This profile is part of a ‘Where Are They Now’ series, made possible through the generous support of Fischer Sports. Learn more about their products at www.fischersports.com.

Despite getting his start as an athlete in Brattleboro, Vermont, moving back to the Green Mountain State wasn’t specifically on Jim Galanes’ list of things to do in the coming years.

Yet that’s exactly what the three-time Olympian has found himself doing, after expressing an interest in a job with Graham and Mila Lonetto at Edgewise Ski Service in Stowe. Turns out, it was a perfect fit.

“I had been talking to the folks here at Edgewise for a couple of months,” Galanes said in a phone call last week. “I came back and interviewed with them and talked some more, and I just felt really comfortable with Graham and Mila, and I really like their business model and their philosophy. I thought it was a great opportunity for me.”

In taking over as manager of the stonegrinding operations for both nordic and alpine skiing, Galanes is at the same time returning to the ski industry seven years after leaving his position as head of the Alaska Pacific University (APU) program and taking on something new. Among his tasks is to develop the smaller nordic side of the business operation, which means settling back into the community and connections that he enjoyed for so many years. And through his experience as an athlete and a coach, he has tested a lot of grinds, and even did some of his own on machines around the country.

But helping to develop a grind system? That’s new.

“Back when grinding first really started to come into the sport, I worked a lot with Nat Brown on testing his grinds that he was doing,” Galanes says. “He was really the first guy in the country set up to do strictly cross country grinds. I’ve had a lot of experience preparing skis and testing grinds, and it will be fun to develop our own system of grinds here.”

There’s no reason to think the results won’t be excellent: besides the Lonettos’ expertise in stonegrinding for alpine skis, there’s the persistent drive for excellence that Galanes has shown throughout every aspect of his career. For instance, he started his athletic career by winning three national titles in nordic combined and two World Cups. Most people would consider that pretty satisfying.

Not Galanes. Instead of resting on his laurels, he switched sports.

“That was real easy,” he laughs, recalling his decision back in 1979, when he was 23 years old, to focus only on cross country skiing. “Jumping was really hard, and hard for me to perform consistently… I was successful at times, but it wasn’t the consistency of success that I was looking for. My cross country skiing was continuing to improve, and that made it an obvious decision to me.”

Back then, nordic combined was “old school.” Galanes trained mostly as a cross country skier, and the national team didn’t always have a coach, much less a specific jumping coach. So the switch was easy, and he joined a men’s team that was the best the U.S. has ever seen. Bill Koch had won his silver medal in the previous Olympics; Tim Caldwell, Dan Simoneau, and Audun Endestad were at or coming into the peak of their careers.

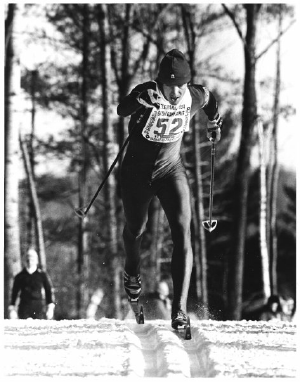

In that competitive atmosphere Galanes thrived, winning ten national titles, competing in two more Olympics (he already had one under his belt as a combined skier), and collecting a top finish of fourth place in the final World Cup race in Russia in 1984. Historically, he’s among the best skiers the U.S. has ever seen.

His individual finishes were his first big contribution to American skiing: the results by American men from that era still inspire racers today. Current star Kikkan Randall, who has now won two international Sprint Cup titles, calls Galanes’ era of racing “the last Golden Era.” It’s a reminder of what is possible, even as Americans and Canadians still seem to reach new heights every year.

But Galanes didn’t just want that success for himself and his teammates; he wanted it to continue. And so his second contribution, and most would agree an equally huge one, is through coaching and vision. After heading the U.S. Ski Team women’s squad and the Stratton Mountain School for a few years each, Galanes went on to found APU, introducing the club system that currently sustains elite skiing in an era of meager budgets from the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association.

Up To Alaska…

In 1995, Galanes was in Anchorage, Alaska, where he started APU and called it Gold 2002.

“I really believed, at least when we started that, maybe a gold in 2002 was a little bit of a reach, but I really believed we could step up to the level of being competitive,” Galanes says.

Today, APU is a behemoth of American skiing. Then, there was nothing like it: skiers at every age and level, multiple training groups, racers who attended U.S. Ski Team camps, athletes who were taking college classes but were not competing on the NCAA circuit – all under one club umbrella.

“It came from a fundamental belief, and I still believe this, that the U.S. Ski Team can’t be everything to everyone,” Galanes says. “You can’t have a coaching program and a high-level training program just at the time when you’re at camps with the U.S. Ski Team, and then be on your own. My vision was to have a high-level program that was community-based, that the community supported and was behind and felt part of. I thought that was really critical to long-term success and more importantly, sustainability of the program.”

Hence, the many levels of skiing. In the beginning Galanes was coaching two or three, sometimes even four, training sessions per day.

At that point, Randall was a sophomore in high school, focusing on running. When her coach left town, she needed a new training group, and a family friend mentioned that two guys – Galanes and Frode Lillefjell – were starting a junior program at APU.

“Within a few weeks I was hooked, and I changed my focus from running to skiing,” Randall wrote in an e-mail this weekend. “So it was rather serendipitous that this new junior ski program was starting up at the time when I was looking for a training group! … I always found Jim’s technique advice to be helpful and easy to understand. He was actually quite a good motivator out on course as well.”

She has raced in the APU suit in domestic races ever since, and says that Galanes “certainly has been a very influential part of my career.”

Furthermore, developing from a junior to a senior, a World Cup skier to then a World Cup winner, was easy for her at APU.

“I was able to take classes during the training season and then have opportunities to race internationally at the developmentally appropriate stages (World Juniors, U23’s, OPA Cup),” she wrote. “I always had the club team support and daily training sessions when I was at home, race support domestically and then the U.S. Ski Team camp and competition opportunities on top of that.”

She thought about taking a year to do NCAA racing, but decided against it.

“Jim’s opinion was that many of our talented U.S. skiers lost too much ground to their counterparts in the rest of the world while racing in the NCAA system,” she wrote. “He felt it was imperative to train at a high level right out of high school and fit in school around the training… Jim and Frode believed it was possible to reach international success, it was just going to take a different approach then most of our US skiers had been taking. I agreed with them and together that is what we set out to do.”

But while Randall remembers her development being smooth – the hardest thing, she wrote, was to have patience and remember that it as many small steps that would take her to the top – Galanes had a few things to add on that subject. Eschewing the NCAA option for older juniors and skiers in their mid-20’s was not always a popular strategy, and APU also did not always receive full support from the U.S. Ski Team, despite earning Olympic nominations for several athletes.

“It was challenging at times – about the same time I founded the APU program, the U.S. Ski Team was to loosely support club programs,” Galanes says. “But then a couple years into that they went to a highly centralized focus, trying to strongly encourage people to relocate to Park City, which for a variety of reasons didn’t make a lot of sense to me. I felt it was detrimental.”

Luckily things loosened up again, and the national team now relies on clubs like APU and praises them for their work in athlete development. Galanes’ idea was that when athletes went home from their U.S. Ski Team training camps, they should have reliable, high-level coaching and training partners. The national team more or less requires that of its athletes at this point.

“In the last five, six, seven years, their collaboration with the regional programs and clubs is what has led to the success,” Galanes opines. “It has been key. Those are the coaches who are working with those athletes and developing those athletes, and they know best… I think that the sustainability and the success that we have now is focused on those programs and more of them around the country. I hope we can keep it going.”

Galanes does not believe that the American ski community has reached the saturation point for these sorts of clubs. But to fill all the “pockets of interest” isn’t easy, as a few startup elite squads have discovered in the last few years.

“I don’t think you can hatch a plan or craft a program proposal and go out and shop it around, and try to get the funding up front,” he asserts. “Funding follows success of the program and support from the community where the program is based. So you’ve got to bootstrap those programs for a little while to get to the point where you can enjoy the funding…. it was extremely tough.”

… And Back to Vermont

After 2006, Galanes stepped away from the APU club that he had founded. It has, of course, continued to thrive: four of eleven current U.S. Ski Team members are APU athletes, and this spring head coach Erik Flora became the first nordic coach to win the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association’s Coach of they Year Award.

Galanes is happy to see that success. For himself, though, instead of seeking another coaching job, he pursued life outside of skiing.

“I spent basically 32 years doing nothing but focused on high-level skiing,” Galanes says. “I felt it was time to do something different, learn a different area professionally, and move on.”

He worked for an engineering firm in Anchorage, and then moved to Sun Valley, Idaho, for a stint. Of course, he wasn’t completely gone from the ski world; he continued to do a bit of consulting, personal coaching, and advertised a masters training group in Sun Valley. “I keep up to date,” he says.

But the job at Edgewise is by far the most decisive step back towards the sport that Galanes has taken since leaving APU. And he seems excited to join Graham Lonetto, a former serviceman for the U.S. alpine team.

“They have an amazing setup here and some great equipment that not many shops in the country have,” Galanes says. “We’re a race shop, we’re focused on high-level performance skis. Whether that is for a masters skier or a U.S. Ski Teamer, we’re going to be targeting that whole market.”

But he also has some more specific ideas of how Edgewise can best help the nordic community.

“The goal is going to be to keep it simple and focus on coming up with some good, broad-range grinds,” Galanes explains. “When people get so specialized, you have to have many pairs of skis to match to the snow conditions. Not a lot of the customer base that we’ll be working with, college skiers or ski academies or masters, have that big a fleet of skis… A kid with two pairs of skis can’t have a narrow-range grind.”

In either the super-specific or broad-range realm, he’ll have competition. Stowe is just two hours from Putney, Vermont, and Caldwell Sport. If a stonegrinder can be famous in this country, then Zach Caldwell certainly is, and Galanes is setting up shop in his backyard.

So what, says Galanes.

“First of all, Zach is a good friend of mine, and he has been a key advisor for me as I’ve moved into this role,” he explains. “I’ve talked to him quite a bit, and he has a wonderful attitude about it. You know, competition is good, and it’s going to force everyone to do a better job and the winners are going to be the skiers.”

There’s good reason to think that local skiers might win for other reasons, too. If Randall’s testimonials say anything at all about Galanes, it’s that any ski community is lucky to have him.

“Jim is incredibly passionate about cross country ski racing and has such a deep bank of experience from being an elite racer himself during the last golden era of U.S. cross country skiing, plus having coached so many top U.S. skiers,” she wrote. “He is very good at thinking and analyzing and conceptualizing.”

So is a return to coaching a possibility? Not right now, Galanes says. He’s too busy settling into a new town and a new job. But in the future, he certainly hopes so.

“I think I’m good at coming in and offering perspectives on technique, and how to implement technical changes, and how I see things,” he says. “I’d like to do some of that, go in and talk to coaches and athletes about how I see technique. I think that could benefit programs and people quite a bit.”

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.