(Originally published in the Anchorage Daily News)

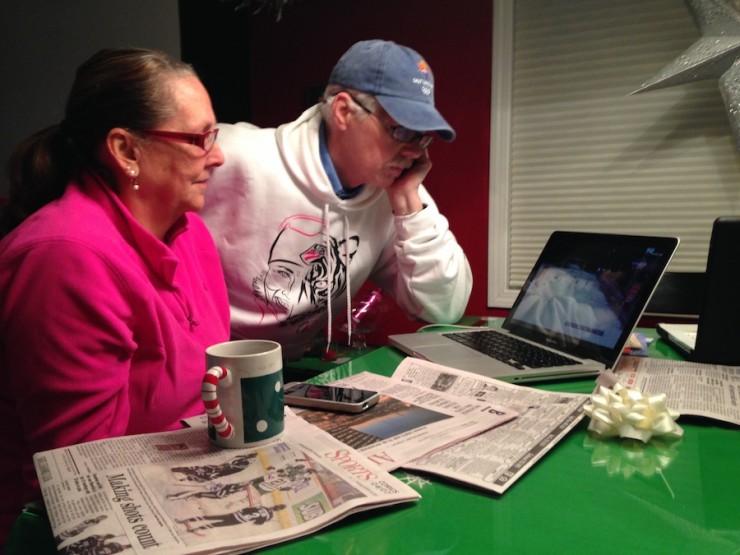

Early Saturday morning, Kikkan Randall’s parents sat groggily in front of a pair of laptop computers in an East Anchorage condominium.

Their 31-year-old daughter was seconds from starting a ski race 5,000 miles away, in a resort town in the Czech Republic. But their live stream of a Eurosport TV channel was showing ski jumping instead.

“OK, come on,” Deborah Randall, Kikkan’s mother, said impatiently.

Kikkan hadn’t competed in three weeks, and Saturday’s race was her first since she’d suffered a back injury 12 days earlier. She was facing tough competition in her sprint heat, and if it didn’t go well, her day could be over after just three minutes of racing.

Justifiably, her parents were nervous.

Finally, the feed switched over, just in time for the Randalls to see their daughter cross the finish line in front of five other women, qualifying her for the next round of sprinting.

It was 6:03 a.m., with another hour of racing still to come. Time for some coffee.

In less than a month, Randall will be contending for a gold medal at the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.

Watching From Afar

Millions of Americans will likely tune in to watch Randall’s exploits on tape-delayed prime time television — just like they do every four years for Olympic athletes.

But for the last three winters, a small group of intensely loyal cross-country ski fans in Anchorage has been following all along.

Friends, family members and even coaches tune in to unpredictable video streams just to catch a glimpse of Anchorage athletes such as Randall and Holly Brooks competing 10 time zones away in Europe. And they do it at midnight, at 1 a.m. or 2 a.m. or 3 a.m., so that they can watch live.

“I always stay up,” said Ronn Randall, Kikkan’s father.

Deborah chimed in: “I would never miss her race.”

On Saturday morning, Deborah was wearing a pink fleece, her daughter’s trademark color. Ronn was wearing a Kikkanimal Fan Klub sweatshirt.

As Kikkan prepared for her semifinal heat, her parents recalled the days before video streaming, when they had to rely on rare cable television broadcasts of snippets of races, or a bare-bones live timing application that would pop up with skiers’ names and times.

Even that was futuristic technology compared to what was available to earlier generations of athletes.

Nina Kemppel, an four-time Olympian from Anchorage who competed internationally during the 1990s and early 2000s, said she used to update a couple dozen of her friends, family and sponsors with spare, text-based emails. Slow Web connections wouldn’t allow for photos.

When there was no Internet, “my parents didn’t know how I raced until I was able to find a phone and dial, $4 a minute, back home,” Kemppel said. “It was a different time.”

Now, Kemppel says, she occasionally joins the ranks of the hardy few who stay up to watch the races. Or, she’ll wake up the next morning to read reports online, or watch footage that’s been archived on any number of websites.

Set Your Alarm

Other avid fans include junior skiers at Randall’s home club, Alaska Pacific University. And friends like Laura Gardner, who used to room with Randall and ski raced with her at East High School.

Gardner described her viewing habits with a mix of enthusiasm and fatigue — especially when recalling how she tuned in to last winter’s Tour de Ski, a stage race that included seven events in nine days.

“I don’t know how I did it,” she said. “I felt like I was doing the Tour de Ski, because it was so many nights of being up at 4 a.m.”

Gardner said that one of her friends is already planning a late-night viewing party for the Olympics. The time difference between Anchorage and Sochi is 11 hours, and most of the races are scheduled between midnight and 5 a.m. in Alaska.

It’s the middle of that time frame that’s the worst, Gardner said.

“There’s no getting up early; there’s no staying up late,” she said. “You just have to set your alarm for the middle of the night.”

Overnight Inspiration

Since she’s been competing, Randall said that the advances in technology have allowed her to stay closer to her family, including her husband, Jeff Ellis.

She cited video, but also Skype, a free application that allows users to video chat.

“I don’t know how skiers did it before, because Skype was essential,” Randall said in a phone interview from Europe, where she was sitting near two other people who were using the application to talk with their families.

The increasing availability of video, Randall added, has raised the profile of her sport.

“When I was a kid in Alaska, I think all I ever saw was what was printed in the paper, and what happened in the Olympics,” she said. “When you hear that a 14-year-old boy somewhere watches your winning race every night before he goes to a ski race the next day, for inspiration, that’s just incredible.”

Remote spectators for Saturday’s race included not just Randall’s parents, but also her coach, Erik Flora, who said he watched from the airport in Salt Lake City on his way back from national championship races.

‘Now, Look at Her!’

Back in Anchorage, Randall’s parents grew more and more tense as Kikkan advanced through the sprint rounds.

“This one’s going to be a real test,” Ronn said, as his daughter lined up for a heat with Norwegian, Swedish and German skiers.

During the final round, Deborah clasped both hands to her face as the women wound their way around a narrow strip of snow.

Midway through the race, Randall accelerated up a hill, leaving a big gap between her and the pack. The British announcers had earlier pronounced her “on fire,” and now they were calling her the Olympic favorite.

“Oh, no way. Oh, my God. Now look at her!” Ronn said.

Deborah jumped and shrieked as Randall crossed the finish line first, racking up a $16,500 paycheck and sending a message that the three-week break hadn’t left any rust.

“Now that’s what I love!” Deborah said.

The family will be reunited in February, when the Randall parents travel to Russia to watch their daughter compete for a medal.

For now, a congratulatory text message from Deborah would have to suffice.

Fifteen minutes later, one came back from the Czech Republic: “Whoopee!”

Nathaniel Herz

Nat Herz is an Alaska-based journalist who moonlights for FasterSkier as an occasional reporter and podcast host. He was FasterSkier's full-time reporter in 2010 and 2011.

One comment

shreddir

January 18, 2014 at 5:08 am

Watching Eurosport when they schedule cross-country after live ski jumping it’s likely you will miss quarter final heats for the women. Only if you look on the schedule and see it’s following a taped event are you guaranteed to see the whole race. The jumping coaches don’t care how much they hold up the live broadcast because they won’t drop their “Go” flag unless they think the wind is perfect for their jumper. It’s usually the fricking Germans or Austrians that do this. Plus Eurosport programming is ruled by corporate advertisers whose main customer/ viewers are fat Germans couch potatoes who only care about ski jumping and biathlon. They could care less about running over cross-country. Now if only we weren’t geo-blocked from watching Norway’s NRK national broadcasts then you would see every single minute without commercials plus in depth interviews. Maybe some decade, ha,ha.