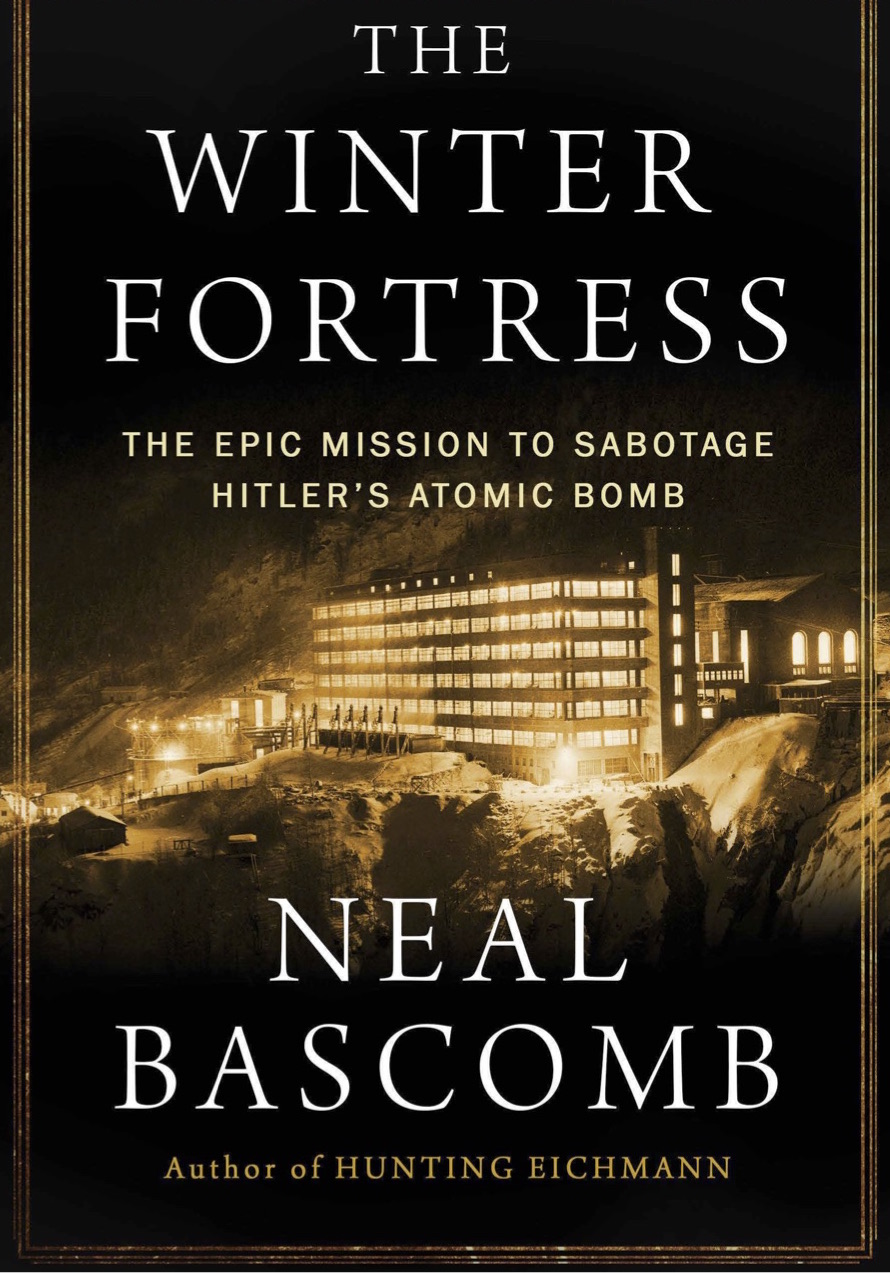

Biathlon, like many Olympic sports, began as a way for soldiers to practice their skills. Neal Bascomb’s new book, “The Winter Fortress”, tells the tale of Norwegian and British soldiers on skis fighting the German occupation of Norway in World War II.

The pressure of getting that fifth target at World Championships is nothing compared the feeling one had while trying to shoot down a German skier before he led an entire German troop to a hidden commando team.

“In a staggered line, the nine saboteurs cut across the mountain slope. Instinct, more than the dim light of the moon, guided the young men. They threaded through the stands of pine and traversed down the sharp, uneven terrain, much of it pocked with empty hollows and thick drifts of snow. Dressed in white camouflage suits over their British Army uniforms, the men looked like phantoms haunting the woods. They moved as quietly as ghosts, the silence broken only by the swoosh of their skis and the occasional slap of a pole against an unseen branch. The warm, steady wind that blew through the Vestfjord Valley dampered even these sounds. It was the same wind that would eventually, they hoped, blow their tracks away.” — an excerpt from “The Winter Fortress”

Although the book details the excitement of handgun-on-skis battles between Norwegians and Germans, Bascomb also tells the larger tale of the struggle to keep German scientists from building nuclear weapons. By using individual diaries, the author is able to bring life to a multi-country effort that dramatically changed the course of international relations.

Many history books are, to put it kindly, boring. This book embeds the history on a narrative thread of battles, family dilemmas and personal struggles. The international politics, battles with bureaucracy, hardships of bivouacking in the snow, chemistry of bomb making, and weather-induced failure of major operations are all there, neatly woven into a story that keeps the pages turning.

The importance of this story is in it’s historical context. Before World War II, German scientists had proposed the possibility of nuclear weapons. By 1944, Germany was using rockets to bomb London with conventional explosives. If Germany had been allowed to use their head start to complete a nuclear weapon, it is very possible that the U.S. forces (overpaid, oversexed and over here) would never have reached continental Europe. Because the Allies were able to control the world deuterium supply, the U.S. was the first to develop the atomic bomb (demonstrated with horrifying effect in Hiroshima and Nagasaki). A secondary effect was that German rocket scientists like Werner von Braun did not become war criminals and were able, after their capture by U.S. forces at the end of the European war, to build the Apollo rockets that put Americans on the moon.

The book has current interest as well. Bascomb details the individual decisions to use extraordinary rendition (a.k.a. torture) and to bomb civilians for the greater good. As the events occurred 70 years ago, the author can review the reasoning and the results with the help of diaries and documents from both the Allies and the Axis powers. Although Bascomb is careful to avoid taking sides, the documented evidence clearly shows the effectiveness and cost of stepping outside the Geneva Conventions.

This book is interesting, historically accurate, scientifically accurate, and well written. Even without the skiing, this would be my favorite nonfiction book of the year.

I asked the author why he chose this story. There is a more polished and professional explanation on his website, but his direct response better reflects his passion for history:

“There is always what intrigues me about a story, then what drives me to spend three or more years researching and writing a book.

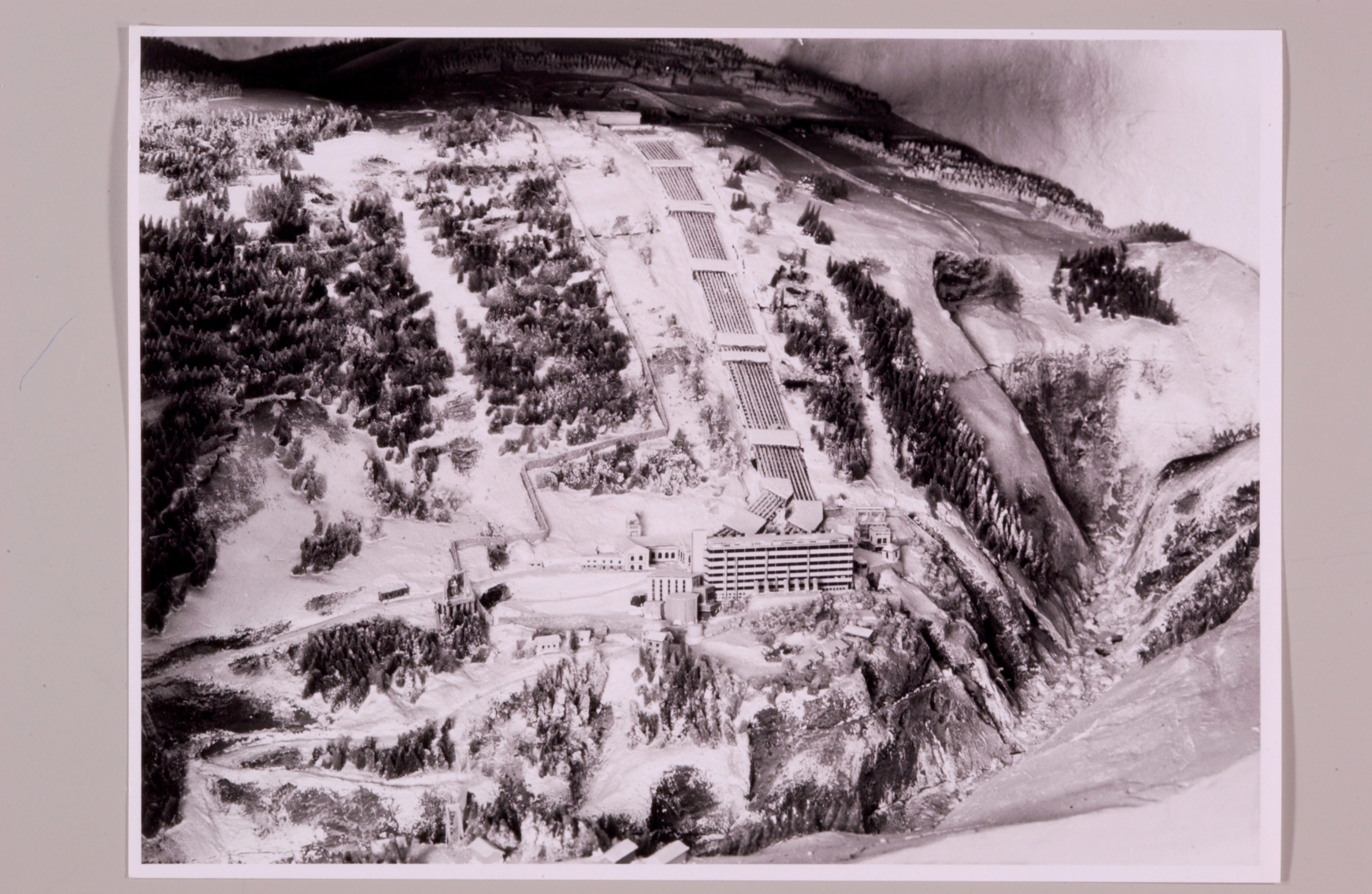

For THE WINTER FORTRESS, the idea of spies on skis surviving out in the wild for months on end before infiltrating a heavily guarded plant (Vemork) that holds the keys to the German atomic bomb program hit me on three levels. I love science history. I love spy stories. And I love survival and adventure. This story combined all three.

That said, I did not know I wanted to pursue this as a book until I learned of Einar Skinnarland. He was born on the edge of vast mountain plateau in Norway that is snowbound for many months of the year. He learned to cross-country ski as soon as he did walk. Before the war, he was studying to be an engineer, and he had no military experience. Suddenly, the Germans invade, occupy his country, and he wants to fight. He hijacks a steamer on the coast and crosses the North Sea to reach England. He wants to be trained to fight. Instead the Allies and Norwegian Army command see an opportunity in [him]. He is from the area around Vemork. If he returns home quickly, nobody will know he had gone to England. So they give him a week to learn how to parachute, and he is dropped back into Norway to spy on Vemork and prepare for an operation against it. Here is this student who suddenly becomes a spy, and for the next three years, he endures a double life, then constant manhunts, surviving out in the woods, skiing a marathon’s distance almost every day to deliver intelligence or supplies to the sabotage party. He cuts such a remarkable figure, and I had access to his daily diaries, access to how he managed his long struggle, how it affected him. Once I had Skinnarland (and his handler Leif Tronstad, a scientist turned spymaster), I knew I had to write this book.”