This piece was originally was published on statisticalskier.com and is republished with permission.

The recent episode of the Devon Kershaw Show by FasterSkier (which I’ve been enjoying quite a lot) included some discussion of the noticeably large time gaps in the men’s classic sprint World Cup in Oberstdorf, Germany. Beginning at around 25:18 they discussed a variety of aspects of the large time gaps. I thought that some of the things they noted would benefit from some cursory looks at some data. In no particular order

“We’ve seen this before from Klaebo”

Indeed we have. Over the past decade or so when Klaebo has won a sprint qualification the margin has averaged around 1.65% in classic and 1.12% in freestyle. His margin in Oberstdorf was 1.31%. So this was not even particularly extreme for him, in terms of a gap over second place.

30th place is 15 second back

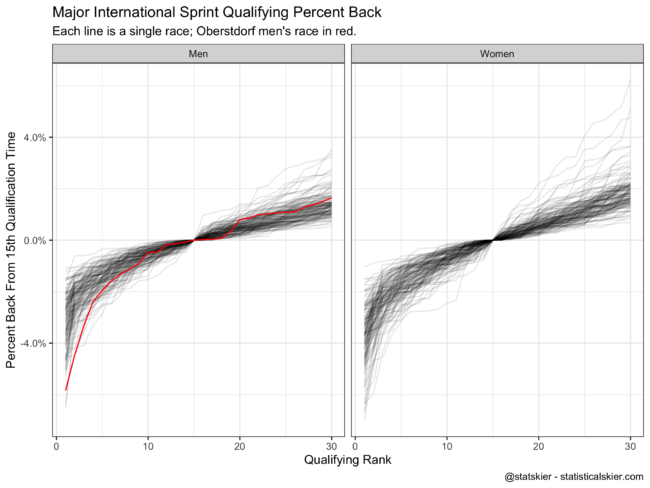

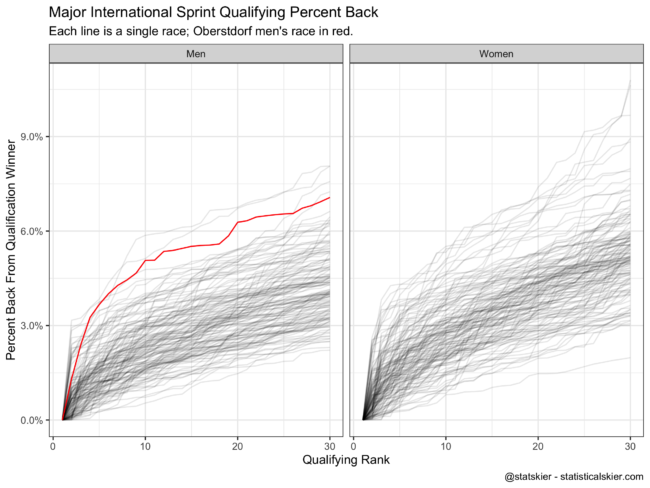

That is a remarkable time gap for a World Cup sprint qualification, for sure. But how unusual is it for much of the top 30 field to be that far off the pace? Let’s take all major international (WC, OWG, WSC, and TdS) sprint races over the past 10 seasons and plot the top 30 qualifying %-back values for each race as a line.

That’s definitely unusual. One of the things that’s interesting about gauging performance in individual sports like xc skiing is that there’s a subtle distinction between a particular outcome arising from one person skiing really slowly and another person skiing really fast. And of course it could be a combination of the two.

That’s definitely unusual. One of the things that’s interesting about gauging performance in individual sports like xc skiing is that there’s a subtle distinction between a particular outcome arising from one person skiing really slowly and another person skiing really fast. And of course it could be a combination of the two.

Devon and Jason discussed the fact that if you’re 30th and 15 seconds back in qualification, it seems really unlikely that you have a realistic shot at winning. But I think that underplays somewhat how unlikely it is for anyone to win a WC sprint race when you qualify that slowly, regardless of the time gap.

Over ten seasons, men qualifying in 25th-30th have reached the podium only 16 times, or around 1.92% of the time. On the women’s side, it has happened only 7 times or 0.8% of the time. Actually winning is obviously even rarer: 5 times for the men and only once for the women, for 0.6% and 0.1% respectively. So the folks qualifying in the back of the field are very unlikely to win, even with “normal” time gaps.

Of course, it is easy to get confused about the causal relationship here. Fast qualifying times will tend to be correlated with all sorts of other fitness characteristics that lead to good performance in the heats. It’s not the fast qualifying time itself that leads to better performances.

Let’s return, though, to the unusual time gaps themselves. Certainly, some specific talented sprinters had rough days (Ustiogov and Iversen were mentioned in the podcast). But if you’re sitting in 30th, 15 seconds out in this particular case, should you be saying to yourself, “Geez, I skied pretty badly!” or should you be saying, “Geez, the top 3-4 guys really just had another gear today!”. (Or obviously somewhere in between.)

This is one of the problems with measuring performance based on only the winner. Devon talked (correctly, I think) in the podcast about how if you’re 15 seconds back from the winner in qualification that’s a pretty good signal that you’re not going to win. But, it is a potentially quite misleading signal about how you skied relative to your own performance history!

One approach I happen to like to use as an additional perspective is to calculate percent back values based on the median, or middle, skier. What do the percent back curves I plotted above look like if I recalculate them based on the skier who qualified 15th?

Now which part of the red curve looks more unusual? This look at the race would at least suggest that the top 4-5 men were the ones who had unusual races, rather than the the field as a whole. The back of the qualifying field seems a bit more behind 15th place than usual, but not nearly as dramatically.

Obviously, this doesn’t change the calculus for how close you are to winning. If you’re racing against people like Klaebo who can put down winning margins like this, it is small comfort to be told that you didn’t really ski any slower than you usually might. But it is useful to keep in mind when you see time gaps like this that it is quite possible that the folks in 25th skied just as fast as they did yesterday, a month ago, a year ago (maybe faster!). In other words, it can be a signal of how much work you have to go, but not necessarily that the work you’ve done so far isn’t helping or even making you slower.

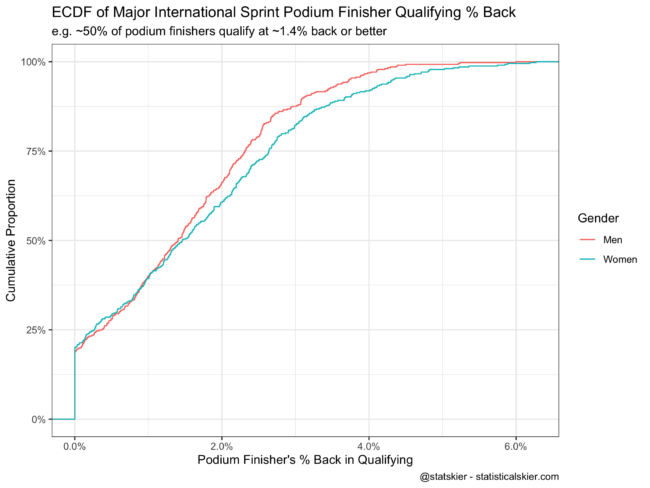

How fast do podium finishers qualify?

I’m glad you asked! Let’s look at that with the following plot:

ECDF stands for “empirical cumulative distribution function” which is quite a mouthful and isn’t a graph that normal folks interact with regularly, but don’t panic.

This just graphs the cumulative proportion of podium finishers (y-axis) who qualify with a given percent back or better (x-axis). So if you pick a spot on the y-axis, say 25%, and move horizontally until you hit the curve you look down on the y-axis and see that ~25% of podium finishers qualified with a percent back of ~0.4% or better. Don’t forget the “or better”.

Similarly, ~50% of sprint podium finishers qualify at ~1.4% back or better. And so on. The vertical line each curve starts with represents the fact that ~20% of podium finishers actually win qualification (0% back).

Looking at this it seems that 1.5-2% back might be a good target to think about if you want to be landing on the podium in World Cup sprint races. If you can’t qualify at least that close, you’re probably not setting yourself up for a good shot at a podium.