Twenty years ago today, on Nov. 2, 1996, a ski race sanctioned by the International Ski Federation (FIS) was held in Fairbanks, Alaska, on the trails at Birch Hill. It appears to be the earliest FIS race ever held on natural snow in the Northern Hemisphere. This is a look back at that race, and at the significance it has, or does not have, for some of its participants.

Setting the stage

It was the final days before a hard-fought presidential election. Clinton was widely expected to prevail over the Republican candidate, although a strong third-party showing and voter dissatisfaction with the two major parties were complicating the electoral calculus. The Alaska Republican Party was running newspaper ads promising to “defend State’s rights.” And people were skiing in Fairbanks. Plus ça change.

There were also some differences. The front page of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on Nov. 3 ran an article headlined “Dole hoping for an upset” over, of course, Bill Clinton. Then on Nov. 4: “Perot plans last-minute television blitz.”

Elsewhere in the paper, movie listings included the Leonardo DiCaprio vehicle Romeo + Juliet. Agate type in the sports section recounted promising rookie Ray Allen leading the Milwaukee Bucks to a victory over the Boston Celtics. (It was the second game of Allen’s career. He would go on to play 1,298 more games after that.) And an ad for an ISP, or internet service provider, explained to potential customers the appeal of “the Internet.” You could “interact with people from around the world,” it promised, or, “Find answers and advice in newsgroups.”

In Fairbanks, meanwhile, it was winter, and it had been winter for a long time. The News-Miner reported that October had seen record-breaking cold, even for Fairbanks, with an average temperature for the month of 13.6 degrees. Through Nov. 3, it had snowed 22 inches so far that winter; given those temperatures, and the relative lack of solar radiation in Fairbanks in winter, most of it was presumably still on the ground.

The Nanook Challenge

Given this weather and snow conditions, it hardly seems newsworthy that a ski race was held. Plus several members of the U.S. Ski Team (USST) had been in town for early-season training, so the skiers were there.

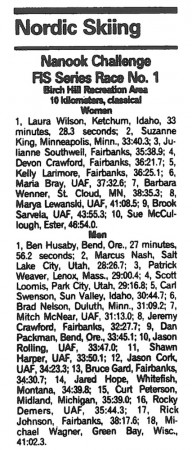

The field for the 10-kilometer classic interval start – official title the “Nanook Challenge: FIS Series Race No. 1” – was small but distinguished. There were 10 women and 18 men entered. At least four current members of the U.S. Ski Team competed, along with several former USST members.

The top-five finishers in the men’s race were Ben Husaby, Marcus Nash, Patrick Weaver, Scott Loomis, and Carl Swenson, respectively, a bevy of elite skiers that would not have been out of place at a mid-1990s national championship race. (Indeed, all five men would place in the top seven in the 15 k skate race at U.S. nationals later that winter in Bend.)

The women’s podium was headed up by USST skiers Laura Wilson and Suzanne King. Third place went to Julie Southwell, described by the News-Miner as “a national team contender who trains in Fairbanks.” (Five years later, a profile of Southwell by Inge Scheve in The Bulletin of Bend, Ore., would call her “a former Colorado resident who says she sort of follows the snow.”)

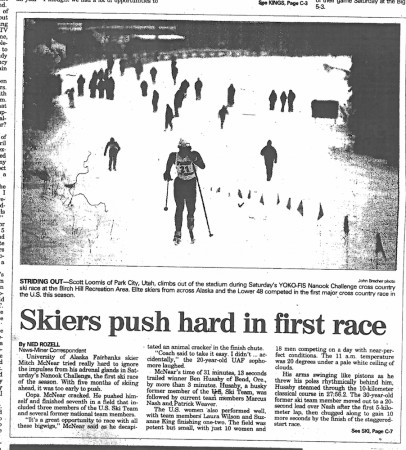

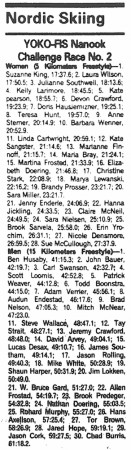

Wilson’s winning time was 33:28 for 10 k. Husaby finished the same course in 27:56. Conditions were described in the News-Miner as “near-perfect,” with an 11 a.m. race temperature of “20 degrees under a pale white ceiling of clouds.” (The season’s second FIS race, a 15 k skate, was held the following weekend, in arguably less perfect conditions. The high temperature for Fairbanks on November 9, 1996, was –1°. The low was –26°.)

(Story continues below)

Looking back

Swenson, the fifth-place finisher in the opening 10 k classic, has fond memories of Fairbanks as an early-season training destination generally, though scant recollections of this race specifically. When asked about this race in a recent phone interview, following his workday doing indigent defense for the New Hampshire Public Defender, Swenson began by musing, “I’m just trying to place what year that would have been,” and attempting to reconstruct whether World Champs had been held that spring or the year before. “We’d always have a race real quick after we got there,” Swenson continued. “And we’d get to Fairbanks in mid-October.”

“I remember it fondly,” Swenson, now 46, says of Octobers and Novembers spent in the Golden Heart City. “Not a lot of sunlight, lots of skiing.” He adds that “everyone was so excited be on snow again; I always looked forward to it. I don’t know if everyone looked forward to it, but I always did.”

“We were always able to ski” somewhere in or near Fairbanks, Swenson notes, “but sometimes it was really thin. … There could be pretty bad skiing, but I always remember we skied.” They would – much like modern-day juniors competing in the Besh Cup series – stay at the Wedgewood Resort, and “we’d all pile up and drive to Birch Hill. When it was a bad snow year, we’d all drive up to an elementary school” that had trails (Salcha Elementary), “and it would be ridiculously cold.”

Swenson’s lack of specific memories may be attributable not only to the passage of time and multiple fall trips to Fairbanks, but also to the fact that Nov. 2 was early in the season for him in more ways than one. “I probably hadn’t done much rollerskiing” at that point, Swenson candidly admits. “I was still catching up.”

(Uniquely among top-level cross-country skiers, Swenson had “made the bold decision to pursue a professional mountain-bike career and continue to ski race internationally in the winter,” FasterSkier previously wrote. 1996 was his first summer of pro mountain biking in the “offseason.”)

When asked whether he had simply kept the rollerskis in storage through September or had at least gotten out a few times a week during the summer, Swenson at first suggests digging up an old training log from storage, then says, “it would depend on if I went to late-season mountain bike races that year. Sometimes I would be – World Championships are at the end of the season in mountain biking. In ’96, I think I would have been in Boulder. And maybe I would have started doing some rollerskiing in the summer – not much, if any.”

Swenson was clearly unconcerned about his results in a November race two months before U.S. nationals and more than three months before World Championships. He recalled that his focus for his first two weeks back on snow would have been volume, and guessed that he would have logged approximately 20 hours of skiing per week while in Fairbanks. “I’m sure everybody up there was concentrating on volume, and things like that,” Swenson notes. “There would be people chasing points, to make an early trip – but I doubt anyone was doing that up there.”

Swenson improved his position with a third-place finish in the 15 k skate a week later, suggesting that he may have been racing his way into skiing shape.

At the top of the results sheet, Husaby won both races, the 10 k classic on Nov. 2 and the 15 k skate on Nov. 9. His memory of that fateful week in Fairbanks borders on the eidetic. “That weekend actually stands out for me as one of the more memorable ones in my ski career,” Husaby recently said when cold-called about a race from the Clinton administration.

Husaby, who turns 51 next month, spoke with FasterSkier by phone from Bend, where he works as executive director of the Bend Endurance Academy. (Husaby once cracked that he enjoys being a ski coach because “I get to drive a Ford Econoline van down winding roads in inclement weather.”) Husaby clarified that in his current job he coaches only one skier, national-class athlete Dakota Blackhorse-von Jess; he assists nordic director Bernie Nelson and will go out with other athletes, but says that he is following Nelson’s lead.

Husaby still recalls how fast he skied, but poignantly acknowledges that his timing was somewhat suboptimal.

“I’ll just say, it was the fastest I’ve ever skated, for sure,” Husaby declares. “And you certainly don’t want that to happen in the first week of November, but it did. It’s bittersweet, because it’s the wrong time, but it was amazing. Those two races, they were effortless.”

Husaby speaks with evident emotion about the sensation of skiing so easily:

“So, nobody wants to be a Christmas star, and I was a November star. But, the race course [in Fairbanks] was a very challenging race course, and I blew around that course effortlessly. And that was a really, really cool feeling. I had traditionally struggled in tough skating race courses, and, you know, I walked all over everybody. And so, you know, that was exciting. And one of the things I remember is, how cold I felt being as quote-unquote ‘skinny’ as I was. I was in the low 180s. And I was colder than I had normally been.

“I also remember feeling really light and fleet and dynamic. I remember – and it’s always weird, because when we got back to the hotel – you know, those first races of the year, people are always talking about how they’re going to get better, where they made mistakes… generally everyone wants to downplay their early races. And here I was – I’m looking in retrospect in terms of how fast I really did ski. At the moment I didn’t realize that that was probably as fast as I had ever gone, but in retrospect, I realize, wow.

“There were a couple of World Championship results, there were a couple World Cup results where I was competitive, and probably moving along at the same speed – but this particular weekend, it was completely effortless.”

Husaby had been a member of the U.S. Ski Team from 1991 through 1995, but in fall 1996 was training solo. But he finished ahead of all current USST members in both races in Fairbanks.

“Particularly the skate race,” Husaby enthuses, “I mean, for me to beat everybody by over a minute – I think it was a minute and change – in a 15 k skate. I mean, I never did that. I’m not really sure why.” (Husaby correctly recalls that he beat second-place John Bauer by 1:04 in the skate race.)

At the time, Husaby felt strongly that his performance merited selection for bigger stages: “I do remember being like, ‘God, I wish they would have selected me to go back to the World Cup.’ Because they sent Marcus [Nash]. They took Marcus, not me. And I do remember being like, ‘Dangit, I killed everybody, they should be taking me.’ But it’s always like that – you always think that you should be the one that’s named.”

But he now waxes much more philosophical about the vagaries of team selection. “I’ve had 20 years to think about it,” Husaby now analyzes, no regret or animosity in his voice. “There are a lot of arguments why I should have been chosen for it, and a lot of arguments why I shouldn’t have been chosen for it. It’s just the nature of sport.”

As he left Fairbanks in November 1996, Husaby had high hopes that these results presaged a breakthrough season for him.

“Like any athlete, you think, ‘Oh my gosh, this is the start – it’s really going to happen here.’ Particularly when you’ve had five years of mediocre racing on the World Cup, right? … In the previous five years, I had everything [in World Cup results] from low 20s to, you know, 112th place. And so all of a sudden a result like this comes along early in the season, and I’m thinking to myself, ‘Man, if this is the start of things to come, this year is going to be totally lights out.’ ”

Husaby did not receive World Cup start rights that season, and in fact never raced on the World Cup again. He spent the 1996/1997 season on the domestic Yoko Cup, an inchoate version of the national-level race series that ultimately became the SuperTour.

Despite – or maybe because of – the fact that the Fairbanks races ultimately proved to be a highwater mark of the season rather than a springboard to successful European racing, Husaby frequently uses the experience as a teaching moment for his athletes.

“As much as we really think that we have our finger on the pulse,” Husaby theorizes, “and that we can really dial in when we’re going to be fast, and really pick and choose the big events, and how it’s all going to play out – you never really know when you’re going to have your moment. You don’t know. The body and the mind are really – sometimes they’re diametrically opposed, sometimes they’re incredibly in sync, sometimes one is lined up and the other one’s not. And a huge part about athletic growth is just realizing that you never really know when you’re going to have your moment. So when you do have your moment, hopefully you get something from it, you gain something from it. For me, this was an indicator that my training, the change in training, had an effect, the weight loss had an effect, maybe the release of not being on the ski team any more had an effect.”

“I guess the moral is to pull something positive out of a good race, regardless of when it happens.”

When asked about his strongest memories from his time in Fairbanks, Husaby mentions two things. First, despite the subzero temperatures for the skate race, “I remember that that climb – I felt like Superman going up that far outer climb [on the race course]… I remember charging up it. It’s got like three rises in it.”

And second, “I remember that being a very cold week. … I wasn’t a ‘do a loop many times’ kind of guy. I was always an explorer. Well, I spent most of my training time in Fairbanks actually out on the White Bear [Trail] and out on the military roads. I used to bring really crappy skis, just so I could ski on the military roads. But I recall that week being incredibly cold. And my motivation was to ski out to the end of White Bear, look at the thermometer, and then ski back in. Just to reaffirm how cold it really was. That was it. Besides that race, that was my memory of that week.”

In addition to multi-time Olympians, other notable names on the results sheet include “Jason Cork, UAF, 34:23.3,” in 12th, surrounded by several of his teammates from the University of Alaska Fairbanks ski team. Cork was born and raised in Alaska, and graduated from North Pole High School in 1995. He skied for UAF before embarking on a coaching career that ultimately brought him to his current position as Assistant Men’s Coach for the U.S. Ski Team.

Early-season history

The participants may not have realized it at the time, but they were, in the world of high-level ski racing, making history. The race remains the earliest FIS-sanctioned race ever held on natural snow in the Northern Hemisphere, according to the FIS database.

(A FIS-sanctioned race is one whose results can be used to help calculate a skier’s FIS points, “theoretically a universal ranking system for skiers around the world who have never competed against one another.” Generally speaking, a FIS race is held on a course with climbs of specific height differential and grade, as well as a total climb requirement. A FIS race is held on a relatively challenging course, and attracts a relatively high caliber of skiers.)

Here are the earliest FIS races from 1996 to present, as listed in the online FIS results database. Amidst a host of early-November dates from several venues across northern Scandinavia, November 2, in Fairbanks, Alaska, stands out as the earliest by a small margin. But Fairbanks shares one significant thing in common with the other names frequently occurring on this list: a far northern latitude. Fairbanks is at, in round numbers, 65 degrees north latitude; Olos and Muonio, 68°; Inari, 69°; Beitostølen, a downright tropical 61°. (The Arctic Circle is at 66°34′.)

As FasterSkier wrote over a decade ago, Fairbanks in early winter presents a “surreal setting. … The air is still, day after day, and the temperatures hover around zero even though it is barely November.”

(The table distinguishes between natural snow races and artificial snow loops when relevant – it is truly impressive that Mora had a sprint race on a stored ribbon of snow on October 21, but it makes for an apples-to-oranges comparison to Fairbanks or Muonio. Also note that the 1996 cutoff for this table is not artificially hiding an earlier race out there. The earliest FIS race from any of 1990-1995 was held on November 6, 1993 (also in Fairbanks, also the Nanook Challenge). And by the 1990/1991 season, there are only a dozen races listed for the entire season (down from hundreds for 2015/2016), underscoring the limitations of the otherwise remarkable FIS database.)

All that said, simply skiing in Fairbanks in November is a news story on the level of “dog bites man.” September snowfall in Fairbanks is not unusual. Groomed (or at least dragged) skiing in October is expected. Throughout the 1990s, Birch Hill was a mecca for early-season training for high-level skiers from across the country. (The second FIS race of 1996, the 15 k skate a week later, boasted a top-8 of Husaby, John Bauer, Swenson, Loomis, Weaver, Todd Boonstra, Adam Verrier, and Audun Endestad. That’s a lot of good skiers. And a combined 15 Winter Olympics.)

Ken Leary is a longtime Fairbanks local who oversaw the low-key Wednesday Night Race Series ($20 for eight races!) for many years. In an email to FasterSkier, Leary wrote that “the first Nordic ski race of the season in Fairbanks is the annual Wednesday Night Halloween race held on the Wednesday nearest to Halloween.”

Leary added, “To my knowledge, Fairbanks has never had a Nordic ski race in the month of September, but it would have been possible in years 1992, 1993, 1996, and 2015 because of early snowfall.”

(In Anchorage, which like Beitostølen is situated at a balmy 61° north latitude, early high-level ski races on record include “a 15 km APU race that [then Alaska Pacific University head coach] Jim Galanes held on the Spencer Loop on October 25, 2001,” as recounted on local skier Tim Kelley’s blog. More recently, the University of Alaska Anchorage ski team held a time trial on the Spencer Loop a week ago today.)

And at the other end of the season, following a winter of roughly average snowfall but then a spring of record-breaking cold, Leary once hosted a race at Birch Hill on May 8, 2013, when the 6:45 p.m. start time occurred a full four hours before sunset. (The YouTube video is worth a quick watch (and not only because a cross-country ski race leads the sports news on local CBS affiliate K13XD Channel 13). It shows racers in shorts on what can only be described as close to 100 percent snow coverage on a 50-degree day. Many skiers have raced in midwinter in far worse.)

What it all means

There is an undeniable draw to being on snow – especially when you’re not supposed to be. (Or maybe especially when others are not, and you can brag on social media that you are.) Rollerskiing is good as far as it goes, but Annie Pokorny once credibly likened it to a rebound girlfriend, writing, “Every spring, Nordic skiers must undergo a reluctant breakup with the perfect girl” and console themselves with mere rollerskiing.

And so Pokorny and her Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation Gold Team teammates spend August in Australia, while the USST returns to New Zealand and the Snow Farm. Noah Hoffman goes to Passo dello Stelvio. Craftsbury Green Racing Project goes to Austria’s Dachstein Glacier, but precedes that with a week at the ski tunnel at Slovenia’s Olympic Sports Centre Planica, which appears to occupy one story of an otherwise functional parking garage. By the time people are literally flying halfway around the world to ski in 80-second loops inside a parking garage, it’s clear that off-season snow is special to everyone.

As Chelsea Little previously wrote in a lyrical piece on FasterSkier, she clings to the idea that, “at any given moment, somewhere in the world, there’s great skiing. If I can’t be back home and if it’s not December through March, then a corner of my mind is occupied wondering where that snow is and whether I can get there.” For Swenson, Husaby and a handful of other elite American skiers throughout the 1990s, the answer to “where the snow is” in October and November was consistently Fairbanks, Alaska.

- 1996 races

- Adam Verrier

- Alaska

- Audun Endestad

- Ben Husaby

- Bend Endurance Academy

- Birch Hill

- Carl Swenson

- earliest FIS race

- Fairbanks

- Fairbanks Daily News-Miner

- FIS

- history

- Jason Cork

- John Bauer

- Ken Leary

- Laura Wilson

- Marcus Nash

- Nanook Challenge

- Patrick Weaver

- Scott Loomis

- Suzanne King

- Todd Boonstra

- Wednesday Night Race Series

Gavin Kentch

Gavin Kentch wrote for FasterSkier from 2016–2022. He has a cat named Marit.