This story could be about many things; developing coping mechanisms when a stay at home order is in effect; finding ingenious ways to elevate the heart rate in a small space; fighting the urge to deem outsiders as outsiders; knowing when to check the urge to be selfish.

Obvious disclaimer here, I live in a tourist town, Bend, Oregon where it’s clear tourists and fresh-air-seeking coronavirus “refugees” should abide by the city’s discouragement of non-essential travel to Bend. Further, local sno-parks are closed as are the major trailheads for trail running and mountain biking. Grooming for xc stopped a few weeks back. Enforcement aside, and personal discretion aside, many locals are running and riding from the house. Some still ski.

Then there’s the scanning of license plates that many mountain town dwellers have become accustomed to. It’s clearly not the usual summer or winter tourism bump. It’s something different and unsettling altogether.

Across the street from where I’m writing, a quaint cottage was recently rented by folks from Nevada. Grabbing groceries the other evening, my rough math calculated about 15 percent of the vehicles in the parking lot were from out of state. There was the tricked out Sprinter with Washington plates and an REI superstore’s worth of kayaks and mountain-road-gravel bikes secured to the exterior. The fit middle aged couple perched in the front pilot seats were glued to screens, looking like they were poaching WiFi from the adjacent Starbucks. My brain went there: Adventure refugees from a Covid-19 hot spot. Truth is, my people fled Europe. The regional xenophobia welling up felt dirty.

That brings us to one of the loveliest mountain towns in North America, Sun Valley, Idaho. There’s Hemingway’s legacy, the Big Wood River and its trout, a Mt. Baldy hill climb, thin-air mountain biking, locals only backcountry stashes, and timeless cross-country skiing. And according to a recent NPR piece, no one should go to Sun Valley.

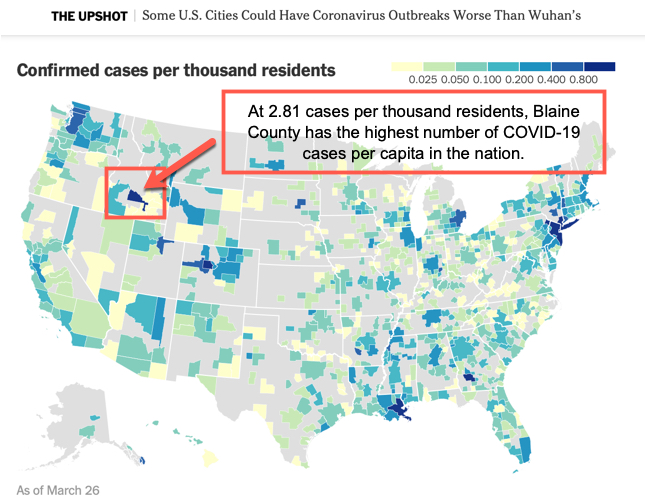

Blaine County, where Sun Valley is located, has experienced one of the highest per capita rates of Covid-19 in the U.S. (This remains a reality among some of the West’s ski towns.) It appears the virus was spread when non-locals visited large social gatherings at the end of February and early March. Adding to these anecdotal possible vectors was the major ski resort in town, which shuttered effective March 16. Until then, it was business as usual. Tourist and second home owners flocked to the area where the fine skiing was primed with bluebird skies.

“Schools around the region were closing, not here in Blaine county, schools in Seattle, schools in San Francisco, schools in St. Louis, Chicago, Southern Cal, all starting to close, and people starting to work from home,” observed Betsy Youngman, a longtime Sun Valley force in the cross-country community. “So people that could afford it got in their cars, their private jets took flights into Blaine County, into Sun Valley.”

Sun Valley became an obvious escape valve. We also all know now, this was a perfect storm for coronavirus transmission. With one post-office and a single grocery store, packed slopes, and trails, the possibility for community spread was rife.

A town like Sun Valley is not alone in the mountain kingdom when it comes to reconciling income inequality. Most often, residents lower on the tax bracket do more than make do – mountain vistas and easy mountain access are a wonderful pacifier. But with the influx of coronavirus and a thriving travel industry, these are unique, and tension riddled times.

“A city or a place like Sun Valley, or a region like Blaine County would not exist without the wealth that comes and goes and the people that are incredibly generous,” said Youngman. “That is why we have a free summer symphony. That is why we have ski trails and the bike trails we do. Generally it is a very welcoming and grateful community that people come here and spend their money so that those of us that live here year round can live in such a beautiful spot with beautiful amenities. This is different because what was happening, that has now been shut down, some refugees that are coming from the bigger cities have come in sick.

“And so, yeah I think there’s more tension than normal, we’re looking at the license plates, who is parking at the grocery store, the trailhead, or in my neighborhood because they very well could be sick. We are willing to be compassionate. We had a neighbor come in from Chicago who was here three days and came down with the Covid-19. The other neighbors said how can we help? Can we get you some groceries? So we went to the grocery store, we dropped some things off on his front porch.”

Youngman also explained the community has bonded as it looks after its elders. She noted that Sun Valley’s average age is approximately 60, making its population particularly susceptible to the worse effects of the virus. Youngman and others find themselves checking in on residents like Charley French (93) and Shauna Thoreson (85) — both frequent World Masters racers and age group winners.

What is real in New York City is also real in Sun Valley. A run on groceries. Scarce medical supplies and personal protective equipment at the local hospital were suitable for mishaps, even the rare emergency, not a pandemic. Many small mountain towns have high per capita rates of Covid-19 cases and lower per capita rates of vital resources like ventilators.

Sun Valley is on lockdown. Non-essential travel or business conducted outside the county is forbidden. For those entering Blaine County from out of state, even if you are a local resident, you are looking at a 14 day quarantine.

It’s worth mentioning, and we hope it remains clear: DO NOT TRAVEL TO SUN VALLEY. Some readers live in places where outdoor activities are currently restricted. Bend is but one example. To be fair, local communities are navigating a climate where defining “essential activity” has become blurred. (Ask me a week ago if spring ski mountaineering was “essential”, I would have given you an unequivocal, “yup”. I was wrong.)

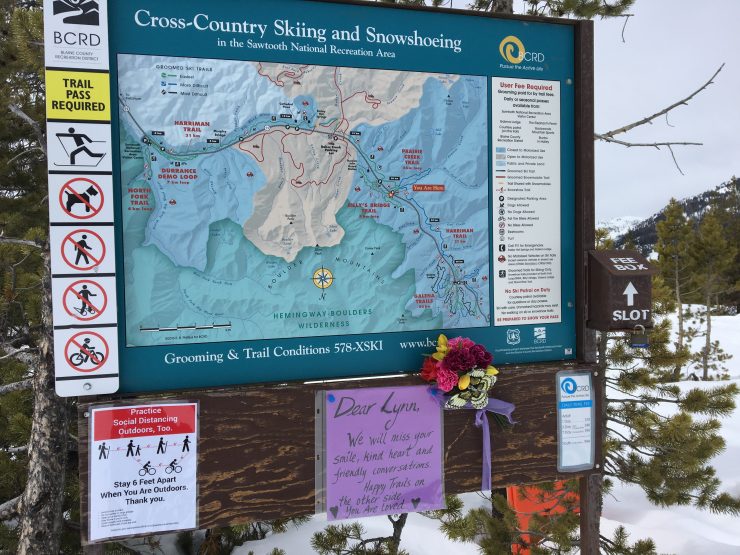

For Sun Valley residents the way the state has weighed best social distancing practices and defined “essential” means cross-country skiing remains a wellness outlet. The BCRD, or Blaine County Recreation Department, continues to groom cross-country ski trails — for locals.

“I think at this time of year it is an essential service, for recreation and social distancing,” said Youngman. “You can cross-country ski safely on our 200 kilometers of trails, and stay six feet apart. When summer comes, when we are sharing trails that are two feet wide and are hiking, it is going to be harder to keep that six foot distance from one another As long as we behave, I think it is great we are grooming, It is giving people an outlet. It is giving people a healthy place to go and help their immune system by getting some exercise. We don’t have other places to go until the snow is gone. I think everyone is relieved.”

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.