This article provides an introduction to a series of interviews with professionals in sports nutrition and female physiology. Results from a survey regarding how elite US cross-country skiers and biathletes use insight into their cycles in their own training will also be analyzed and shared.

An arguably essential component of developing as an athlete is learning how to listen to the signals one’s body sends. Am I skiing easy enough on my recovery days to absorb the interval workouts? Am I dehydrated? Bonking and in need of a quick hit of carbs? Am I feeling mentally and physically flat because I have been stressed at work or lacking sleep?

In an ideal world, progress in skiing would be predictable. If I do X-Y-Z, my performance or technique will improve. However, the body is much more complex than a simple if-then statement. For female athletes, whose hormone levels fluctuate over approximately monthly cycles, this is especially true.

Before we jump into the nitty gritty of hormone levels throughout the menstrual cycle and how they might be considered in optimizing training and nutrition, I’d like to insert some anec-data to highlight the importance of talking about this issue.

Up until 2017 when my husband and I wanted to start our family, my understanding of the menstrual cycle was that it was roughly 28 days, PMS is generally unpleasant, and menstruating can be both uncomfortable and inconvenient. I thought of my cycle as two parts: bleeding and not bleeding, and I had never considered that there might be physiological changes throughout the cycle that might cause an ebb and flow (no pun intended) in my energy, moods, immune function, or nutritional requirements. In fact, had you told me that training and nutrition should be aligned with my cycle, I might have even scoffed, thinking I just needed to suck it up on the days I didn’t feel well.

In reality, that means 15 years where, despite trying to tune in on minutia of my technique and training to improve my skiing and running, my understanding of a fundamental body process I experienced regularly was all but nonexistent. This is not an uncommon scenario. And this is from someone who has a collection of books on training and performance and loves geeking out on exercise science research.

Through learning about female physiology and tracking my cycle in preparation for pregnancy and also following the birth of my daughter in October, 2018, I’ve identified a slew of patterns that help me feel more in tune with my body than ever. I also read the book ROAR: How to Match Your Food and Fitness to Your Female Physiology for Optimum Performance, Great Health, and a Strong Lean Body for Life by Dr. Stacy Sims, which I felt provided invaluable information regarding aligning training to the menstrual cycle and empowered me to experiment in my own training and life with positive outcomes.

Apart from training, understanding that the menstrual cycle is a window into your overall health is becoming more evident with research. The “Apple Women’s Health Study” — a partnership between Apple Inc., the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) — is currently analyzing a wealth of self-reported data to “demystify and illuminate menstruation and accord it the scientific scrutiny and social acceptance it deserves.” This comes in response to the fact that hormone fluctuations were long considered an uncontrollable variable that might skew scientific data, thus women were left out of experiments.

“In recent years, researchers have acknowledged the need to reevaluate the relationship of menstruation to overall health,” writes editor of Harvard Public Health magazine Madeline Drexler on the study. “Treating the menstrual cycle as a vital sign—comparable to blood pressure, temperature, pulse rate, and respiration rate—could lead to earlier detection of many conditions, both gynecological (such as fibroid tumors) and systemic (such as diabetes). Likewise, tracking lifestyle changes among those who menstruate—including the effects of body composition, activity levels, increased life expectancy, and postponement of childbearing—could help scientists glean factors that make an impact on menses.”

In addition to a canary in the cave for overall health, ROAR author Dr. Sims encourages women to understand that a regular period can be an “ergogenic aid”, i.e., a performance enhancer, that should not be avoided [1]. Yes, there are times when hormones might make us feel suboptimal. Wouldn’t you like to know why that is and what you might do about it so you can ameliorate your symptoms? That’s what this series is about.

To further the point that the menstrual cycle should not be thought of as a bemoaned inconvenience limiting female athletes, there is no evidence that V02 max is affected at any phase of the cycle, indicating that top performances in endurance events cannot occur at any phase. If it’s not holding back performance, but there might be ways to adjust your training to optimize adaptations throughout the cycle, why not learn more and begin paying attention?

Here is a brief primer on the menstrual cycle and what it might mean for female athletes. This information is intended to help female athletes and coaches understand the underlying physiological changes women experience throughout their cycle so they can adjust their training and nutrition to adapt accordingly, optimizing their training outcomes and performance over the long haul of endurance sport.

Menstrual Cycle Phases and Hormones

For the purpose of this article, we’ll focus on what is considered normal menstruation in a healthy female. Lack of a period, called amenorrhea, is well discussed in this podcast and will be addressed in subsequent parts of this series.

It is also important to note that while the fluctuations of hormones in a healthy cycle is well understood, conclusive evidence of the implications is still under research. While patterns have been seen in research, positive and negative effects of the menstrual cycle are largely individual. This information is intended to inform athletes of the body process to help kick start the process of learning their own unique patterns and responses.

The menstrual cycle begins at the onset of menstruation and lasts on average 28 days, though 21-35 days is considered normal. At its root, the menstrual cycle prepares the uterus for pregnancy, first preparing a follicle in the ovary to release a mature egg and thickening the lining of a uterus so that the egg, if fertilized, can be implanted and develop into a tiny human. If the egg is not fertilized, the lining of the uterus begins to break down and eventually is shed during menstruation, beginning the cycle anew. Note that high performance training is not included in that basic description.

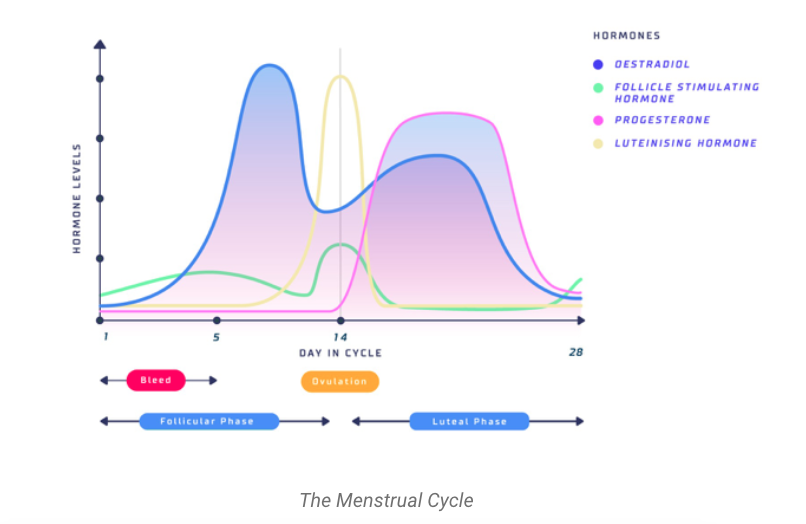

These processes are controlled by four primary sex hormones: estradoil (or oestradiol), which is a form of estrogen, progesterone, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and leutinizing hormone (LH), with estradiol and progesterone being the leaders [2]. Their changes in concentration divide the menstrual cycle into two primary phases, the follicular phase, which leads up to ovulation, followed by the luteal phase. These phases can then be separated into two sub phases of early and late.

To align with the information presented by the revolutionary FitrWoman App — which many see as the gold standard of cycle tracking for female athletes as it includes evidence-based insights from research in physiology, performance, and nutrition — I’ll refer to the progression from early to late follicular and luteal phases as Phase 1-4, which last roughly a week each [3].

As previously mentioned, phase 1 of the cycle begins when a woman’s period begins. In this phase, estrogen and progesterone are both low while testosterone (yes, women produce that too) is at an average level. This combination can help many women feel their strongest, however, because the lining of the uterus is being shed, women might experience side effects from inflammation at the beginning of this phase, like GI upset or fatigue [4]. If experiencing the latter, it could also be a good time for shorter, more intense sessions with plenty of rest in between, rather than longer threshold workouts.

In phase 2, estrogen begins to rise while progesterone remains low. Estrogen is a steroid hormone, which is linked to increased muscle mass and strength, as well as bone health [5]. With testosterone also at its highest, this can be a sweet spot for a hard block of training. Many women experience increased pain tolerance and decreased recovery time during this phase, and positive moods and mindset are also most common. The increased levels of estrogen may also promote stability in blood sugar levels, helping athletes maintain their energy levels during training. This could be a time to ski hard and ride the endorphin high!

Phase 3 begins when ovulation occurs. After a spike in LH and FSH to initiate ovulation, estrogen drops rapidly, then begins to rise again while progesterone steadily climbs throughout. The elevated levels progesterone causes a rise in body temperature of about 0.3℃ or 0.5℉, which may influence hydration requirements and make it more challenging to regulate body temperature if training in the heat [3, 1]. Breathing rates and heart rate also increase both at rest and during exercise, making training feel a bit harder, and blood sugar levels may be less stable, placing a higher demand on carbohydrates during training and increasing the importance of balanced meals that include fiber, healthy fats, and protein to help keep energy levels and appetite predictable [2].

In the fourth and final phase, both estrogen and progesterone drop to their lowest levels of the cycle. This rapid drop is linked to the symptoms commonly referred to as PMS, which include GI distress, bloating, headaches, moodswings, and fatigue. These symptoms are likely due to an inflammatory response triggered by the lack of hormones, which continues into Phase 1 as mentioned previously. You read that right. When you have PMS, you’re not “hormonal” — you’re actually un-hormonal.

From a training perspective, this inflammation may make it harder to recover from hard sessions, leaving you fatigued on top of other PMS symptoms. It may be possible to reduce these negative feelings by eating anti inflammatory foods, like berries, nuts, and fish, and avoiding processed and high sugar foods that are thought to exacerbate inflammation.

To be clear, some women experience very mild, if any, impacts from their hormonal fluctuation. However, if this is something you’re curious about or you feel your energy levels and appetite do not always match your expectations based on your training schedule, this might be something that could help you feel better throughout the month, in and out of training.

Conveniently, the “three weeks up, one week down” general guideline of training — meaning three weeks of building volume and/or intensity, followed by a recovery week — already aligns well with what FitrWoman recommends in terms of experimenting with aligning training to the cycle. During Phases 1 and 2, progressively build and increase loading during strength sessions. In Phase three, consolidate, meaning longer recovery between sets of intervals, or perhaps lower weight with higher reps in the gym.

Then, in Phase 4, rather than pushing through while feeling suboptimal, back off on the intensity sessions and include additional easy or rest days to absorb the previous three weeks of training and give your body the extra recovery it might need.

Want more? The team at FitrWoman hosted an informative free webinar in February 2019 on Facebook featuring Senior Sport Scientist and elite marathoner Dr. Georgie Bruinvels. The webinar is still available here.

Sources:

[1] Sims, Stacy T. Roar: How to Match Your Food and Fitness to Your Unique Female Physiology for Optimum Performance, Great Health, and a Strong, Lean Body for Life. Rodale Books, 2016.

[2] “What Athletes Need to Know about the Menstrual Cycle.” FitrWoman, www.fitrwoman.com/post/lgfa-webinar.

[3] Beverly G Reed, MD and Bruce R Carr, MD. (August, 2018). The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. www.endotext.org

[4] Solli, Guro & Sandbakk, Silvana & Noordhof, Dionne & Ihalainen, Johanna & Sandbakk, Oyvind. (2020). Changes in Self-Reported Physical Fitness, Performance, and Side Effects Across the Phases of the Menstrual Cycle Among Competitive Endurance Athletes. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance.

[5] Chidi-Ogbolu, Nkechinyere & Barr, Keith. (January, 2019). Effect of Estrogen on Musculoskeletal Performance and Injury Risk. Frontiers in Physiology.

- aligning training with menstrual cycle

- female athlete physiology

- female athletes

- Female physiology

- menstrual cycle

- menstrual cycle and performance

- ROAR: How to Match Your Food and Fitness to Your Female Physiology for Optimum Performance Great Health and a Strong Lean Body For Life

- Stacy Sims Ph.D

- stacy sims ROAR

- training female athletes

- training with menstrual cycle

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646