Editor’s note: We are thrilled to have John Wood start off our new series here at FasterSkier, “Letters to my younger self.” Lauren Fleshman provided the modern locus classicus for this genre, and John has written a superb, ski-specific first installment for this site. He sets a pretty high bar, but the general theme of this series is clear: If you were writing a letter to your younger self, what would you want to tell them about skiing, life, or skiing and life?

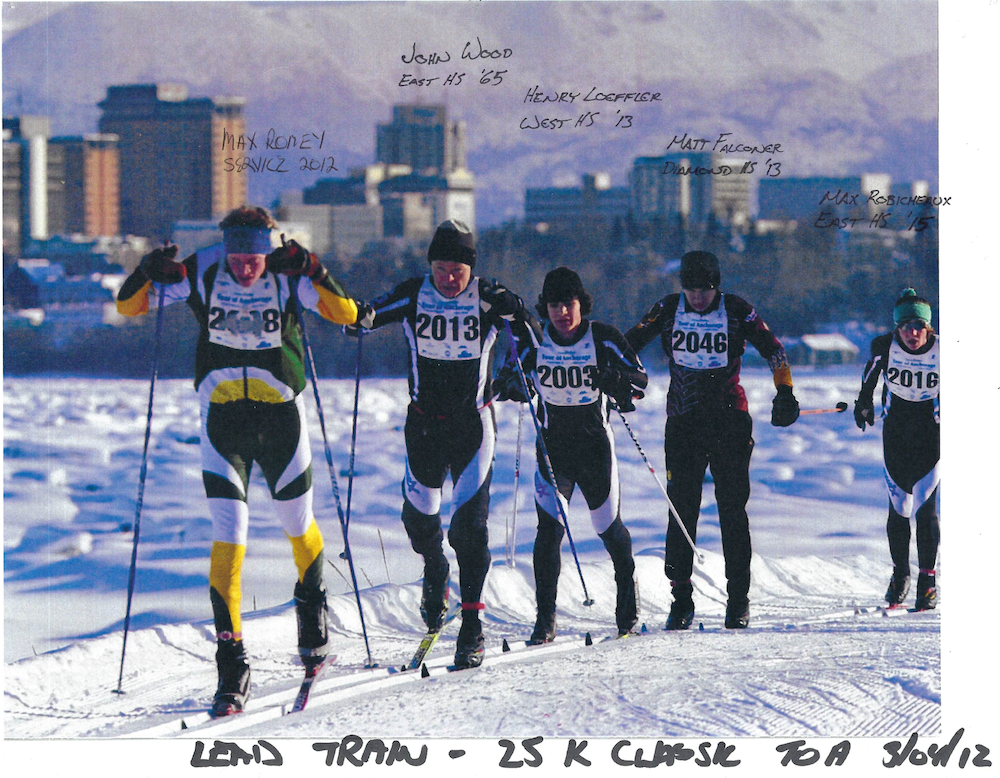

John Wood has been an Alaska resident since age 11. He is an age-group champion in the American Birkebeiner (first out of 112 men in the 65–69 division of the 55-kilometer classic race a few years ago), and is a multiple-time age-group winner in just about every ski race in southcentral Alaska. At the 2019 World Masters Cup in Beitostølen, Norway, John was the top American in his age group in every race, including an 11th-place finish, out of roughly 100, in the fiercely competitive M9 15k classic. The photo that he submitted for this article of the 2012 Tour of Anchorage 25k classic (above), in which he is going head to head with athletes 50 years his junior in a race where he finished fifth out of 304 overall, represents #lifegoals for masters athletes everywhere.

The other athletes mentioned in this essay constitute a who’s who of Alaskan skiing. Dick Mize was a 1960 Olympian in biathlon, a two-time NCAA nordic team champion, six-time World Masters champion, and did more than anyone else to help bring Anchorage’s world-class trail system into existence. Tom Besh would go on to ski on the U.S. Ski Team, be the first full-time ski coach for the University of Alaska Anchorage, and found numerous races that still exist, including the iconic Crow Pass Crossing. The modern-day Alaska JOQ races, Besh Cups, are named after him. Jim Mahaffey founded the nordic teams at University of Alaska Fairbanks and what is now Alaska Pacific University, the Tuesday Night Race Series in Anchorage, and the Equinox Marathon in Fairbanks, after arriving in Anchorage in 1950. He coached at least six Nordic skiing Olympians. The APU campus trail system is named after him. Mize and Mahaffey, now in their 80s and 90s, respectively, are still alive; Besh died in a small plane crash in 1993. John lives in Eagle River, Alaska, outside of Anchorage.

By John Wood

I just finished reading FasterSkier’s brilliant interview with Greta Anderson. A karma flowed from this wonderful article and distant memories of my high school and early college days in the 1960’s begin to wash over me and I began to write:

Building a successful cross country skier takes time and vision, the willingness to set goals, then work for intermediate milestones on the way to the ultimate goal.

Building a successful cross country skier takes patience, the patience to work through bad days, sickness, subpar results.

Building a successful cross country skier takes more than natural ability. A successful skier needs an intense desire and single-minded dedication to succeed, have the discipline to forgo late nights with associated “extracurricular” activities, and have or develop the ability to organize so there is sufficient time for class, studies, training and rest.

Building a successful cross country skier takes a support team that starts with parents and family then extends to coaches, friends, club and community.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, success in skiing is just as much about the journey and “enjoying the ride” as it is climbing to the top of the podium.

* * *

In the beginning (1962), I was a runty little high school freshman in Anchorage, Alaska. My family had been living on a remote homestead and I had been homeschooling for several years and had few friends. We had just lost all of our personal possessions in a disastrous fire that totally destroyed our homestead home. Our family had a hard time making ends meet and my paper route supplied most of my clothing money and all of my spending money. Plus, most of the other students in my classes were growing and I wasn’t! I wasn’t shy, but I definitely was not very athletic.

Then something changed… in 1964 during my junior year I had Dick Mize for a P.E. teacher. I also started to grow… YAY!! I turned out for the hockey team, but soon switched to the cross country ski team because I was so inspired by Mr. Mize, who was also the ski coach. I knew nothing about skiing other than my neighbor, Tom Besh, was on the team and he talked about skiing all the time. For $5 I bought a pair of GI “white elephant” skis and cut them narrower to a profile that I traced from Tom’s race skis. My athletic ability blossomed with my height and by the end of the season I was consistently the fifth man on the East High school ski team.

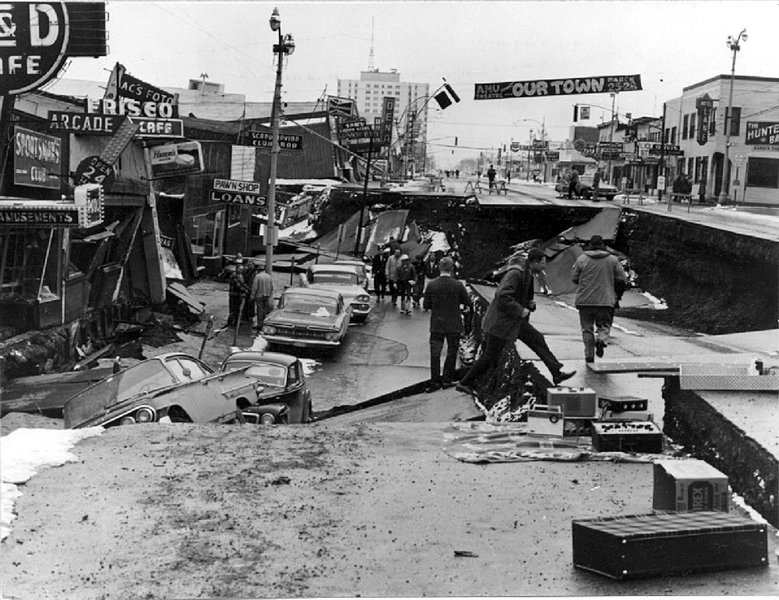

The March 27, 1964, Good Friday (magnitude 9.2) earthquake hit just after the ski season completed and really shook things up in southcentral Alaska. As the months went by life slowly returned to normal; the highlight of the summer was when Tom and I, at the last minute, signed up and raced in the very first Junior Mount Marathon race, where I placed fourth. [Tom would go on to win the 1965 junior race, and the senior race three times.]

During my senior year in 1964-65 my skiing continued to improve, and I was third in the state meet and was a member of Alaska’s second full Junior National team, competing in Bend, Oregon. By this time, skiing and running had become second nature to me and I expected to be in the competitive mix every time I approached the start. I had risen to the top echelon of the Alaska junior talent pool.

Success began to come easily, perhaps too easily. I could ski hard during the day, dance and party hard at night, and wolf down an occasional meal between activities. I was taking advanced “college prep” courses and didn’t need to study much in order to make decent grades (B average). In retrospect, I was not developing good life habits necessary to sustain any kind of a career in collegiate skiing.

After high school graduation I worked as a laborer for a company that made concrete precast manholes that were used to help replace the sewage systems damaged by the earthquake. I worked hard all day and caroused till late at night. Skiing was far from my mind, even though a lot of my friends entered and placed at the top of the Junior Mt Marathon race that summer. According to my father, college was for study and any extra time was for work so you could scrape enough money together to pay for the next semester. Sports were for losers who were not academically preparing themselves for being gainfully employed, and “everybody knew” these young men were headed for the Army.

Well, in the fall of 1965 I only had enough money to attend the local college, Alaska Methodist University (“AMU”), and live at home. So I became an undisciplined college freshman trying to participate in all the wonderful new activities available at college while continuing to work part time at the precast shop. About this time something else happened. We were required to take a P.E. class during the fall semester, and I took cross country running along with the basketball team members (the only organized intercollegiate sport at AMU). I was beating those guys by minutes in our time trials, and I was approached by the instructor and asked if I wanted to ski cross country for AMU, even though they didn’t yet have a team or coach. So, driven by my love of skiing, I started to train by myself with no plan or goals or sponsorship.

I won most of the local Junior races till the end of January, when my too-busy lifestyle and a lingering illness combined with overtraining caused my results to slide precipitously. I was physically beat and mentally flamed out. I quit training and finished the school year on a real down note.

After the end of the semester I got a job in the mountains on a BLM cadastral survey crew for the summer. We worked eight hours per day, six days per week, and my job was to operate a large chainsaw and clear the trees and brush so the instrument man could have a clear view down the survey line and the distance measurers (chainmen) could measure the distance. Operating a large chainsaw while hiking up and down the mountains every day made me really tough!

The summer flew by and in early September I was off to the University of Alaska in Fairbanks to study Mining Engineering. Mining engineering was and still is a very difficult major that combines aspects of engineering principles, geology, and mining-specific engineering with a heavy dose of upper mathematics and mineral preparation. That first year my mornings were filled with classes and afternoons with three-hour “labs.” Due to a class conflict I had no lab on Wednesday but had one on Saturday morning. Not much time for anything but attending class and study.

I made a lot of new friends and one of them who knew my athletic background bet me that I couldn’t run the Equinox Marathon that’s held annually [in Fairbanks] in mid-September. Even though I hadn’t run a step for many months (other than fast hiking in the mountains most days at work to get to where we had finished the night before), I felt strong and thought I had it in me to run the entire distance – 26+ miles that includes running up and down Ester Dome twice.

On race day I laced up my ROTC canvas Converse tennis shoes and stepped to the starting line behind what looked to be the fast runners. Off they went at the gun, and I followed behind in the masses at a fast jog. After a while, I felt my body dropping into its familiar mile-eating pace so I allowed myself to “open it up” and started to pass hundreds of runners. Up Ester Dome and down the other side, turn around and back up again. At the top somebody told me I was in the top 10, and I was so excited that I bounded down the Dome.

At the bottom there were a few more miles to go, and all of a sudden I felt really tired. During the summer work I had trained myself not to drink during the workday but to take lots of fluids in the morning and when I returned to camp at night.

I had not been taking any fluids at the aid stations; I had never been in a race where they were offered.

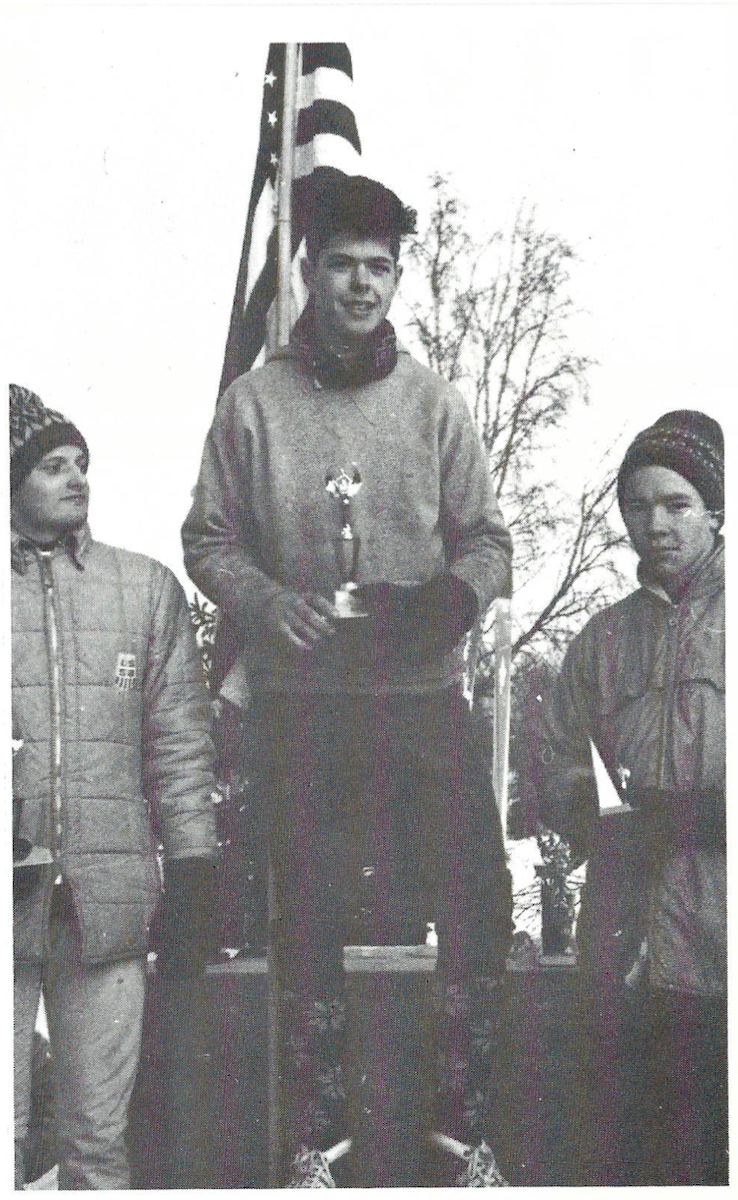

But with about three miles to go I was so thirsty that I had to have fluids, so I drank a glass of sugar water. Bad move, it came right back up, I got the dry heaves, and it was all that I could do to keep running and keep putting one foot in front of another. I did pass another competitor just prior to the end and found out I finished fifth overall! The small stainless steel engraved candy dish trophy for fifth place is my most cherished athletic possession.

I really felt good about myself and after I recovered from the race effort I tried to turn out for the ski team. I could only train on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons, and I soon became disheartened, lost interest, and dropped out.

In 1968 I decided to spend the summer in Anchorage and got a job surveying. I ran into a couple of old ski friends who were off-season training for Mt. Marathon, and they talked me into running the race with them. I trained for about three weeks and got ninth place! (After not running or training since my Equinox Marathon days some 20 months previously.) Well, fresh from that most positive experience I decided to train for the rest of the summer and try to win the Equinox Marathon that fall. Trouble is, when I was playing soccer about three weeks later, a week after my 21st birthday, I experienced a major tear of the medial meniscus in my right knee and ended up having surgery after experiencing a “locked knee.” I have never been able to run another competitive running race.

Some of the guys and girls that I knew from high school and AMU that stuck with skiing in college and trained during the summer became either NCAA All-Americans or Olympians, or both.

Me, I just couldn’t get my athletic life together beyond an occasional flash of brilliance.

* * *

Fast forward 39 years (1968–2007). I had been living a comfortable, if somewhat sedentary typical middle class Alaskan lifestyle, interrupted by occasional periods of regular physical activity. The Iditarod dog team was gone by the middle of 1986 and our children had left home and begun careers of their own. [Note that John’s “typical” and “sedentary” lifestyle included finishing the Iditarod sled dog race four times between 1978 and 1986. Also, within this period the school formerly known as Alaska Methodist University had renamed itself as Alaska Pacific University. – Ed.]

So when I turned 60 I decided to treat myself to a winter “subscription” to the Alaska Pacific University Nordic Ski Center (APU) masters ski program, which provides top-notch coaching that tailors modern cross country ski training methods to the older bodies of masters skiers. I thrived and finally felt in my element. I was able to enjoy the big picture athletic preparation and feel good about the “whole me.” My coaches and fellow master skiers were, and continue to be, great and plain-ol nice people and a real pleasure to be around.

It is now 2021, I am 74 years young and have lived a full life with a successful career. I have no regrets, wouldn’t change a thing in my life, and have always tried to make the best with the hand of which I was dealt. I have been married for 52 years to my wonderful wife Cathy, whom I met in structural geology class at college. She continues to be my “reality check” and is the steadying influence on our extended family. Any excesses that I may have indulged in during my younger years have now disappeared in my rear view mirror.

Sooooo, after 13 + years with the APU program and the numerous age-group competition successes that flowed (for example see my two previous FasterSkier articles, “Life at 71 on Two Artificial Knees: 2019 World Masters” and “From a Bum Knee to a 2015 Birkie Age-Group Win”), if I could reach back in time and advise my former self as a young man living in a parallel universe 56 years ago, the advice that I would offer contains many of the elements that I would give to my grandchildren now:

“Kid, don’t think you know it all, ’cause you don’t! You have just graduated from high school, are full of yourself, and are headed somewhere to college. What do you want to do for a job for the rest of your life? Not sure? You can either enter college as “undeclared” or take a flier on a major and change if you find that’s not you.

Do you want to ski in college? First you need to do a “gut check” and ask yourself if you really want to commit to being the best skier you can be, at least till after college. If the answer is “yes” then you need to come up with a plan to get through college while competing and training in a year-round program while not getting drafted into the military and going to Viet Nam. Finally, you need to convince your parents that you have a plan that will work and it’s the best thing for you and everything will turn out just fine and you will be successful in life. The best way for them to show that they love you is to let you stick to your plan!

Well, you have decided to go to engineering school and ski, and you don’t have any money other than what you make in the summer and part-time work at school. There are no ski scholarships at any colleges that I know of, and few schools that offer mining engineering and intercollegiate skiing that you can afford, so that limits the choices to exactly one, the University of Alaska (Fairbanks). Don’t try to get through in four years, plan on taking five or six. Take fewer classes per semester so you have time for some part-time work as well as time to train and recover.

Since all eligible age males that are not full time students are now getting drafted into the military (and headed for Viet Nam), you will need to have a plan up front for your military service. Several options to explore immediately are:

- Take ROTC for four years in college, but before committing determine if you can put off active service until after the extra year(s) needed to graduate. Contact your old friend Sven Johannsen, the USA Biathlon coach at Fort Richardson, and tell him you will take him up on his offer to “get you onto the Biathlon Team” after graduation, or before if you get “drafted” in your fifth or sixth academic years. Alternatively, if you decide you want to, go to Viet Nam and “give ’em hell”. There is always the possibility the war will be over when you are ready to serve.

- Talk to the National Guard. Some of your friends have signed up and find that they have been able to serve locally and can continue their college education with only a few interruptions.

Commit to being a student athlete once you have sorted out your college and military plan. Have single-minded dedication to school and skiing and don’t fill your cup too full. Be happy and have fun with what you are doing and be frugal with your money … you are barely scraping by. Save regular late-night carousing and extracurricular activities for later. I know it doesn’t seem like it, but there will be plenty of time for that after graduation. And who knows, once you have achieved a track record of academic success you might be able to garner those valuable academic scholarships that helped your parallel universe self to stay in school and graduate.

Finally, when you are older you will find that you will look back upon college with fond memories. You got an education and prepared for a career, you got to ski on the collegiate ski team with its associated travel to the United States for competition, you learned how to live a balanced life while having a ton of fun, and you made friendships and memories that will last a lifetime. Trust me, these things are priceless and can never be replaced.”

If you are interested in submitting a letter to your younger self, please contact us at info@fasterskier.com with questions or for more information. We envision providing submissions with light editing for clarity and house style, but not making significant substantive changes. Don’t be scared by John’s credentials; we’d love to hear from you even if you’re not one of the best age-group skiers in the country!

Gavin Kentch

Gavin Kentch wrote for FasterSkier from 2016–2022. He has a cat named Marit.