ZHANGJIAKOU — Patrick Moore is a cheerful accountant from Edmonton, Alberta. Tim Baucom spends his summers working sales for a Vermont plank flooring company. Oleg Ragilo runs a cosmetic shop in Estonia with his wife.

Jessie Diggins, the American cross-country ski star, couldn’t have won her Olympic bronze without them.

Moore, Baucom and Ragilo all belong to America’s nine-member ski service team here — a mix of mostly paid staff and a couple of volunteers like Moore.

“I can’t speak highly enough of their work ethic — they’ve been out here every single day, hours and hours and hours, probably skiing like 50 k a day,” Diggins said after finishing eighth Thursday in her third race of the Games. She added, referring to her medal-winning ski: “They delivered such a clutch performance the other night.”

The service crew is charged with the complicated, high-stakes work of choosing the right skis and wax for the snow conditions in Zhangjiakou, the mountain resort town outside Beijing where Olympic cross-country events are taking place.

The task sometimes can make the difference between an average day and a medal.

But the work, which happens in drab tan buildings off a corner of the stadium, is relatively anonymous — except when things go wrong.

“I think it’s sometimes hard for people at my regular job what I look like here,” said Moore, the accountant. “And it’s probably hard for people at this job to understand what I look like there.”

The U.S. service team is composed of a mix of Americans and Europeans — including Ragilo, who previously waxed for superstars in Estonia and is something of a legend there.

To appreciate the crew’s work requires a quick lesson in ski technology.

Cross-country ski bases — the part that slides across the snow — are generally made of a plastic called polyethylene, or p-tex. The material has tiny pores, somewhat like a sponge, which means it absorbs wax that’s ironed or rubbed in by technicians; the excess can be scraped off to leave what appears to be a smooth plastic surface.

Manufacturers produce different waxes to help the skis slide faster in different conditions: warmer or colder, natural snow or man-made.

The waxes are typically layered, and they can be applied in different ways — ironed in, rubbed in with a cork or even a spinning wool cylinder attached to a drill, for example.

Technicians can also enhance the gliding potential of skis with metal tools that press tiny, intricate patterns into the bases, known as structure. Then there are the skis themselves, which are built stiffer or softer to suit snow conditions. American athletes each brought dozens of pairs to the Olympics — perhaps 300 total.

Sorting through each of those variables and identifying the best skis, waxes and structures takes hours and hours of testing. U.S. service team members arrived in Zhangjiakou a week before the first race, and got to work.

“None of us are scientists,” said Baucom. “But we just tinker around with all this stuff.”

The crew spends its first day or two skiing the race courses, setting up gear and getting a feel for the place. Then, they start testing the first layers of waxes and the best methods for applying them, as well as durability: How far can they ski before the wax starts losing potency?

Most of the testing is done by feel, with two technicians gliding down a hill, side by side, on two pairs of skis with different waxes to see which pair is faster. The American technicians can ski 30 kilometers a day or more; some or the Scandinavian teams with larger staffs have workers whose sole job is testing and can ski twice that far.

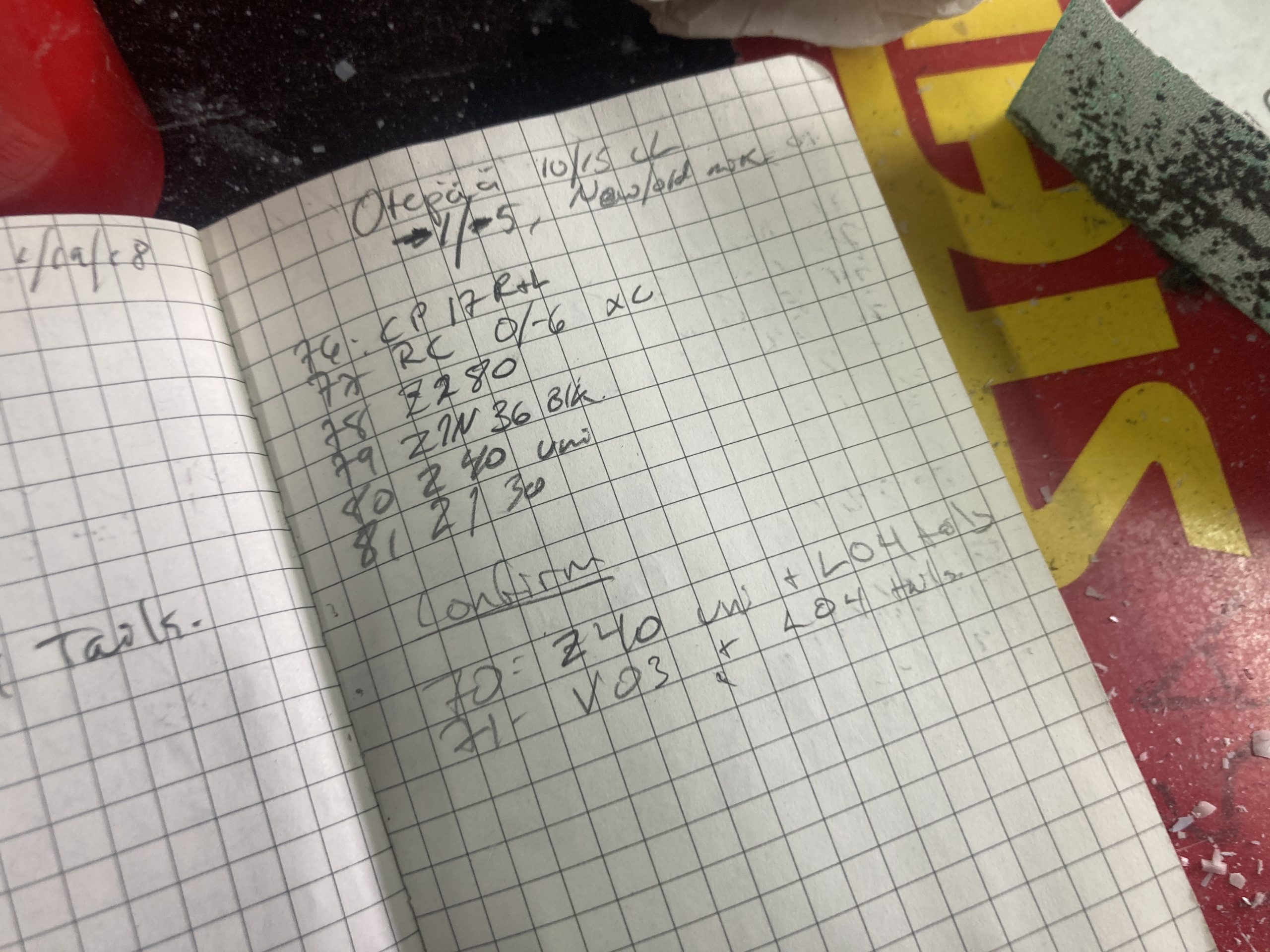

When race day arrives, the U.S. team may have tested 50 or 60 types of glide wax, and a similar number of kick waxes, which skiers use to grip the snow and push themselves uphill.

They’ll narrow that number to perhaps 16 waxes to test in the hours before the gun goes off. Athletes, who are paired with the technicians, will also test a handful of pairs of skis before a race to see which are fastest.

The Americans aren’t typically expecting to find a magic bullet that makes their skis the best in the field, said Baucom, the U.S. team’s head of glide waxing in Zhangjiakou.

“You always want to have skis that are ridiculous, and make you look good,” he said. “But really, our goal is to have competitive skis. And it seems like in these conditions, as far as I can tell, almost every team has had pretty competitive skis.”

The conditions in Zhangjiakou were the subject of intense speculation before the Games.

The area is not far from the Gobi desert and gets minimal precipitation, so skiers are racing mostly on manmade snow. Before the Games, Baucom heard about storms that deposited sand on the trails that ruined skis.

But so far, he said, the skiing at the Olympics has been quite good, even if the snow is a little dirty and wears away wax a bit more quickly than usual.

“It’s not throwing us for a loop as far as being very different from other really cold, dry snow that we’ve raced on,” Baucom said. “It’s abrasive, but it’s not, like, crazy.”

Ski preparation at the elite level can be something of an arms race: On the European World Cup cup circuit, bigger teams, including the U.S., travel with huge trucks that have been outfitted as roving wax rooms at a cost of $500,000 or more. Those trucks, however, did not make the trip to Zhangjiakou.

Scandinavian teams spend more money on ski service and have bigger workforces, which can sometimes produce inequities. At the World Championships in Germany last year, the U.S. technicians had an especially tough day in the women’s pursuit race, where the skis they gave athletes were too slow to be competitive. Baucom described the feeling as “gut-wrenching” for the staff.

When things go wrong, the U.S. team will often collect skis after the race and retest, to see what went wrong.

At the Olympics, though, conditions have been stable and relatively straightforward for waxing, even after a flurry of fresh snow Saturday morning. So far, the American athletes have had few complaints.

“It feels good to know that everyone has a pretty fair shot,” Diggins said. “I’m just so grateful to our staff, because we win as a team.”

Nathaniel Herz

Nat Herz is an Alaska-based journalist who moonlights for FasterSkier as an occasional reporter and podcast host. He was FasterSkier's full-time reporter in 2010 and 2011.