In speaking with representatives from each of the leagues featured in this series, a few main points rose to the foreground in this discussion: the level of competition matters, how the policy came about matters, and how a program can enhance athlete support holistically by relieving wax-related expenses – measured both in time and dollars – matters.

Before jumping into discussions for club level programs across the West, here are the links to view the details of each wax policy specifically: Intermountain Division (IMD); Rocky Mountain Nordic (RMN); Pacific Northwest Ski Association (PNSA)

Also note that these conversations took place in late-April, prior to further discussions at the U.S. Ski & Snowboard spring congress sessions in May where subsequent conversations among leadership may have occurred. Should significant changes occur, FasterSkier will continue to follow the story.

Here are links to earlier installments in this five-part series. The first two parts (part one; part two) spoke to the perspectives of high level wax technicians and industry representatives, while part three focused on the Wisconsin Nordic Ski League.

The Evolution of Western Club Wax-Protocols

There’s a lot to unpack surrounding the impact of wax policies on the sport, and it is not reasonable to project that what makes sense for junior club programs can be extrapolated to the sport as a whole, which includes everything from the recreational level to masters racing to the World Cup. However, as a major player in the U.S. development pathway and a collective that encompasses a large volume of the nation’s athlete base, considering the evolution and impact of wax policies at the club level provides valuable insight into what the objectives and outcomes may be more broadly.

Conversations on this subject began long before any official policies were accepted, and their initial aim was to uniformly address the use of fluorocarbons at Junior National Qualifiers (JNQs). With both the health of athletes and coaches, and the inequity of buying power among clubs, the goal was to reduce spending and expensive fluorinated top coats.

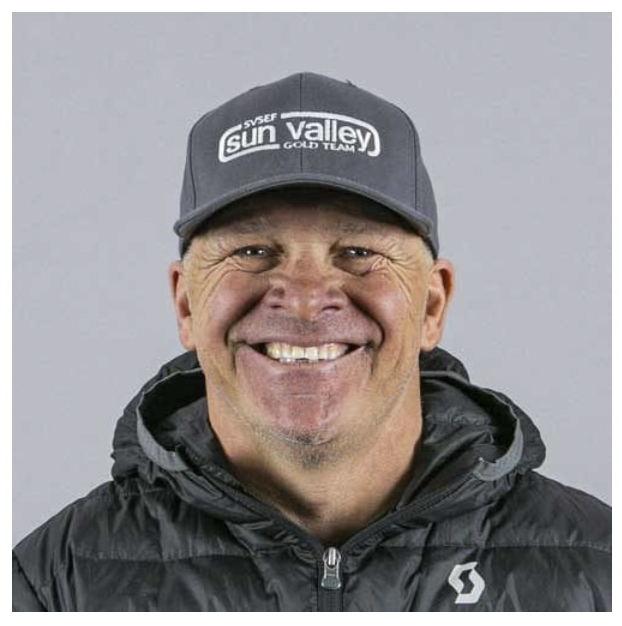

Timelines are now blurred, but long-time Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation Program Director Rick Kapala indicated that Rocky Mountain had perhaps been the division who got the ball rolling. Though the policies have since converged on a single wax call made in advance by host coaches depending on forecasted conditions, Kapala explained that at the onset, Intermountain’s policy was only focused on the elimination of pure fluoros.

“Initially, Intermountain had what we could call ‘wax policy-lite’… Our policy was: you can use any wax as long as it wasn’t pure-fluoro. You can use a high-fluoro, a low-flouro, or non-fluorinated version, and of course, in different brands, that meant different things. But basically, we went for a number of years with a no powder, no liquid and no rub-on policy. And that had some effect on trying to mitigate the arms race, if you will.”

Executive Director at Methow Valley Ski Education Foundation Pete Leonard explained that the Pacific Northwest Ski Association, for whom he is the Nordic Director, was developed with a similar progression.

“It initially started in the fluorocarbon era, moving away from powdering skis to just having blocks and liquids – the top coat type of applications – and then to a base paraffin application… I think we had a year of that and then [the policy] went to fluoro-free – the same basic, simple base paraffin called several days out.”

Further motivation to align policies stemmed from “cross-pollination” between these three leagues, which with the addition of the California-Nevada Far West division and Alaska, encompass the Western region as defined by U.S. Ski & Snowboard. In particular, these divisions overlap during the Junior National Super Qualifier Event held in January at Soldier Hollow, hence landing on a very similar model.

“There’s a little bit of a cascade effect, and it’s just simpler for us to match what IMD has,” Leonard explained.

Kapala felt strongly that it was important to emphasize that this slow progression happened organically, which he felt was in stark contrast to the Wisconsin Nordic Ski League, where a sponsorship proposal made by a corporate entity included stipulations on waxing at league events.

“It’s a wholly different thing when a grassroots community, like a bunch of clubs in a division, promulgates a policy that they think results in the best athletic outcomes,” he said. “And it is very important to differentiate the genesis of a given policy… the order in which you arrive at a policy really informs a lot of the motivations about why you’re doing what you’re doing.”

Kapala said IMD would have “given the Heisman” to a wax company that required a policy; however, Swix products have been selected based on trust in the availability for all programs.

“We settled on Swix without getting into the specifics of brand value,” he said. “I.e., Swix is better than Start, and Start is better than Toko, or whatever – it’s just simply because virtually everybody knew they had enough access to that wax.”

Observed Program Benefits

There’s a sizable jump between eliminating fluoros and further reducing a wax box to a small array of products, but Kapala emphasized that these “athletic outcomes” are the central tenet around which discussions regarding changes take place within Intermountain. How does the protocol impact the opportunity and capacity for athletes from clubs of all sizes to be successful on race day and have a positive experience in the sport?

We’ll start with the impact to a program’s budget, which on its own is a source of inequality among clubs in a given region. Speaking specifically for Intermountain, but also the West more broadly, Kapala pointed out that there are a number of “super clubs” whose financial means and staff power made it hard for smaller clubs to compete in an open wax environment.

“They’re usually clubs that are in these mountain towns that are part of [larger] ski foundations or clubs that are multi-discipline, really big clubs. And so they have a lot of administrative function, a lot of underpinning financial security, and so on.”

He was quick to include SVSEF in that pool, saying cost was not a primary concern when it came to his wax purchasing or race staffing prior to the enactment of IMD’s policy.

He went on to explain that within Intermountain, there are six JNQs which are subject to the wax policy, plus an Intermountain opener. However, what he called the “lion’s share” of races, including U.S. Nationals, SuperTours, and any Canadian-based races, remain open wax events where the policy does not apply. Still, with IMD’s policy in place, Kapala said SVSEF has been able to shave $5,000 dollars annually off its spending on wax, equating to a reduction of 30-40%.

“The question then is: ‘What am I doing with that $5,000?’” posed Kapala. “Well, what I’m really doing with it now, in my particular case, we have put that money into our merit scholarship program. So instead of me spending money on just making sure I have every wax in the universe in my wax box, I’m actually leveraging those dollars to help kids get to training camps or to go to competitions they wouldn’t normally be able to afford. And that’s huge.”

Rather than ignoring the impact this reduction in spending has on the landscape for suppliers, he acknowledged that this could be detrimental, as other clubs are likely reducing their spending by similar percentages. But bringing the focus back to the athletes, he said, “what we’re really spending less of is human capital on things other than coaching.”

For Kapala, this makes the cost-benefit analysis check out.

“We think being available to coach kids – that are especially young in their developmental process – at events like JNQs, is actually what the [coaching] game should be all about. So while it’s true that there can be impacts regarding the finances, it is also undoubtedly true that athletic outcomes – true athletic outcomes, the actual ones that we should be concerned about – are actually being serviced way more effectively. And if those two competing interests are both true, we have to pick one. And the one we’re picking is we’re making it more fair for athletes.”

Speaking for what he has observed within his own program and the Rocky Mountain Nordic division more broadly, August Teague – Cross-country Program Director at the Aspen Valley Ski and Snowboard Club (AVSC) – shared similar sentiments.

“I guess the real question to me becomes: ‘What is the purpose of a waxing protocol and at what level and why? And I certainly believe that barriers to entry in sport are a real good reason to have a waxing protocol, and time allocation or time management.”

Adding specificity to the statement, he said, “The biggest thing that I see is that I can spend more time coaching instead of teching. And there certainly is an argument as to the need for better wax techs both from this country and elsewhere, but I think that’s a separate discussion than the coaching discussion and where my time is best served.”

While the AVSC nordic program is significantly smaller than that of SVSEF, Teague also noted differences in how his monetary budget is allocated. “We have started to explore structures more than we ever have. So money that was being spent on product is now being spent on different structure devices and/or ways to test that structure.”

Similarly, Steamboat Winter Sports Club U16/U18/U20 head coach Josh Smullin wrote to FasterSkier that the protocol has supported a safer environment for both coaches and athletes while on the road. In particular, he cited driving – there are roughly 3,200 serious injuries and 600 fatalities on average annually in Colorado – as a place where some relief in the toll on coaches during a race weekend has shown value.

“It used to be that we coaches were up late waxing,” he explained. “Waking up the next morning to go set up at the venue, and then would drive many hours home after the race. A waxing protocol has helped us to be safer drivers, less sleep deprived, and more present with the athletes.”

Smullin also commented on ventilation, which remains important for the health of waxers even without fluorinated products.

“At many of our home clubs we have some sort of ventilated wax facility. We do not have that on the road [while staying in hotels] unless the weather is nice and we are able to wax outside. Regardless of the fluoro ban, [proper] ventilation is healthier for coaches and athletes.”

“Everybody’s got their opinion…” said Leonard on behalf of PNSA. “There’s no overarching study on these things, and costs, and whether there’s a major difference [in ski speed], but I think what is clear to the coaches is that there’s less time spent testing glide products at races and there’s less of an incentive to do that, especially with the calling it [a few days] prior. There’s also more time that they can focus during that weekend on other things, like with the athletes and their preparation, instead of testing wax, waxing skis and leaving [coaching and direct athlete support] right up to the race time.”

For Leonard, the question of whether the policy widens the gap for skiers based on the quality or condition specificity of their skis was not a priority when it came to identifying how the policy has served PNSA teams. For a club based in the Methow Valley which travels to regional competitions across Oregon and Washington, as well as to the Super Qualifier in Utah, the policy has reduced the toll of travel.

“I don’t know that it’s necessarily a parity – it’s really difficult to get that down.. but I think for us, calling the wax several days out just makes it simpler for people, and there is less [equipment and product] to travel with, one less thing to think about when you’re booking hotels, and all those details. It makes it simpler for teams.”

He said he has also found it quicker and easier to apply structure on race day without the variable of glide wax testing. And without the need to cart around as much product and equipment, getting his athletes’ skis race ready has been “way easier to manage”.

He said he has also found it quicker and easier to apply structure on race day without the variable of glide wax testing. And without the need to cart around as much product and equipment, getting his athletes’ skis race ready has been “way easier to manage”.

“Rather than bringing a wax box with several waxes in it, irons, enough benches that you can get your whole team through, scrapers, brushes, etc. – already, you’re packing the van to the ceiling and then, sometimes it’s driving eight hours, or for the Super Q for us, it’s driving four hours to the airport, [hauling our skis and gear through the airport on both ends], then driving another hour-plus to SoHo, and then doing it all again on the way back.”

Stay tuned for the final installment, where you can read more on leveling the playing field, the arms race (or lack thereof) for skis, and the reception among Western Division coaches.

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646