Where I’m going the day after the Birke

I know what you do the day after the Birke. Linger in bed. Go online to look at your time. Compare it with that other guy in your ski club’s time. And that other guy. Figure out if you were fast enough to move up a wave next year.

But this year there’s another option. You could drive a few hours west to Lake Itasca State Park in Minnesota and climb back into your boots and join in something novel: a nordic ski protest against the proposed Line 3 tarsands pipeline. Ski the Line they’re calling it, and if you ask me it’s a way to pay back winter for all it’s given us.

The 15 k ski along part of the proposed route of the pipeline is a stand against inevitable leaks and oil spills, and against the continued subjugation of native Americans. And, crucially, against the ongoing disruption of the planet’s climate. Line 3 is, like the Keystone or Dakota Access pipelines, the classic example of something that should never be built again. Theoretically a “replacement” for an existing pipe built in 1961, it’s much larger in volume and cuts across a new corridor—in fact, at 915,000 barrels of oil a day it would be one of the biggest pipelines on earth.

And it would carry the dirtiest oil on earth—the tarsands sludge from the wastelands of Alberta’s once-grand boreal forest. A large-scale study made clear in 2015 “that any increase in unconventional oil production” (which is to say tarsands oil) is “incommensurate with efforts to limit average global warming to 2 °C” (which is to say, keep building these things and it’s game over for the climate.)

Ski the Line is being organized by Honor the Earth, a remarkable nonprofit headed by the equally remarkable Winona Laduke, from the Ojibwe White Earth reservation in Minnesota. She’s made the case that the pipeline violates not only tribal sovereignty, but also the “usufruct” rights granted the tribes when they were forced off their land. “Pipelines threaten the culture, way of life, and physical survival of the Ojibwe people. Where there is wild rice, there are Anishinaabeg, and where there are Anishinaabeg, there is wild rice. It is our sacred food. Without it we will die. It’s that simple.” And when pipelines leak, as they inevitably do, there goes the water—just ask the people of Kalamazoo, where the river still hasn’t fully recovered from a 2010 tarsands pipeline spill.

But even when oil reaches the refinery without leaking, it spills into the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide. These pipelines are like giant straws sucking the carbon out of Alberta and pouring it into the air: if all the economically recoverable oil in the Canadian tarsands was burned, the atmospheric concentration of CO2 would grow from its current 410 parts per million (already much too high) to 540 parts per million. Just from this one oilfield—it’s an emergency.

After years of local organizing, most local government officials came to agree that the plan was a bad idea: the Minnesota Department of Commerce officially found there was no need for the project, and recommended not granting it a permit. But the state’s Public Utilities Commission approved the plan last summer, and so it’s likely to proceed unless people stand up in even greater numbers.

Which is where Nordic skiers come in. For most people, 15 kilometers through the Minnesota woods is a long trek, but for people who just skied the Birke, it’s a cooldown. We’re able to go see the facts on the ground and to help spread the word. Yes, it will take a tank of gas to get there. But it will be the most useful carbon you burn all year.

I’ve watched too many snowstorms turn to slushy rain the last few years. (And watched the destabilized Arctic send us an occasional blast of the polar vortex too, a few days of temps too cold to ski.) I love the winter that humans knew throughout the Holocene, the season when friction disappeared. I love it enough to crawl out of my bed the day after the Birke and do what needs to be done. I hope you do too. As the Ojibwe say, Miigwech!

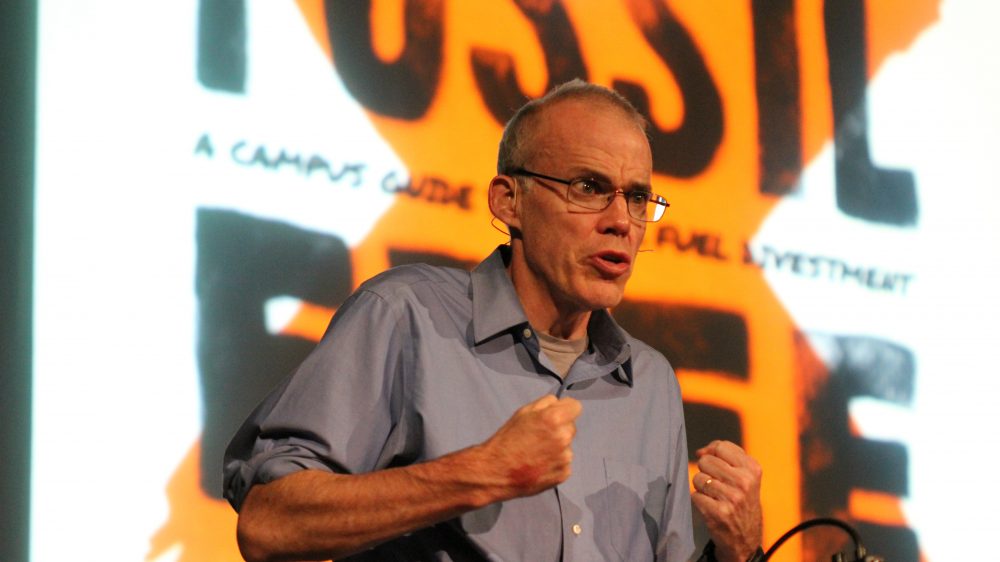

You can register for Ski the Line here. Bill McKibben is a founder of the environmental group 350.org, and the author of, among many other books, Long Distance: A Year of Living Strenuously about his adventures as a slow cross-country ski racer.

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.