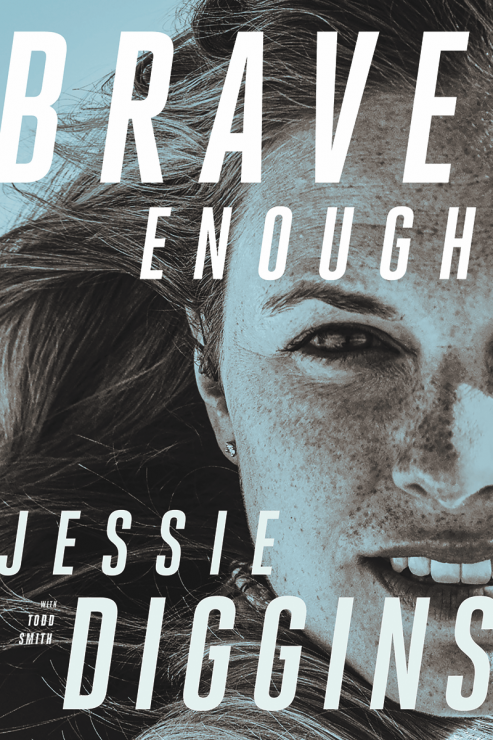

There are certain precepts that permeate Brave Enough, the new memoir by Jessie Diggins: Teamwork is good. So is glitter. Self-belief is important. Training hard pays off. As for substance, I have nothing snarky to say about these morals; nordic skiing, if not the entire world, would be better off if we all felt these things so fervently, and it is engaging to trace the development of these themes in Diggins’s life.

But as for literary merit, Diggins’s book is a whole lot more interesting when challenging things happen. I still think you should buy this book and read it; it’s written at a sufficiently general level that it will appeal even to non-skiers, but if you’re reading this website you’ll likely purchase it no matter what I say. But just don’t be surprised if you remember the work’s tumultuous middle more than either its adolescent beginning or even its Olympic ending.

* * *

Diggins’s book may be roughly divided into three parts: her childhood; her struggles with an eating disorder; and her professional ski career. The first and the third parts are about what you would expect. The middle part is searing, and by far the most compelling writing in the book.

First things first. Diggins enjoyed a childhood both bucolic and ideal. She grows up in rural Afton, Minnesota, in a house a half-mile from the nearest neighbor. She frolics through the woods unaccompanied, looking for fossils in the summer and building snow forts in the winter. She watches her father, from whom she inherited her race face, compete in Grandma’s Marathon and the Twin Cities Marathon and, of course, the Birkie, and she joins the Minnesota Youth Ski League at age three. Eventually, she joins the ski team at Stillwater High School, an inclusive community where “everyone was welcome, regardless of size, strength, or previous experience.” She gradually progresses from just wanting to make new friends to winning every race, while being welcomed by a team that embodies “the Stillwater way.”

This all makes for a wonderful childhood, one that every child should be fortunate enough to have. It also makes for less than compelling reading. As a lived experience, Diggins’s pre-adolescence sounds amazing. As a work of literature, it is not as noteworthy as the sections that follow. “Happy families are all alike,” as Tolstoy famously put it; a memoirist recounting an effectively perfect upbringing faces an uphill battle. Diggins succeeds as well as anyone in making such events memorable, which is to say, imperfectly.

But then – *record scratch* – “I had everything in the world going for me,” Diggins writes of her senior year of high school, “and nothing to complain about. Which is why when I started to struggle with an eating disorder, I felt such shame. Why did I have this problem? I didn’t have any reason to have an eating disorder (so I thought).”

This may not make you remember much about Diggins’s childhood after you put down the book, but it absolutely begins to recuperate this portion of the memoir as a work of literature: Diggins felt so guilty about her eating disorder precisely because she believed that she had had such a perfect life to that point.

In unflinching detail, Diggins describes bulimia, stress, and the compounding pressures of being a high-achieving student as well as an accomplished violinist as well as one of the best junior skiers in the country. There is disordered eating, forced vomiting, lies to her family and friends, and, eventually, throwing up so hard and so often that she bursts a blood vessel in her eye. It is unsettling to read, and Diggins pulls few punches. This section must have taken courage to write.

At one point, Diggins writes, immediately after making herself throw up once more, “Suddenly, I felt nothing. I started to understand why people are alcoholics or addicted to drugs. Because the ability to suddenly feel nothing was amazing.”

This is compelling, if not searing. Whatever your views on Diggins, as a person or an athlete, it is undeniable that she feels things quite strongly. This is someone whose nickname within the U.S. Ski Team is “Sparkle Chipmunk,” who was once described by The Guardian as the team’s “ebullient talisman.” To hear her say that she enjoyed feeling nothing, and “quickly began to search for that numbing feeling again and again,” is chilling.

This portion of the book is superb. Diggins is not afraid to engage with uncomfortable truths, and to use her own experience as a lens through which to examine what it is like to live with, be consumed by, and then work to overcome an eating disorder. Diggins repeatedly emphasizes, to her credit, that eating disorders “don’t discriminate,” that “Skinny teenage girls represent only 10 percent of eating disorder victims.” But she also must recognize that an Olympic gold medal gives her outsize influence when she talks about disordered eating, and she ably uses the platform she has earned to stick up for everyone dealing with these issues who is not a “skinny white teenage girl.”

It would be far too pat to say that, once she learns skills to cope with her eating disorder, Diggins puts this out of the way and moves on to a perfect life as a perfect skier, not the least because she explicitly discusses later in the book the times she had to overcome the temptation to engage in disordered eating once more.

Rather, in the memoir’s third part, Diggins takes the reader on a tour through roughly seven years of her professional ski career, 2011 through 2018, culminating in a certain team sprint Olympic gold medal. If you’ve read this website before, you probably already know the general highlights; they include dominance on the domestic SuperTour, a quick promotion to the World Cup, anchoring nearly every U.S. women’s relay over the past decade, and the general rise of the American women’s team as a global force in nordic skiing. But Diggins makes sure to weave in some lowlights, including disappointing races, injuries, and overtraining that ultimately required two weeks’ complete rest in fall 2014, when she would otherwise have been building intensity to sharpen race fitness for the 2014/2015 World Cup season.

After seven years’ worth of training and racing highlights, the reader is left with a nuanced understanding of not just the results, but also of the process that helped Diggins get there. Process vs. results may be somewhat of a shorthand or buzzword when it comes to thinking about training for endurance sports; it also works.

And it works well for a piece of literature, too. The climactic scenes in PyeongChang have more resonance because of everything that preceded them, not only Diggins’s decade of unstinting striving but also Kikkan Randall’s decade of work before that. Diggins writes, poignantly, of seeing nearly the entire American team at the venue that night; there is a now-famous picture, which you have likely seen, that shows the depth of the Americans’ support on that cold Wednesday evening at the Alpensia cross-country center.

But much as Diggins writes, convincingly, that she couldn’t have done it without the team behind her, the entirety of part three underscores that she also couldn’t have done it without training her ass off for the past decade, either. We all know that nordic skiers train hard; you may read Diggins’s description of a typical training week (replete with heart rate zone data if you really want to nerd out!), then consider living like that for 11 months of the year, and see for yourself. You’ll probably get pretty tired before the year is up.

* * *

As noted, there are some good things that Diggins feels strongly about, such as hard work and teammates and dancing and Taylor Swift. But as a work of literature, the bad things frankly tend to make for more interesting reading. There is a set piece about traveling through middle-of-nowhere Russia in the dead of night, for example, that is finely rendered and darkly hilarious. There are descriptions about Diggins’s experiences in Sochi, both in 2013 and again for the Olympics, that are interesting and insightful. There is an unflinching portrayal of the aftermath of a rollerski crash that is painfully vivid, and a description of training with food poisoning that made me cringe, then laugh out loud. These all make for great reading; Diggins is capable of being a fine storyteller.

At the same time, it is telling to survey some of the things that are bad, in Diggins’s worldview. Doping is bad, but gets only a couple of sentences in a 276-page book. Climate change is also bad, but gets only a few paragraphs, scattered throughout the work. “President number forty-five” – she can’t even say his name – is very bad, but only in passing, and mostly serves to prompt a memorable (and hilarious) story about her experience breaking down in tears upon meeting the Obamas during her post-Sochi White House visit. (This latter episode also provides the memorable phrase, in reference to Diggins’s official White House visit uniform, “Spanx cummerbund.” You’re welcome.)

But the media? Diggins is decidedly not a fan of the media – and, if you’ll forgive the navel-gazing, this seems like a relevant topic for this website to explore in some depth. Diggins variously has harsh words for print media, for television media, and for any of “announcers, writers, or sports commentators [who] try to put words in our mouths and guess what we were thinking at the time we were in a competition.” She calls out a media rep for her own team who betrays an imperfect understanding of race tactics, writing, “It didn’t seem worth it to explain tactics and drafting or even spend energy explaining that how I skied [in the back of the lead pack] was on purpose.” Elsewhere, she writes, “Since I’m not a reporter, I have no idea what it’s like for them, reporting on race after race, trying to make each one stand out somehow with a character story.”

Ultimately, midway through the PyeongChang Olympics, Diggins gamely faces the media following her 3.3-second bronze-medal near-miss in the 10-kilometer freestyle race. Soon after, during the podium ceremony, she retreats to a secluded hallway underneath the stadium, cools down on a spin bike, and, alone in the dark, unleashes “a scream filled with pain and disappointment” into her jacket. “It was a scream that said, ‘I wish that what I had was good enough,’” Diggins writes.

Moments earlier, Diggins had stood in the mixed zone and told reporters for this website (among many other members of the media scrum), “I could not have gone any harder. … That’s a really good feeling to know you gave it everything that you had and more than you thought you could give. I’m really proud of today.”

Now, she writes, “I knew that I had truly given everything that I had. And yet, it still wasn’t good enough to earn a medal. That stung. So, far away from the TV cameras and flashing lights, I let all of my emotions out right then and there. Spinning in the dark, I screamed my frustration and loss into a balled-up jacket.” She adds, “Honestly, the pain of going through the media zone after the race was what did it. Because I had felt good about myself until I went through that zone.”

Obviously Diggins is allowed to tell the media anything she wants. But the episode nonetheless raises interesting questions about the nature of journalism, and the obligations of a professional athlete to speak with the media even after disappointing performances. Or, if she does speak with them (and let me be clear, I have no reason to believe that Diggins has ever blown off the media at any point in her ski career, Bolshunov-after-the-30k-pursuit-style), what, if anything, she “should” say about her frustrations. And also about the responsibilities of the media, and whether or not it is fair to ask a disappointed athlete questions like, “‘Tell me, how does it feel to know your hometown was watching?’” (to take one of Diggins’s unappreciated examples from the PyeongChang mixed zone).

As one contemporary meme put it midway through the Olympics, alongside an image of a man with clothespins stretching his face into an artificial smile, “When you come up short in your races, but your sponsors paid for sparkle, not human emotions.” Or, as Devon Kershaw more recently said (around the 21:00 mark of the linked podcast), “The media is there when you win, but it is a show, and this is entertainment, and I know it feels like a huge deal at the time, I know you’re super disappointed. … But it’s called being a professional. You just pull the glasses up, you look into the camera, or you look into the interviewer’s eye, and you say, ‘Today wasn’t my day. I’m really proud of the Tour I had; today I just fell flat and had a raunchy day, and I’m looking forward to resting and getting on with my season.’ … It’s your livelihood, right, and you have to answer the questions in the media. Of course people want to know how did you feel today, like, How does it feel to lose the Tour de Ski win, Johannes [Klæbo]. He doesn’t want to answer that question, of course not. But like I said, you’ve got to be pro.”

The first comment was undeniably about Diggins; the second clearly was not. But if you like skiing, and are anyone other than a current World Cup athlete and so necessarily follow it through the filter of the media, Diggins’s thoughts on the media, alongside the frankly cruel viewpoint expressed by the meme, should make you think about the interplay between athletes and media, and how it manifests in the information that you hear. I don’t know what the “answer” is, but I think that these questions are worth asking.

(I am pellucidly aware that I’m writing this for FasterSkier, the paper of record for this niche sport (which, by the way, Diggins at one point read, but no longer does, likening it, or maybe the comments section specifically, to “driving past a car crash…you know you shouldn’t look, but everyone somehow can’t help themselves”). My understanding is that Diggins, whom I have never personally interviewed, has at worst a neutral, and I think in fact a positive, relationship with this website. Go ahead and listen to some of her recent post-race interviews with Jason Albert or Rachel Perkins (here, say, or here); it seems hard to characterize this as an antagonistic relationship with the media, or as the media asking unfairly pointed questions. But you, as the reader, really get to be the judge of that.)

So what else is bad? There is a certain former teammate who is (other than Trump) the only true villain in this story. She actively uses Diggins’s eating disorder against her, falsely tells her that the national-team coaches had called to say that they thought her eating disorder made her “hard to handle” and “a burden to the national team,” and outright yells at her, “telling me I was a liar, that I was a fake person who only pretended to be happy, that I was a pathetic, bad person.” Ultimately, Diggins learns the truth only when she privately approaches Matt Whitcomb to ask him if this is true; he is appropriately aghast and tells her that this never happened; she leaves the CXC Team for Stratton soon after.

On a happier note, Diggins concludes, “The power of these old psychological scars scared me and made me realize how far-reaching the effects of bullying could be. I vowed to never, ever let something like that happen to another athlete on the same team as I was.”

* * *

Diggins began work on this book soon after the PyeongChang Olympics, she has outlined in a blog post, with the assistance of a professional author, Todd Smith. The book is, literally, an as-told-to production; she explains in the blog post that Smith came to Stratton for a week, during which time he “recorded something like 20 hours” of Diggins’s thoughts. Smith oversaw transcription of the audio, she writes, “then cleaned up my ‘um’s, ‘ahh’s and way too many ‘like’s, and hammered my stories into more readable chapter formats.” Diggins edited rough drafts of each chapter during spring 2019 before the work went through a final copy-editing process with the publisher, the University of Minnesota Press.

Diggins says of the finished book, “it sounds like one of my blogs that grew up and went to college,” which seems quite apt. Perhaps as an artifact of the work’s oral composition, her voice is superb. (Indeed, as Diggins wrote, “It sounds exactly like me.”) If you want to see for yourself, compare a random portion of the published book, a random blog post, and a random post-race audio interview. You will have no doubt whatsoever that all three come from the same person.

Although bad words do not seem to fall within Diggins’s typical on-the-record linguistic register, they occasionally feature within the book. There are a couple fuckings, a handful of shits, and multiple instances of kickass or badass (often applied to Randall). Some of the profanities come in quotations from others, and certainly none is gratuitous. But I thought twice before handing the book over to my fluent-reader, hero-worshipping seven-year-old ski fan for this reason (okay, also the unflinching descriptions of the realities of an eating disorder); if you’re a parent you’ll know your own kids and can make your own judgment calls, but you may wish to keep that in mind. (As for substance, there is as much sex, drugs, or violence as you would expect from someone with a clean-cut Midwestern persona, viz., none. Save for that one time the police pulled a corpse out of the frozen river across from the team hotel in Rybinsk…)

There are a few other down notes in the book. One chapter turns on a somewhat forced metaphor about what is literally a box of memories, which as a literary device seemed strained. And Diggins’s wistful evocation of all the free time and unstructured schedules enjoyed by non-athletes, in perhaps a grass is always greener moment, falls a little flat. Ask anyone who is a parent, a recreational skier, or a person with a nine-to-five job (let alone all three!) if they really get to be done for the day at 5 o’clock, or stay up late without thinking twice about it. They’ll probably laugh at you, if they’re not too busy squeezing in a quick workout or driving their kids somewhere or helping with homework or making dinner or doing laundry or actually talking to their spouse at 10:30 p.m. before collapsing into bed.

Finally, there are a disappointing number of factual errors. The advance review copy that I received from the publisher referred to Diggins finishing 40th in the distance skate in Sochi and 12th in the sprint; she was in fact 37th and 13th, respectively. It says that Randall was 37 years old in PyeongChang; she was in fact 35. It says that Diggins won 13 races on the SuperTour in fall 2011; she in fact won nine. It said that the “entire team” was on course for the team sprint final in PyeongChang; at least one athlete was not, as witness this memorable live reaction video from an athlete watching the broadcast in the American gym. And it said that Diggins wants to be defined by more than just one Olympic race, and not be “forever falling back on those fourteen minutes on a Thursday night in South Korea.” But the race took just under sixteen minutes, and occurred on a Wednesday. I could go on (and could note that she has misstated even the year of her childhood Olympic-themed birthday party), but this gives a flavor of the type of problems I encountered – maybe not huge, but sloppy, and lots of them, enough to make me wonder what else in the memoir might be revealed as wrong if it were formally fact-checked. And don’t get me started on the outright typos.

None of these misstatements had been corrected in the final version of the book, and while some of the typos were cleaned up, more slipped through than should have. It is disappointing to find such errors in a work published by a university press, which was edited three times and gone through, Diggins writes, “line by line, word by word.” (To be clear, I don’t begrudge an athlete with hundreds of race starts to her name for not remembering all details of each one with eidetic clarity. I do, however, expect her co-author, or her publisher, or someone involved with a well-regarded university press to have fact-checked the thing, as well as to have ensured that there were no typographical errors in the final product.)

On a more amusing note, I should observe that Diggins casually name drops her myriad sponsors at only one point in the entire book, a chapter describing the PyeongChang Olympics. (“I like to put on my Bose headphones … I ate some Pro-Bar sports gummies and drank more Nuun endurance sports drink. … one of the awesome Salomon reps knocked the snow from my boots … I looked down at the palms of the gloves that I’d custom-designed with Swix.”) If this is a wry commentary on the implications of Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter, which effectively muzzles athletes’ ability to thank their personal sponsors at the one time every four years that they actually have a global media spotlight – and Diggins is too smart for this to be anything but – then it is a masterpiece of Midwestern-nice trolling from a universally beloved athlete. Well done.

* * *

It seems worth asking, perhaps more so for this book than for others, why the author took the time to write it. Writing a book isn’t easy, even with an as-told-to co-author, and many athletes training 800 hours a year do not undertake a book-length literary endeavor as a downtime bagatelle.

Indeed, consider that Diggins didn’t really need the fame; she has over 122,000 Instagram followers, who respond to her every pronouncement with reactions somewhere between affirmation and adulation. She likely didn’t need the money; she’s not as wealthy from this sport as she would be if she lived in Norway, where Johaug and Klæbo et al. have a ubiquitous advertising presence and lucrative endorsement deals, but she has earned hundreds of thousands of dollars in prize money, and in the acknowledgments she thanks her Chicago-based agent and his team for “years of helping me tell my story to the world with our partners,” which is not something you say if your parents are still funding your ski career. And she didn’t need to bolster her own image; she has a beloved reputation on two continents, and is a hero to skiers young and old.

The conclusion is likely that Diggins wrote this book because she wanted to, or, more specifically, because she felt like she had a story that she wanted to be told. If you care about Diggins, sports, or being yourself, I submit that her story is worth listening to.

* * *

The article has been edited to reflect the fact that it was Leo Tolstoy who wrote that “Happy families are all alike,” not Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Gavin Kentch

Gavin Kentch wrote for FasterSkier from 2016–2022. He has a cat named Marit.