than the other, or trying to burp one while the other kept feeding.

“Essentially with twins, the best way to do it is to feed them at the same time and you do the double football hold,” she explained. She then described sitting on the couch surrounded by pillows tucking each baby under her arm Heisman-style until they were both finished eating.

“Once you have them there, you are just – you’re not moving,” she laughed. She then recalled the deathly thirst she would be struck by as her milk let down.

Brooks described nursing her twins as an “adventure”, but also something that was manageable for her. She was able to exclusively breastfeed her twins the first four and a half months, before beginning to supplement with organic baby formula. She eventually tapered off pumping around ten months.

To illustrate the reality of this adventure, Brooks shared a story about her experience supporting US Nationals in 2018, which took place in Anchorage as the final major domestic competition prior to the Olympics in PyeongChang.

“Even though Rob and I both have jobs and had two 4-month-old infants, we were signed up to be joint chiefs of awards,” she said. “This was a much bigger job than initially intended! We spent New Years raiding the Christmas Tree dumps (once with the kids in their car seats I think?) so we could host wreath and bouquet making parties for flower ceremonies each race day. Then on race day Rob and I had a system where he would drive, the kids would be in back and I would literally pump in the car all the way out to Kincaid such that when my feet hit the ground I could have as much time as possible to volunteer before having to feed or pump again. I definitely got caught (semi-naked) a couple of times, but I didn’t care! We had our kids out there the entire time.”

On July 1st, Brooks announced that she had officially become a licensed professional counselor in the state of Alaska. The title was nine years in the making, requiring a masters degree in counseling psychology, 3,000 post-graduate clinical hours, and a comprehensive national board exam. She chipped away at these requirements while still training for and competing in two Olympics, followed by the detailed journey to and through pregnancy detailed here.

Since ending her ski career, Brooks has run her own business, Holly Brooks LLC, where she offers counseling, coaching, and consulting. She explained that these words are used inclusively and that as her business has involved, the word “coaching” has become open-ended, as she now does little physical coaching, primarily focusing on performance and mindset coaching.

“I would say, my business has pretty much transitioned into mindset coaching and mental health counseling,” said Brooks.

Because she had built her own business and was running the show on her own, it was difficult for her to take a significant step back from working after her twins were born.

“As far as return to work, when you are your own boss, you can pretty much do whatever you want,” she explained. “But when your business is only you, I have a client load that, of course, I had people to refer to, but it’s not really easy to say, ‘Hey, I’ve been seeing you for a year and a half, I think you should go see this other person now.'”

As she felt her clients were depending on her, she returned to work quickly.

“All of my clients were very aware of my situation, and I ended up working until about a week or two before the babies were born, and then I was able to see some clients electronically, and I think I saw my first client when the babies were two weeks old,” she recalled. “Which is crazy, because I don’t even know what I was thinking or if I could see straight.”

She explained that apart from being relied upon, the challenges of being self-employed include the fact that she would not have any paid time off during a time when their family expenses increased exponentially with the new additions.

Her return to work was rapid, but her return to sport and physical recovery in a broader sense than just recovering from the birth itself were much slower. Some of the complications she experienced as a result of carrying and delivering twins have resolved, while others are still present.

“Some people say they come back stronger after kids,” she said lightheartedly. “And some people tried to tell me that and I was like, ‘Do you realize that I was a professional athlete before? I don’t think I’m going to come back stronger.’”

She added that she was only speaking to her own experience, not making the generalization that it would be impossible to do so, pointing to her former teammates Kikkan Randall and Caitlin Gregg, both of whom she affirmed “were doing awesome.”

Issues with core strength and pelvic floor functionality are not uncommon in the population of postpartum women. As Brooks’ body grew to accommodate two nearly full-term babies, the muscles in her abdominal wall stretched significantly, leading to a condition called diastasis recti, which is a separation of the rectus abdominis muscles making up the outer part of the abdominal wall. (Randall discusses this complication here.) Brooks completed physical therapy to help reclose these muscles, but because of the extent of the separation, the condition has not and may never fully resolve.

She also explained that she experienced some prolapse, though she did not see the need to go into too much detail.

“I’ll let people look that up on their own,” she laughed. “But it’s very common.”

As a result of the prolapse, she has experienced some lingering problems with bladder incontinence. She recalled working with a group of female masters prior to giving birth and being confused at why these women refused to do box jumps. She now fully understands their reasoning.

While working with a postpartum physical therapist or pelvic floor specialist can greatly reduce or eliminate these complications, Brooks explained that in balancing all of the aspects of her life, this type of care got cut out from her time budget.

“I did do some postpartum PT, pelvic floor PT [early on], and I think that helped,” Brooks explained. “I should probably go back, but it’s all a matter of time. I have very little time, so just figuring out how to spend that time is huge.”

Brooks expressed that time management has been a major factor in her return to sport. About a year and a half prior to having her children, Brooks and her husband moved into their current house, which is directly across the street from a trail system where they can ski in the winter and run or mountain bike in the summer. This has been a key factor in Brooks’ return to an active lifestyle, particularly early on when she was trying to sneak out for exercise between her babies’ feedings.

“People that have kids know this, but you lose so much time in transition,” she said. “Loading up the car, getting into the car, getting out of the car, loading the stroller, and doing all of this. I feel so lucky that we live across the street from a million-acre park, so we have the skiing and the running and the mountain biking literally outside of our door. So I feel so lucky to have that because it makes it so much more accessible.”

While relocating may not be possible for everyone, she recommends that people that want to stay active after starting their family to think about ways to remove or reduce barriers to being able to exercise, whether that be purchasing a treadmill or home gym equipment, or choosing an activity close to home.

“Especially early on, when you’re breastfeeding, you have very little time between feedings,” said Brooks. “So if you get out and do something and can cut out the commute time, it’s awesome.”

Brooks stayed modest in her evaluation of her current level of fitness and postpartum recovery, expressing that in theory, she has improved in both regards over the last year.

“I have more time because the kids aren’t breastfeeding,” she explained. “But I have less time because they’re mobile and they’re drawing on my laptop with sharpie pens. In theory, I’m further away from that postpartum mark, so I think a lot of things are better, and I’m also just mentally used to the craziness of being a parent.”

In early June, Brooks participated in the Alaska Run for Women, a five-mile road race in Anchorage that raises money for breast cancer research and women’s health. She stated that going into the race, she was unsure whether she would run faster than she had the year prior when she finished the race in 31:56. Despite her feelings, she bested her time by nine seconds, finishing in 30:47, a pace of 6:22 per mile and a far cry from being out of shape. (Rosie Brennan took second in the race in a time of 27:48, followed by Kikkan Randall who finished in 29:29 about one month prior to finishing her breast cancer treatment.)

“It’s almost like I feel in my mind that I’m not in as good of shape, I think just because I am further and further out from my professional career,” Brooks reflected. “But I think compared to a year ago, I am stronger, even if it doesn’t feel that way all the time.”

Finally, Brooks offered a message to sum up what she wanted to convey to other women by telling her story.

“I just really want to tell people that whatever journey you’re on, it’s your journey and it’s your own,” she emphasized. “It’s really, really super easy to get caught up in comparison, whether it’s you can get pregnant or you can’t get pregnant, or ‘My body doesn’t look like that person’s body at eight-months pregnant,’ or ‘How did this person run a marathon at four months postpartum and I’m still having a hard time getting out the door?’

“I think it’s really important for people to be aware of themselves when they’re doing that to just try to use some self-compassion and kindness toward themselves and toward others,” she continued. “We’re all on our own independent journey and there are lots of different ways to have a family, and to have a family and be an athlete, and it’s going to look different for every single person. So I would just caution people to think through and think with that lens.”

Simply put, “It’s different for everyone and don’t beat yourself up if it’s different for you.”

In the coming months, Brooks will be pursuing certification as a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder mental health specialist, a topic she is particularly passionate about in light of the experiences of her own experience and the experience of women and men in her community. She explained that these conditions are very common across both genders, as both men and women can experience postpartum anxiety, depression, or psychosis.

“People plan for ski races, or birthday parties, or buying a house,” she explained. “But I feel like there is this extreme lack of planning for how having a kid is going to affect your life, and I think it’s the biggest transition that anyone will ever have in their lives. So I would really encourage people to set aside some time or to seek out some professional health in that arena. And for people to be aware that perinatal mood and anxiety disorders affect one in seven or up to one in five women and one in ten men.”

She plans to offer expectant parent coaching through her practice to raise awareness about these issues and to counsel families through the preparation process.

“It is a big change,” she stated. “And I don’t say that wanting to be a Debbie Downer, or wanting to scare anyone, but I think that knowledge is power. If you plan for a ski race or something like that, then maybe you should also plan for the biggest change, potentially, in your life. It’s all perspective. For me, having kids was a bigger life event than going to the Olympics.”

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646