News broke on Wednesday that Norwegian cross-country skier Martin Johnsrud Sundby lost his 2015 World Cup overall title after an anti-doping rule violation (ADRV).

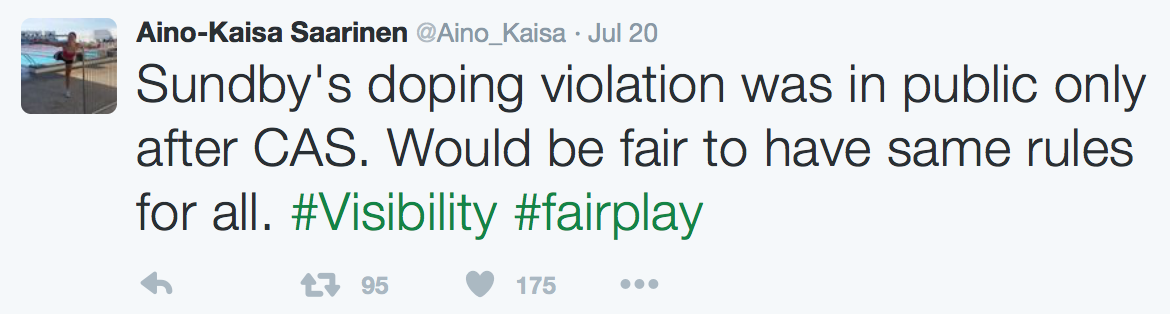

Among athletes and fans, one of the biggest reactions was of surprise: Sundby’s samples had been collected in December 2014 and January 2015, yet the case had never been publicized.

That is primarily because despite the adverse analytical finding (AAF) of salbutamol — a common asthma medication — in two of Sundby’s urine samples, the International Ski Federation (FIS) concluded that he had not broken any rules.

First, because salbutamol is a “specified substance”, according to the WADA Code, FIS was not required to give Sundby a provisional suspension while they resolved his case. Thus he did not miss any races after the AAF’s were reported to FIS.

Then, because the eventual Anti-Doping Hearing Panel conclusion was that there was no ADRV, FIS was also not required to publicize the result – in fact, they could not publicize it at all without Sundby’s consent, which he did not provide.

“FIS and the Norwegian Ski Association have followed the regulations and procedures as provided for in the FIS Anti-Doping Rules and WADA Code concerning communication of the decision of the FIS Doping Panel,” FIS Secretary General Sarah Lewis wrote in an email to FasterSkier.

Confidentiality is oft-discussed and highly prized according to FIS Rules. Thus only after the Court of Arbitration for Sport supported an appeal by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and ruled that an ADRV did occur, was FIS required to publicize the case.

Why No Rule Violation?

One common circumstance where an AAF can lead to no rule violation is if an athlete has a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE) for the substance in question.

Although he has long discussed his asthma diagnosis, Sundby did not have a TUE for salbutamol because he believed he didn’t need one.

As a class of drugs, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) prohibits the use of beta-2 agonists, with the following exceptions (as described in the 2015 Prohibited List):

“Inhaled salbutamol (maximum 1600 micrograms over 24 hours);

Inhaled formoterol (maximum delivered dose 54 micrograms over 24 hours); and

Inhaled salmeterol in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommended therapeutic regimen.

The presence in urine of salbutamol in excess of 1000 ng/mL or formoterol in excess of 40 ng/mL is presumed not to be an intended therapeutic use of the substance and will be considered as an Adverse Analytical Finding (AAF) unless the Athlete proves, through a controlled pharmacokinetic study, that the abnormal result was the consequence of the use of the therapeutic inhaled dose up to the maximum indicated above.”

Sundby’s urine samples both had over 1300 ng/mL of salbutamol, triggering an AAF and beginning the investigative process into whether he had an appropriate TUE.

He didn’t, based on advice of a team doctor. The reason — that he was taking the medication through a nebulizer rather than an inhaler and believed that this made a TUE unnessecary — was explained in a previous article.

“We know the rule for use of the the nebulizers now and we will not do the same mistake again,” Norwegian men’s coach Tor-Arne Hetland told FasterSkier in an email. “We will for sure ask for a TUE one extra time instead of one too little in the future. Martin would have gotten a TUE if he asked for it. To get a TUE happens quickly, but the decision is made separately in each case.”

Most people don’t consider the use of the salbutamol to be performance-enhancing. Doctors and medical researchers have concluded that salbutamol is not ergogenic for athletes who are not experiencing constricted airways through asthma or exercise-induced bronchiospasm.

“The net effect for anyone whom does not have [exercise-induced bronchiospasm] is negligible: you can’t relax smooth muscle in the airway if it has not been contracted,” Dr. Michael Kennedy told FasterSkier in January, referring to the drug’s mode of action.

Numerous studies have backed this up, showing that giving asthma medication to athletes does not improve performance in time trials or races.

None of this changes the fact that WADA prohibits inhalation of the drugs in high concentrations, or via injection or ingestion. And salbutamol is also banned because it is a masking agent – that is, it could be used to hide the presence of another performance-enhancing drug.

In the “masking agents” section of the Prohibited List, the organization writes that “The detection in an Athlete’s Sample at all times or In-Competition, as applicable, of any quantity of the following substances subject to threshold limits: formoterol, salbutamol, cathine, ephedrine, methylephedrine and pseudoephedrine, in conjunction with a diuretic or masking agent, will be considered as an Adverse Analytical Finding unless the Athlete has an approved TUE for that substance in addition to the one granted for the diuretic or masking agent.”

One might expect that after an AAF, an athlete would be provisionally suspended. But according to FIS Rules, that was not necessary.

No Provisional Suspension

FIS rules about confidentiality are clear. In the early stages of a case, only those who “need to know” should be told about it, according to the rules. For instance, from the 2015 Anti-Doping Rules: “FIS shall ensure that information concerning Adverse Analytical Findings, Atypical Findings, and other asserted anti-doping rule violations remains confidential until such information is Publicly Disclosed in accordance with Article 14.3.”

If a case makes it into the media at this point, it is usually because it has been publicly announced by the athlete or their national federation, or else leaked by someone else who has inside knowledge.

“Information sometimes reaches the public domain since the athlete or person defending an anti-doping rule violation is communicated during the course of the proceedings,” FIS Secretary General Lewis wrote. “This has not been the case this time.”

It could have been obvious that something was going on if Sundby had disappeared from the World Cup based on a provisional suspension. But he didn’t, because salbutamol does not lead to a mandatory provisional suspension.

According to Provision 7.9.1 of the 2015 FIS Anti-Doping Rules, only athletes who have tested positive for a drug which is not a “Specified Substance” must receive a provisional suspension. Provision 7.9.2 states that for drugs which are Specified Substances, a provisional suspension is not mandatory.

“7.9.1 Mandatory Provisional Suspension: If analysis of an A Sample has resulted in an Adverse Analytical Finding for a Prohibited Substance that is not a Specified Substance, or for a Prohibited Method, and a review in accordance with Article 7.2.2 does not reveal an applicable TUE or departure from the International Standard for Testing and Investigations or the International Standard for Laboratories that caused the Adverse Analytical Finding, a Provisional Suspension shall be imposed upon or promptly after the notification described in Articles 7.2, 7.3 or 7.5.

7.9.2 Optional Provisional Suspension: In case of an Adverse Analytical Finding for a Specified Substance, or in the case of any other anti- doping rule violations not covered by Article 7.9.1, FIS may impose a Provisional Suspension on the Athlete or other Person against whom the anti-doping rule violation is asserted at any time after the review and notification described in Articles 7.2–7.7 and prior to the final hearing as described in Article 8.”

What is a Specified Substance? WADA’s 2015 Prohibited List defines those as all substances except: anabolic agents, peptide hormones, growth factors, and related metabolic substances and mimetics, anti-estrogenic substances, agents modifying myostatin functions, and some stimulants.

As a beta-2 agonist and masking agent, salbutamol does not fall into any of these categories.

“Salbutamol is a Specified Substance,” FIS Anti-Doping Administrator Sarah Fussek wrote to FasterSkier in an email. “Therefore a provisional suspension is not mandatory.”

FIS did not opt to give Sundby a provisional suspension through Provision 7.9.2, either. Instead, they asked him a series of questions about his use of the drug, consulted an Australian expert, and then sent his case to an Anti-Doping Hearing Panel. During this time, Sundby continued to compete.

The way that FIS handles public disclosure of ongoing cases is notably different than that of some other federations. The International Biathlon Union (IBU), for example, releases information on provisional suspensions when “A” samples test positive for prohibited substances, but do not include the name or nationality of the athlete. Here’s an example.

Why Wasn’t Sundby’s Case Made Public?

The Anti-Doping Hearing Panel concluded, as previously described, that no ADRV had occurred – partly because it deemed the WADA Prohibited List’s language unclear as to whether “inhaled” referred to the specific method of use, i.e. from an inhaler, or the general method of consumption, i.e. inhalation versus injection or ingestion.

At this point, FIS was constrained by its own rules as to whether it could publicize the case.

If a hearing panel determines that no ADRV has occurred, FIS can only publicize the case with the athlete’s consent, according to Provision 14.3.3:

“In any case where it is determined, after a hearing or appeal, that the Athlete or other Person did not commit an anti-doping rule violation, the decision may be Publicly Disclosed only with the consent of the Athlete or other Person who is the subject of the decision. FIS shall use reasonable efforts to obtain such consent. If consent is obtained, FIS shall Publicly Disclose the decision in its entirety or in such redacted form as the Athlete or other Person may approve.”

This language is similar to that of rules from FIFA, soccer’s governing body.

“After the decision of the FIS Doping Panel, the decision not to communicate the decision is the prerogative of the athlete, and yes FIS officially made this request to the athlete and Norwegian Ski Association in accordance with the FIS Anti-Doping Rules and WADA Code,” Lewis wrote.

After the CAS decision asserted that an ADRV had in fact occurred, the situation changed. FIS must report the final result of an appeals case — or three other types of cases, included those where the athlete does not challenge that a rule violation has occurred — within 20 days.

That’s in keeping with language in the Anti-Doping Rules of some other international federations, for instance the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI). The language in the rules of the International Judo Federation (IJF) and International Swimming Federation (FINA) are identical to the FIS rules, down to the numbering of the relevant articles in section 14.3.

Sundby, who has vigorously defended himself in the press once the case went public, clearly wanted it to stay private. One can assume that’s why he opted not to go public after he was initially vindicated by the FIS Anti-Doping Hearing Panel.

“Reactions in Norway have been on different levels positive for Martin,” Hetland wrote. “The athletes in the team and from the other sports support him, the federation support him, sponsors for the federation and for Martin support Martin [and the federation] and media that have read and understood the case support Martin. Of course some media ask questions… The case is hard for Martin. He takes his punishment and [is] looking forward to get back to training with the team again.”

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.