The Craftsbury Outdoor Center (COC) in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont has emerged as a premier year-round cross country ski training venue. The COC has also been a leader in embracing and promoting sustainability and environmental stewardships through their own day to day operations and educating their customers. They have invested in energy efficient buildings, a wood-burning central heating system, solar energy, and an abundant garden which allows them to grow much of their produce on site.

Following this ethos, the COC has partnered with the University of Vermont (UVM) on a project to develop an innovative over summer snow storage system. The system aims to guarantee one to three kilometers of skiable snow by Thanksgiving each year.

“Storing snow over the summer enables us to make the snow at the coldest times in winter, when the snowmaking is most efficient, rather than in November when the temps may be marginal,” wrote COC owner Judy Geer. “[It also] assures skiers will be able to will be able to stay home in Vermont or New England over Thanksgiving and be able to get in good training, rather than spending money and increasing their carbon footprint on trips out west.”

Snow storage systems are used in several locations throughout Europe and were responsible for making the cross-country venue at the 2018 Olympics in PyeongChang viable. So why does this development at the COC require a team of university scientists?

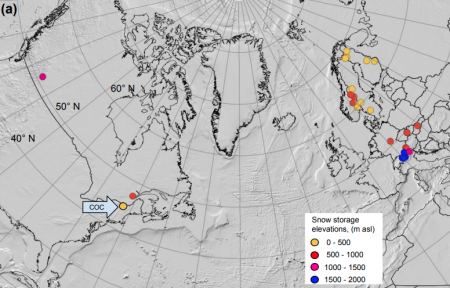

Paul Bierman, professor of Geology and Natural Resources at UVM, project leader, and nordic ski enthusiast, explains that the project is unique because Craftsbury is the lowest in latitude and elevation of any snow storage site. The majority of cross-country venues with snow storage systems are located in high latitude Scandinavia or in mountainous high altitude areas in Central Europe. Craftsbury Common, on the other hand, sits at about 44.6 degrees north latitude and about 353 meters in elevation.

“No one has ever tried [snow storage] in the worst of all possible combinations: low altitude, humid, low latitude. This was really an interesting merge between university science and engineering, and a center that is committed to trying new things as well as sustainability. Maybe that’s why it worked,” Bierman said with a laugh.

Bierman explained that the impetus for the project was born a few years ago around Thanksgiving when temperatures in Vermont were too high for snowmaking and no natural snow had fallen. A dismal combination for a skier. he COC could only produce a 100 meter lollipop on their soccer fields. While out on a ski, Geer and her husband and co-owner Dick Dressigacker began chatting with Bierman about the concept, knowing his interest in snowmelt and snowmelt hydrology.

Bierman spearheaded the project with a scientific lens. He recruited his undergraduate assistant Hannah Weiss who has continued with the project as a graduate student, and a colleague in mechanical engineering began with a feasibility study. They found inspiration from old fashioned Vermont ice houses, which predated modern refrigeration. Ice house technology consisted of ice harvested from the surface of rivers and lakes during the winter. It was then covered with straw and sawdust and preserved in a partially underground building to keep perishable food cool in the summer.

The team identified a storage site in a pond that no longer held water and instrumented the ground at varying depths to measure temperature.

“We wanted to make sure that the ground was not so warm that we were just going to melt the stored snow from below.”

The team monitored the temperature variation over the course of a year.

“What we realized is because of how far north Craftsbury is, ground temperatures weren’t doing all that much and there really wasn’t going to be that much flux of heat from the ground into the snow pile. So that got us thinking, ‘Okay, maybe this is going to work.’”

Next, with the help of the Craftsbury grooming team, they created two test piles at the end of the 2018 season in order to determine an optimal system for insulating snow through the summer. They covered the piles with roughly 25 cm of wood chips which were instrumented with thermometers. They tested a variety of covers including foams of different densities, concrete curing blankets, space blankets, and reflective mylar over the top to deflect solar radiation.

After monitoring the piles through the summer, they identified the optimal setup. On top of the manicured snow pile, a concrete curing blanket was laid primarily to protect the snow from debris. The blanket also adds some insulation. Next, a layer of wet wood chips 20 to 30 cm deep was spread, providing the majority of the pile’s insulation. Finally, a white mylar space was stretched across to reflect thermal energy from the sunlight. This system proved highly effective.

“When you monitor the temperature underneath that concrete curing blanket, it basically doesn’t change. No matter how hot it is outside, it basically stays at zero.”

With a scientifically-backed storage plan, the UVM and Craftsbury collaborators went into the 2019 season ready to give snow-storage a go. The pond site was improved and a road was built to improve access.

Keeping in line with its mission of sustainability, the COC purchased new energy-efficient airless snow guns which use between a quarter and a third of the power than older model fan guns. These new guns ran for a week in February, blowing roughly half the COC’s annual water allotment into a large pile.

“The beauty of it is that they don’t have to power fans anymore, so it was a lot less energy,” explained Bierman. “And they did it in the middle of their high season, and because they generate their own electricity for these guns, they have a heat recapture unit on the generator, so a significant part of the energy that would have gone up the chimney as waste heat, was now heating dorms that were full of people.”

He added that were the snow blown in November, as is the case in most snowmaking operations, the COC would have been mostly empty, meaning the heat would have been wasted that way as well.

Groomers ran a pistenbully back and forth over the pile to pack it more densely: dense snow melts more slowly. The pile was shaped with an excavator, then the team waited as it transformed into corn snow in the spring. Then the pile was covered with wood chips and the white reflective covering.

Though the storage method was tested the year before, the scale of the pile had increased dramatically.

“This was a big logistics year,” Bierman explained. “How do you do this? How do you shape a pile? How do you put chips on it? How do you put a cover on it? How do you keep the cover from blowing away in a big spring wind storm? Which it did the first time,” he laughed.

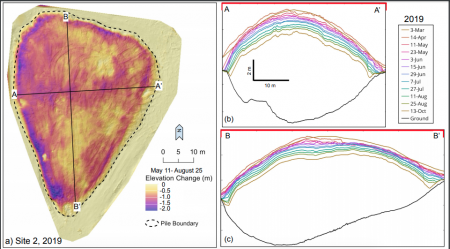

Once the pile was tucked neatly under its multilayer covering, the team sat back and monitored it regularly throughout the summer using a new style of survey equipment called terrestrial “LIDAR”, which stands for light detection and ranging. This allowed the team to track changes in the 3D surface of the pile, thereby measuring the change in volume.

“It became pretty clear by mid-July that this pile wasn’t shrinking very quickly. By the last scan in October, we had about 65% left by volume of what we put in there. And that is pretty much what Europeans in the Alps get.”

He explained that the limited existing data suggests that the average retention by volume of other snow storage sites is between 60-70% on average.

By their measurements in early November, the pile contained 5-6000 cubic meters of usable snow, which translates to 2-3 km of coverage at 50 cm deep and a few meters wide.

“In any normal November, that would be a godsend. Most of the early November skiing at Craftsbury is a big lollipop in the upper soccer field and down the hill in the lower soccer field, where people are going in one direction on maybe a 200 meter course around and around and around.”

He added that the preserved snow would allow “more interesting” terrain to be opened early, such as “Lemon’s Haunt”, a 1.6-kilometer blue square trail which rolls through the woods.

Feeling confident that the COC could provide a few k of skiing by its projected opening day on November 16th, the team began scraping off the layers of wood chips in early November. Then, in an unforeseen plot twist, the first snowfall of the year arrived, coating Craftsbury with a thick layer of natural snow. This interrupted the original plans of spreading the pile, but allowed the COC to open 25 kilometers of trail on opening day.

“The pity is that it didn’t work out as everybody anticipated, which was to lay a couple k of base down with this icy stuff, then have the natural snow sit on top of it, which would preserve the natural beautifully.”

He laughed that no one would want klister snow laid on top of their blue wax conditions.

So how would the pile have been transformed into ski trails had Mother Nature not trumped the scientist’s plans?

Bierman explained that during the summer, the snow transforms into “firn”, a term used most commonly with glaciers to describe an intermediate stage between snow and ice. Though icy and dense, the substance maintains its granular quality.

He explained that without the world-class groomers and equipment at the COC, making this into skiable terrain would not be possible.

“The beauty of Craftsbury is how well they groom. Their grooming is spectacular, they’ve got three piston bullies, they’ve got this.”

Prior to the natural snowfall, the grooming team had been meticulously cleaning an excavator and dump truck to ensure that dirt was not introduced into the clean snow pile, as the sun on the dark-colored dirt increases melting. Dirt in the base would be further mixed into clean natural snowfall, creating a problem from the get-go. Not to mention skiing in dirty snow is not recommended for your bases.

With clean equipment, the team would begin trucking snow to the furthest point, working their way backward toward the pile. Once the snow is laid out, groomers can work their pisten bully magic to create a surface that is pleasurable to ski.

The COC is developing a plan for how the stored snow will be used, which will be dependent on weather and natural snowfall. Some stored snow may be kept in order to patch holes in the event of a warm spell.

Next year, the team intends to again create as large a pile as possible and continue to fine tune the storage methods.

“This is just the first year, so we have a lot to learn–both in terms of process, and also environmental and cost-effectiveness,” wrote Geer.

Bierman explained that the logistics of properly covering the large pile requires practice, but a lot of pitfalls have been flushed out in the first two rounds of the experiment. The COC staff will be refining their method of covering the surface with an adequate layer of wood chips which does not crack or slump, and overlapping layers of the white reflective cover to reduce the chance of exposure and rapid melting.

“Nature is going to help us because now the ground underneath that pile is cold. It has had cold melting snow on it all summer, so presumably the ground underneath there is 0 degrees C and saturated with 0 degrees C water, and it’s only going to get colder this winter.”

Bierman continued that other snow storage facilities have experienced improvement in retention each year over the first few years.

Depending on what winter has in store, the COC may increase the volume of snow that is blown into the pile in 2020.

“If we have a good snow year and they still have water left in February, they’re just going to blow it into the pile,” said Bierman.

He continued that they could scale up by an additional 50% over last year’s volume.

Overall, the project has been a great opportunity for the COC to improve upon existing snowmaking methods and to guarantee snow for Green Racing Project athletes, the local junior teams, and recreational skiers alike.

“It gives the place an insurance policy. It doesn’t matter when you put that snow away, by putting it away, Craftsbury can reliably say that they can open in November. We don’t even have to wait for snowmaking weather.”

What would it take for over summer snow storage to be implemented by other ski areas? Bierman explained that the recipe is outlined in great detail on the project website and also in a technical paper written by the UVM science team, which is currently under review (full citation below).

Clearly, the project requires significant resources: a place to store snow, an excavator, snowmaking equipment, pistenbully, coverage supplies, not to mention man-power. It is not, perhaps, readily accessible to small family run ski areas, but Bierman expressed that many major cross country centers could consider it.

Apart from the superficial benefits of early season skiing, Bierman imparted the importance of the underlying reason for the project.

“We’re on a trajectory of global warming unlike anything we’ve ever seen, and this is a Band-Aid. It’s a Band-Aid that might hold us for 10, 20, 30 years, but it’s not getting at the root issue here which is decarbonizing the global energy system. Unless we do that, all winter sports in these mid-latitudes are going to be extinct. We can’t save enough snow to have a nordic season if it doesn’t get cold anymore. If you look at the Vermont climate assessment, if we don’t change how we’re doing business — sort of the business as usual scenario, how we operate — we’re going to look something like the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee by 2090.

“So this is a fun thing, extend the season, that’s all great, but we have to take some serious action as a global community to deal with climate change and the use of carbon fuels.”

Overall, both Bierman’s team and the folks at the COC are pleased with the results produced by the project and the many benefits it has provided in its nascence. The large pile of preserved snow stands as a testament to creativity, dedication to sustainability, and the power of problem-solving.

“The takeaway is that it works,” concluded Bierman. “And actually, it’s a lot of fun and it’s been a great way to share what we know about climate change, and not only about climate change adaptation, which is what you’d call this project, but also climate change mitigation which is ‘how do we get on the front of this?’

“It’s a great educational tool about ‘climate change matters, and let’s see what we can do about it.’ We’re being forced to do things in New England that 20 years ago you wouldn’t have thought about doing.”

To bring this article to life, check out this video created by Bierman’s daughter, Quincy, who is a member of the junior program at Craftsbury.

References: Weiss, H. S., Bierman, P. R., Dubief, Y., and Hamshaw, S.: Optimization of over-summer snow storage at mid-latitude and low elevation, The Cryosphere Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-2019-56, in review, 2019.

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646