There’s a great scene in the 1983 classic movie epic The Right Stuff, where the test pilots are hanging out in their dank watering hole discussing the future of supersonic flight and bemoaning what they see as misplaced priorities. The press liaison throwing back a beer with Chuck Yeager and Jack Ridley seems to innocently ask, “you know what makes your rocket planes fly?” The aeronautical engineer puts down his beer and responds by beginning to recite the complexities of aerodynamics when the liaison interrupts, shaking his head at him and says, “Funding, that’s what makes your ships go up. I’ll tell you something …no bucks, no Buck Rogers.” It was a perfect synopsis with a crystal clear meaning. All of the science, bravado, and tenacity in the world didn’t matter if there wasn’t the funding to support the incremental gains needed to push human flight in supersonic speed aircraft. No bucks, no Buck Rogers. It’s that simple.

The same is true in elite level skiing. All the hard work, talent, training, and determination in the world won’t matter if there aren’t the dollars to get athletes to the World Cup, and equally important, to develop young athletes who fill the pipeline on their way to the top of their sport. In short, no cash, no Cups. The best skier in the world can’t win anything on any level, if they’re grounded in their gym in Utah.

This presents skiers with a real problem. In the United States, Nordic skiing is a low profile sport, and unlike almost every major international competitor, the U.S. cross-country squad doesn’t receive direct funding from the government. Contrast that to Norwegian skiers who really don’t have to worry about where the money will come from. Ski fast and the cash will follow. In America, it’s a different story. While the headline skiers on the United States A and B teams receive funding from U.S. Ski and Snowboard, through the U.S. cross-country team, skiers working their way up the skiing ecosystem are largely on their own financially. It takes a mix of club support, sponsorships, fundraising, and donors to keep the pipeline of young talent flowing in the ski game.

If you’re a talented young athlete, you also probably have other options besides skiing. Look at Sammy Smith and Sophia Laukli. Both have the talent to earn a living in other sports. To keep them in the ski game long enough to reach the A team, there needed to be a funding mechanism to help developing skiers until they reached the level of receiving national team support.

For a young skier trying to stay with the sport, the different pieces of the funding puzzle can be an economic Rubik’s cube to try and figure out. That’s where the NNF (National Nordic Foundation) comes in. It acts as the bridge in that funding gap between established U.S. cross-country team skiers, and those without full national team financial support who are chasing their World Cup dreams. It’s the bridge to where the funding is easier to acquire— being an A or B team member of the U.S. national squad— and wandering the financial wilderness of being a developing athlete.

The NNF is a non-profit funded solely by donations whose mission is to “power the opportunities that bridge the gap to World Cup and Olympic excellence for Nordic skiers from the United States.” Chairperson of the Board of directors, former Olympic cross-country skier Laura McCabe—mother of current U.S. team member Novie—states in her letter to the ski community that the NNF was “founded on the belief in supporting a development system rivaling any nation, a vision we’re proudly realizing thanks to our dedicated community.” That founding vision was a tall order considering that the other major Nordic nations don’t have to go to donors with hat in hand soliciting support.

But the NNF has been successful in fulfilling its mandate as a funding bridge. Last year, the NNF raised $470,000 to support the development of the cross-country racing ecosystem in the United States.

NNF uses that money to help skiers afford the cost of winter and summer events and training. In the summer, NNF helps offset the cost of attending training camps. There are National Elite Groups, Regional Elite Groups, National U16 Camp, and international development exchanges and trips. Last year NNF provided over $88,000 in funding for these activities.

During the winter, NNF provides funding for coaching development as well as athlete funding to help attend U18 championships, Junior World/U23 championships, World Cup races, and OPA Cup racing (a second level of competition ranked just below the World Cup). There are also individual grants to athletes to help them attend World Cup events. Last year those winter projects support for event attendance was over $180,000.

NNF also sponsors domestic racing by being the title sponsor for the Supertour. The Supertour is the highest level of race competition in the United States and consists of a race series spread across the country. Success in the Supertour often leads to a spot on the U.S. national team or start rights in the Tour de Ski. Last year NNF subsidized the cost of the Supertour to the tune of $23,000, which covered almost 60 percent of the tour’s prize money.

One of the NNF’s other successful winter projects is its Trail to Gold program. The T2G is a coaching grant that supports developing women coaches and technicians in an historically male dominated profession. Bernie Nelson who was just hired by the U.S. team as a full time technician was a T2G funding recipient.

A critical piece of the puzzle for the NNF is coordinating between itself and the U.S. national team. That’s where Matt Whitcomb comes in. Whitcomb is the head coach of the U.S. ski team. He is also on the NNF Board of Directors. Whitcomb provides the Board with an invaluable overview of the needs of developing skiers, and what a successful development program looks like. “The NNF is the bridge between being a U14 athlete and being an Olympian,” said Whitcomb. “NNF picks up and assists with projects between those two things where athletes are most likely to quit because of funding challenges.”

“The NNF and national ski team are critical partners, but we’re really different puzzle pieces that just fit really well together where the NNF funds younger kids, and the U.S. ski team funds the older or more successful athletes. Our philosophy at the NNF is that all hard working athletes with big goals should be able to compete in the sport regardless of their economic status” The NNF states that there is funding which touches over 250 athletes per year, with funding from thousands of donors. “We have a three year fundraising average of raising over $500,000 a year, said Whitcomb.”

Often part of the NNF funding process is to generate individual amounts of support for certain events. For example, there might be a dollar amount set aside for the U23 championships which is then divided between different athletes. It can start out as a large pot of money, but by the time it’s divided between all the athletes and support crew, the dollar amount shrinks significantly. For example, it previously allocated over $84,000 in total to the last Junior World/U23 Championships. But after the math is done, it only comes out to several thousand dollars per athlete. It’s a big help but doesn’t cover an athlete’s entire cost. “There’s 10 wax techs alone that come to World Juniors, and around 24 athletes,” said Whitcomb.

Athlete buy-in is critical to NNF’s mission. Athletes are part of the fundraising efforts and build important ties to the cross-country community. Athletes are encouraged to actively participate in the fundraising process. “We don’t cover any project completely,” said Whitcomb. “The goal is to leave some of the responsibility up to the club and the athletes. If they all do a little bit (the athletes), it will really move the needle for an organization like this.” The NNF is proud of width and breadth of its donor base, with over 1,000 individual donations for its drive for 25 fundraising effort, it demonstrates its status as a grass roots organization. “Our window is at the grass roots level. There are people that donate five dollars recurring monthly. You know what it means to those people. We’re trying to sell shares of this great journey to as many donors as possible.” You may have heard of the Drive for 25, but not really known what it was about. It’s one of the NNF’s principle fundraising efforts. Last year it raised over $122,000.

It’s not just racers who benefit from the NNF’s support. High level racing needs high level officiating. At every FIS (International Ski Federation) event there are teams of technical delegates who are the equivalent of officials or umpires. Without the technical delegates, high level racing doesn’t happen. In the U.S., these positions are volunteers, but there are significant expenses attached to being a delegate. NNF has launched a new program to offer grants to individuals trying to gain technical delegate status to help offset part of the expense. It’s part of NNF’s efforts to maintain the flow of talent and treasure which feeds the cross-country pipeline.

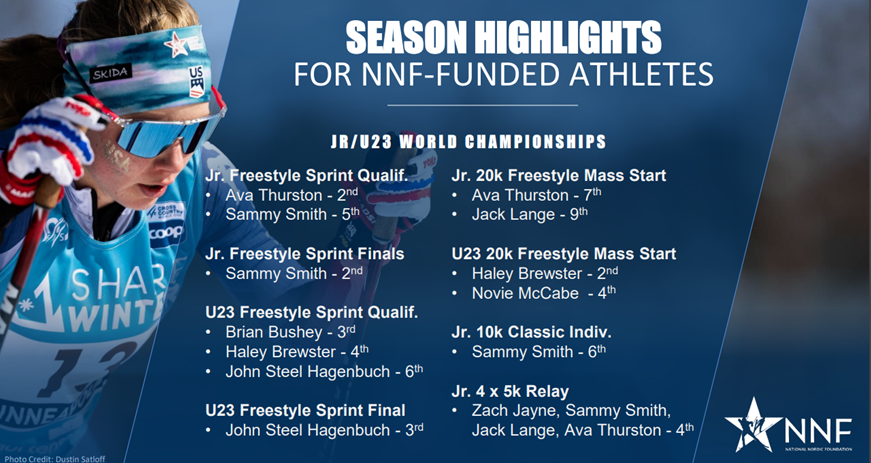

The NNF proudly points to athletes’ success as proof that its support continues to feed the American pipeline for world class ski talent. In the most recent Junior/U23 World Championships nine different NNF funded athletes finished in the top 10 in different events. In addition to the junior level racing, it also provided funding which contributed to 151 world cup starts. The results from that effort were over 20 top 30 World Cup finishes for NNF supported athlete. Another sign of NNF fulfilling its mission is that many previously NNF funded athletes have recently achieved United States A or B team status, including Sammy Smith, Kevin Bolger, and Will Koch.

Every time one of these developing athletes achieves success in competition it helps moves them along the pathway to becoming a member of the United States A or B team which is where the other side of the funding bridge is met and continues the pathway to Olympic success. “Take a look at the last Olympic team. Everyone of those athletes, earlier in their career, had received funding from NNF.”

It’s fair to say that without NNF support the pipeline of developing skiers would be limited to athletes from wealthy backgrounds or those who have the good fortune to have the marketing skills to promote themselves on GoFundMe pages or Instagram. As long as it continues to receive support from the Nordic community, NNF will continue to be the funding bridge for up and coming athletes.