Since 2011, Brian and Caitlin Gregg have been residents of north Minneapolis. They added daughter Heidi to the mix a year and a half ago. They are close to Theodore Wirth Park, an urban magnet for cross-country skiing with amenities like snowmaking, homologated trails, and mountain biking in the non-snow months. The Loppet Foundation, a local non-profit, was poised to host the first World Cup in the U.S. since 2001 until concerns and regulations associated with Covid-19 caused the event to be canceled.

Minneapolis has enjoyed a reputation as an arts and culture hub. The city skews left in its politics and serves as a gateway for Midwest winter sports. That image was shattered in the wake of George Floyd’s killing last month.

Like many places, Minneapolis was a reminder of how many cityscapes have historically been racist by design. Since the early 1900s, Minneapolis has segregated with the assistance of racially restrictive deeds called racial covenants. In other words, specific properties included language in their deeds preventing people of color from acquiring them.

In 1917, according to an interactive map titled Mapping Prejudice, we see a single property near the west side of Wirth with a racial covenant. By 1919 blue blobs on the map indicating impacted properties were viral near that location. Then in 1923, another cluster began to propagate adjacent Wirth’s northeast edge. As the map’s timelapse rolls into the postwar year of 1946, those two racial covenant clusters balloon. They defined the area for years.

Double click the images below to enlarge. Theodore Wirth Park is situated in the center of the respective maps.

Where the Greggs reside specifically in north Minneapolis is an area of the city that is predominantly African American. “You mention it to someone that you live in north Minneapolis and it is known as the not as nice part of town which we never really understood,” said Caitlin Gregg.

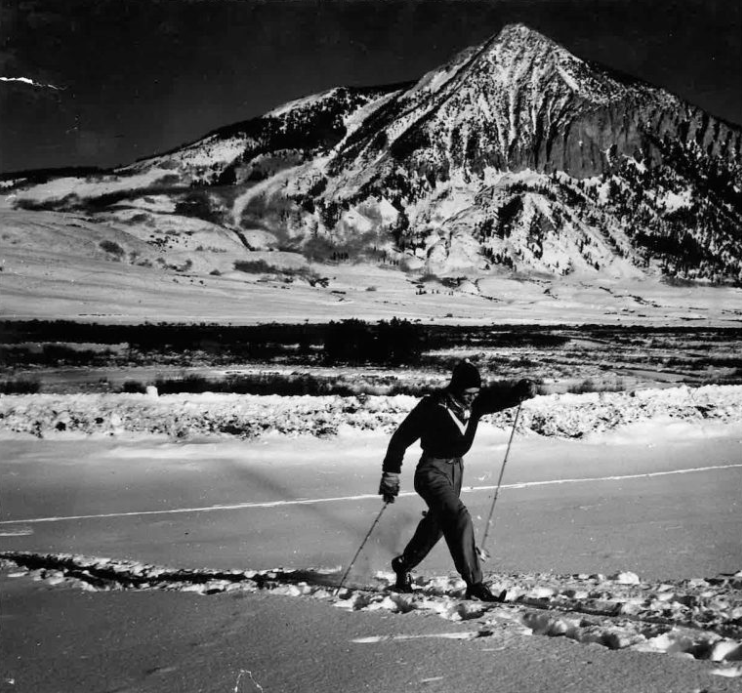

As they looked for a home to buy in 2010 and 2011, their budget was small. So were their needs. One-bedroom. One-bath. They didn’t require more. And location, location, location was a bellwether. Brian, a 2014 Olympian, and Cailtin a 2010 Olympian, desired close to home skiing. Wirth Park was their place. At the time, Caitlin worked for a nearby Boys and Girls Club and loved the neighborhood.

“’That is a bad area, what are you doing?’” was the often-heard response when informing people of their housing find said Caitlin. “And some of these are friends of ours for a long time. I lived nearby and I felt like it was a great spot for what we were looking for. I was willing to find out what the neighborhood was like for myself.”

Both for Cailtin, who spent the first 10 years of growing up in a diverse section of Manhattan, and Brian, who grew up in the bucolic Methow Valley in Washington, living true to their values is a constant. “We definitely stand out here and I think it is an experience that everybody should have,” said Brian. “In the sense that to walk into a room and be completely different than everyone else. Imagine what it would be like for a person of color to come to a cross-country ski race?”

The Greggs have worked intimately with the Boys and Girls Clubs near rural Hayward and Minneapolis and the Parks and Rec. Department in north Minneapolis. They have also collaborated with the Loppet Foundation to make cross-country skiing, mountain biking, and running accessible to the underserved and underrepresented. Their journey helping others as professional skiers began when they became involved with In The Arena, an organization linking Olympic athletes with empowering youth.

Most training logs serve the purpose of cataloging training hours by specifying items like time in zone, average heart rate, activity, and on and on. We’ve yet to see one with a column accruing time and energy given back. This is not to say many athletes have not found their cause and their voice; be it climate change, literacy, or eating disorders. The good work is out there.

It is a question being asked over and over by many pursuing excellence in nordic sport: “How is my cross-country skiing and my success in cross-country skiing helping? What is [it helping]? And how is that making the world a better place?” posed Brian as he explored how he and Caitlin have attempted to answer that question. “You have an immediate connection with people and in particular kids,” was one grounded response Brian gave.

Living in a community with omnipresent reminders of systemic racism and exclusion, the Greggs have spent significant time ruminating on their value as athletes and why they may be important to communities.

“One thing that athletics does is that it shows that setting goals and setting big goals, and setting goals that honestly may be the majority of people think are not possible,” Brian said. “You can inspire others to do the same, to define their next goals and best achievements as the ones that are not easy, and probably the majority of people thought you would fail at.”

Still, the constant stress of logging hours and resting adequately, and continuing the cycle, can be a deterrent to service and advocating for change. In the estimation of both Caitlin and Brian, however, their projects in north Minneapolis have made them better athletes.

“Whether or not we are better people I am not sure, but we are better athletes because of it, I think,” Caitlin said. “It gave us perspective and really realizing that we do love skiing and we do love pursuing our goals in skiing and we can do these things simultaneously. It does not have to be one or the other.”

Caitlin recalled the times she first worked with local youth, describing herself as wearing bright colored Lycra and goofy glasses, and some sort of ski hat. We know the look as the slowly evolving concept of cross-country cool as defined by those faster than us. Others know it as something sartorially disastrous.

“I thought, ‘oh my gosh is anybody going to want to listen to us or want to be part of something that we are going to do, we are just so different’? The most incredible thing that I have learned from working with the kids and the program that we aim to do is that it did not matter. That was a huge lesson for me,” Caitlin said. It really didn’t matter to them. The most important thing was that we were there and we were present. They could count on us. They could trust us, and we came again and again and again. And we cared about them and about what they were doing. And that was needed so much and it really gave me a lot of hope.”

None of this is to say the Greggs were not rattled with the recent marches and palpable anger in Minneapolis. Caitlin said it was simply unpredictable. Like others, they were advised to wet their fences to prevent potential fires from spreading and crack their windows at night so as to keep auditory tabs on what was transpiring outdoors. One morning after one of the most tumultuous riots to date in the city, Caitlin woke before 7 AM to the sounds of a small commotion. She went to the window with some anxiety, and saw one of the local kids, Joshua (9), zipping back and forth on his bike. He had asked his reluctant and slightly older sister to watch him – that was the grumbling Caitlin had heard.

“It was one of those moments, as if ok this is cool and good things in the world are still happening and will continue,” said Caitlin.

Joshua had learned recently to ride a bike. As a shy kid, it took him too long to convey to the Greggs that he didn’t know how to ride, but wanted to learn. Caitlin and Brian are known in their neighborhood as go-tos when it comes to how to access play in the outdoors. The Greggs helped secure a bike, and they were one degree separated from being Joshua’s human training wheels. Another neighborhood local, Jazir, who still swings by the Greggs daily, became a mentor to Joshua.

Jazir came into the Gregg’s lives as a gregarious neighborhood kid. Like Joshua after him, the Greggs rallied to help Jazir find a bike. He was eventually connected with the Loppet Foundation’s mountain biking program and his trail riding love affair began. With Joshua’s new prowess on the bike as evidence, Jazir has paid it forward.

Brian says their street near Wirth Park reflects the best of Minneapolis; a spectrum of people from all walks of life in close proximity to an urban jewel in Wirth Park. Caitlin, a trained environmental and city planner, said the city’s master plan called for a light rail system to connect their neighborhood with downtown and amenities on the city’s periphery. The original vision for the light rail would have blocked local access to Wirth. Through her involvement in the neighborhood association, Caitlin advocated for a modified plan allowing for easier park access.

The 2019 Theodore Wirth Regional Park Management Plan Analysis states, “Theodore Wirth Park values the mental and physical well being of their community and visitors and supports this by creating a safe, beautiful and fun environment for all seasons.” We all know it – easy access to open space is vital.

As the conversation with the Greggs waned, we didn’t touch on training or racing plans. I think we mentioned skiing once as Brian recalled a time deep in Wirth and deep in an interval session when a teenager he knew recognized him and called his name. It was an old neighbor named Quinn who was out skiing and had followed Brian’s 2014 Sochi quest. For the moment the Greggs are immersed in their full life and doing what they can to reflect and help their community.

There’s no doubt Minneapolis needs systemic change. If this moment is a tipping point, there’s optimism the city will be better off. It appears kids like Jazir and Joshua can keep Wirth local: the new light rail plan restores local entry points.

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.