The decade of the aughts witnessed the decimation of wide swaths of forest in Colorado due to a pine beetle infestation. This was no slow drip affair. What was a tree-to-tree process eventually swallowed whole green mountainsides morphing them into a desiccated dead-tree blight. Those dead trees, unable to hold moisture, were hundred-foot matchsticks during wildfire season.

Over the past few decades, an ominous cycle prevailed. Warming temperatures due to climate change made life easier on pine beetles. Drought made for more combustible forests and extreme wildfire danger. Across the West, cross-country ski areas rely on trees for shade to prevent premature snowmelt on trails. They also serve as wind blocks in mountain-scapes prone to winds. Trees are a skier’s friend when considering trail design, maintenance, and longer ski seasons. Some die-hard skiers might know the climate data suggests winters are becoming noticeably shorter.

Skiers in Colorado’s Winter Park-Fraser Valley were witness to the pine beetle kill and its inexorable apocalyptic roll. If you skied at Snow Mountain Ranch or Devil’s Thumb during this era, in a few winters, much of the forests constituting those ski areas died off.

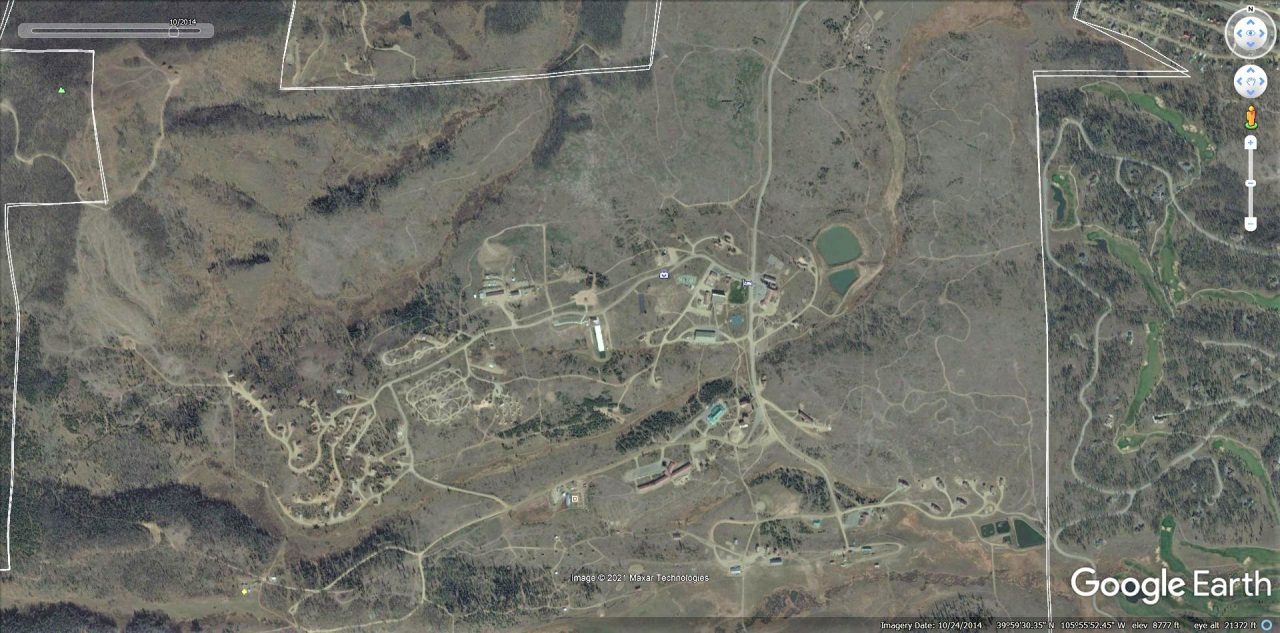

According to Devil’s Thumb Ranch, the kill became apparent in 2005. A larger outbreak in 2007 impacted much of their lodgepole pine. The same was true for Snow Mountain Ranch. The two areas are separated by eight miles or so, as the bird flies.

Forest conditions across much of Colorado, and certainly in the Fraser Valley, were ripe for wholesale die-offs due to the beetle – it was a perfect storm. Leading up to 2005, Colorado had suffered several drier than normal years. Warmer winters also allowed the beetle to persist: beetles are often killed off by long-duration cold spells of below 20 degrees Fahrenheit. Beetles survived the winter, as they continued their life cycle. Trees were stressed, making them more susceptible to contagion.

Compounding these variables were fire mitigation practices that promoted unnaturally dense forest. The forests, like much of the timbered land in the West, were managed in a way that suppressed any fire that might potentially rip through and naturally thin it. Dense forest made it easier for beetles to do their thing, and with the now browned forest, the threat of wildfire intensified.

What ensued was wholesale landscape change. Rust-orange trees, not green lush forest, became the backdrop for skiers. Both Devil’s Thumb and Snow Mountain Ranch had to act. Their assets, trails, buildings, and a back-to-nature experience were threatened by the possibility of tree blowdown and fires.

Both areas logged heavily to remove potential fuel sources. Devil’s Thumb used some of their beetle-kill timber as they built new outbuildings and housing.

“We did have industrial level logging that we had to do around 2006 to around 2010,” said Mary Ann Degginger, the Program Director at Snow Mountain Ranch. “We started first with the front of our property just to take out the dead trees and leave the younger healthy ones because there was some research out at the time that said, pine beetles were driven towards trees that were four inches or diameter or bigger – so we left the little trees. They didn’t bother them. And what we found is that because of the nature of pine trees and how they grow, they have very shallow root systems, that they just blew over naturally when we logged around them. The trees we tried to leave ended up dying anyway or falling over.”

Massive piles of logs built up around the outbuildings at both ski areas. It resembled a full-scale timber operation. Saving trails and ski terrain remained paramount, but bigger issues remained – creating a resort environment where physical assets were not threatened by fire.

“We had to prioritize from a fire mitigation standpoint — our whole property and operation,” said Degginger. “We determined where we needed to log first. For us, that meant protecting buildings and common areas. Once we felt that we had done that, we moved on to mitigation and cutting trees along our trails.”

Degginger explained that Snow Mountain Ranch created a buffer along their ski trails as the next step in their risk mitigation plan.

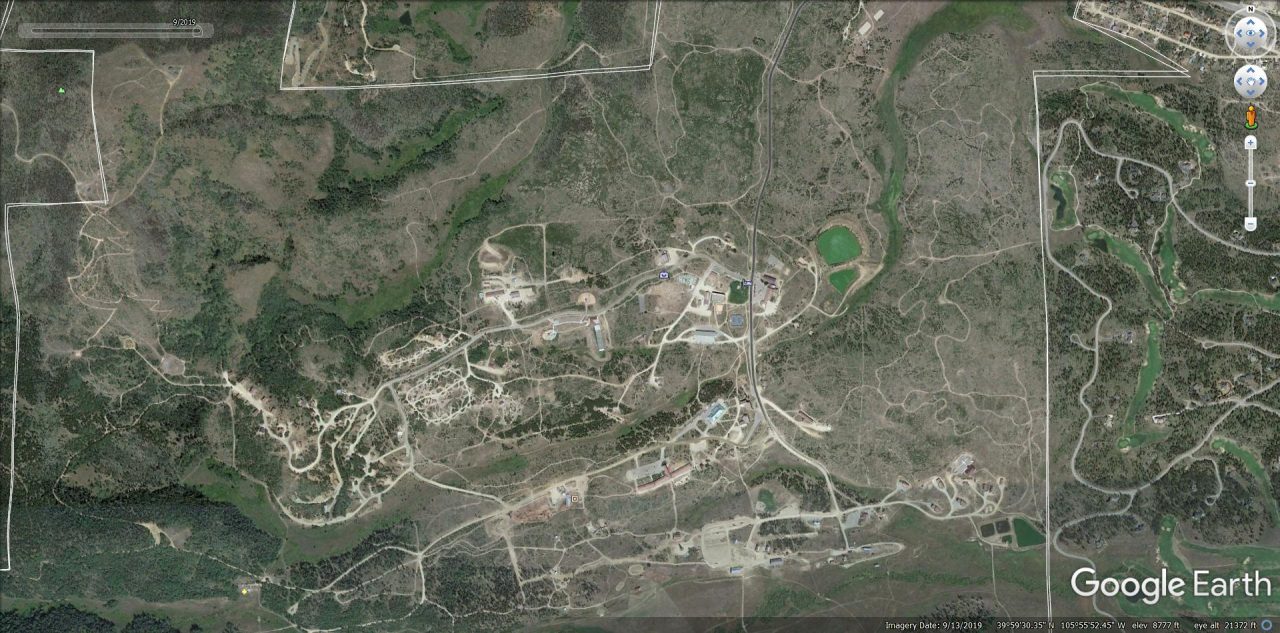

A decade later, forests in the region have renewed. Areas of new tree growth have allowed the return of a natural windbreak. And in some places, Snow Mountain Ranch has begun grooming trail sections once lost at the onset of the infestation.

“We’ve learned a lot since 2005, starting with the process of thinning, removing, and harvesting dead beetle kill,” emailed a representative from Devil’s Thumb. “We also cut some of the green timber to allow sunlight for the growth of healthy trees and to prevent greater damage/falls during windstorms.”

The past few summers in the intermountain West have witnessed a conflagration. In June 2007, hundreds were evacuated from Snow Mountain Ranch due to an encroaching wildfire. In 2020, the area witnessed two historic fires. Snow Mountain Ranch ultimately served as a camp for firefighters battling those blazes. The point remains, fires remain a risk as they burn hotter and bigger than in the past.

All this leaves ski area managers broadening their scope of expertise. There’s still the marketing and soft goods to order pre-season. But there’s also the responsibility of understanding fire risk, holistic forest health, and planning long-term for cyclic variability that might impact a ski area’s bottom line.

Resources have been allocated across the West for forest thinning projects. Here in Bend, Oregon a multi-year thinning project has transformed the overly dense Ponderosa pine forest. To new eyes, the change was stark. Yet after only a few months, with ground fuels reduced through controlled burns and selective tree thinning, more appropriate spacing between trees was re-established and native grasses returned. Locally, there was no wholesale beetle kill or wildfire that decimated the city’s nearby forests — but that was only a matter of time. Stakeholders got ahead of the inevitable firestorm. The recreation economy in places like Bend and Grand County, Colorado where Snow Mountain Ranch and Devil’s Thumb reside, rely on healthy and intact forests. The overriding philosophy now is to be proactive with forest management.

That’s the case at Snow Mountain Ranch and Devil’s Thumb. These two iconic Rocky Mountain cross-country ski areas are better positioned to weather environmental changes with buildings and ski trails intact. Snow Mountain Ranch’s Degginger understands that as the new forests surrounding the Snow Mountain Ranch complex matures, new, but smaller-scale thinning will take place. The eyes are on the future in the Fraser Valley.

“We need to manage this forest better and not be in the same position,” said Degginger. “So that’s certainly something we are taking expert advice on. We’re not quite to the point where we’re thinning yet, but that’s on our radar, that’s something that’s going to need to happen for the forest that receded naturally and came back super thick and super. We don’t want to be in the same boat 100 years from now.”

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.