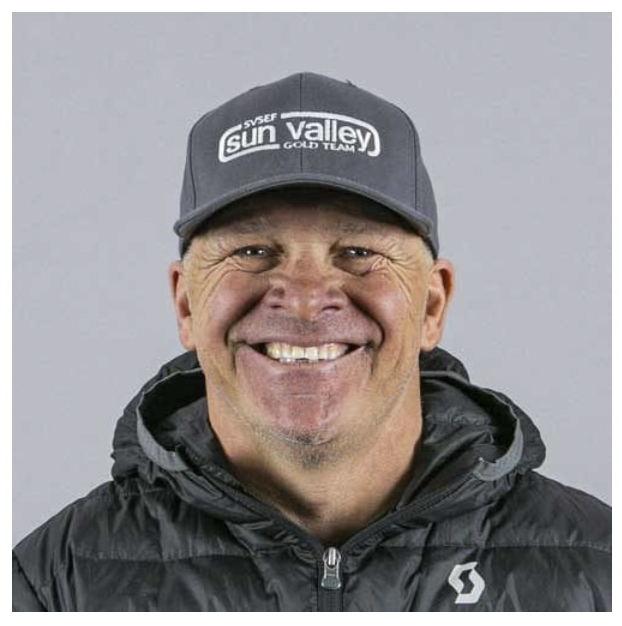

“I’m sorry, but once I start talking cross-country skiing, I can’t stop,” admits Rick Kapala. Remove the “talking” from that statement, and it’s still a succinct summary of long-time Sun Valley coach Rick Kapala’s career.

This season will mark the first time in thirty-five years that Kapala won’t be manning the wax bench on race day for the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation. This summer, he turned to a new role at the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation with the title “Sport Development Director.” In his stead, former Bates College Coach Becky Woods will take over his former Program Director duties.

For those who have known Kapala during his long tenure in US skiing, his new title signals an exciting prospect. Kapala has been a constant, forward-thinking mind in US Skiing. He has played a role in creating a domestic professional skiing scene, helped start the National Nordic Foundation, and counts a plethora of key figures in US Skiing as his former athletes, coaches, and mentees.

FasterSkier caught up with Kapala to reflect on his own journey to this point and get a glimpse into some of the most exciting ideas pushing US Skiing, from one of its most passionate minds.

(This interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

FS/FasterSkier (FS): Let’s start with your biography as a coach. Can you give us a summary of your career as a coach and at Sun Valley?

Rick Kapala (RK): Coaching for me started at my alma mater, Michigan Technological University (Michigan Tech), the year I graduated. Then I moved out west and I coached for a couple years in Washington state at a club program run by Pacific Lutheran University.

Then I moved to Anchorage which was where I was really fortunate in my timing. I landed coaching at West Anchorage High School as their ski coach, track, and cross-country coach. And the stable of athletes I had there was full. Nina Campbell, Joey Caterinichio, and Chris Grover are just a few your readers might know. I was really lucky that was my first exposure to sort of an “all-in” type coaching job. Then I came down to Sun Valley in the summer of 1987 and have been here ever since.

FS: What did the Sun Valley team look like when you got to Idaho?

RK: We had a pretty good little program, this being the ski town that it is. The Alpine program was big, but the cross-country team was this small, ancillary program. We had seven to nine on the high school team, and then seven or eight middle schoolers.

FS: How did you approach building out that program back then? Was it adding a younger development program? Bolstering numbers for the high schoolers?

RK: There was a separate, kind of “Bill Koch League” (learn-to-ski) type program in the Valley. We assimilated that and made it our Devo program under the umbrella of our offerings. The program immediately began to grow from there. I attribute that to having really good coaches at that younger age who were really invested in the right way over the course of the first four or five years I was in Sun Valley. That eventually led to steady growth for the Comp (high school) program. That model is the basic infrastructure of a club. The same can be said about New England with the Bill Koch League, or in Minneapolis with the Minnesota Youth Ski League. Really dedicated coaches at the younger level are what end up powering competitive programs.

FS: At what point did Sun Valley grow beyond the junior programming? When did the Gold Team (Sun Valley’s Pro Team) and Post-Grad programs start to develop?

RK: The genesis of the Gold Team was a really fortuitous set of circumstances. We had a great coach, Chris Grover (who Kapala had coached at West Anchorage), landed in Sun Valley after the Nagano Olympics in 1998. He had been with the national team, but at the time there were budget cuts. Grover, coming off of that, had a pretty profound instinct that skiing couldn’t just develop within the [United States Ski and Snowboard Association]. He came to me and said, “we should start a pro team [in Sun Valley],” which, in retrospect, was such an important development because it allowed us to imagine a whole new ecosystem for our programming.

Having Grover come off of the national team also made it an easy prospect to get athletes here. Chris Cook, for example, got cut loose from the national team, and Grover was able to step in and give him an obvious avenue to keep pursuing professional skiing. That was key—having an avenue to go down. Cook won a national championship the first year he was at Sun Valley, and then made it to the Olympic Games.

That was a part of the fortuitous nature I talked about too. That the next Olympics were in Salt Lake City [in 2002]. The Gold Team was originally the Olympic Development Program—we got told eventually we couldn’t use that name, but it gave us a lot of visibility from the community here in Sun Valley, and a clear “brand” for talented skiers to know what they were pursuing here.

FS: What strikes me as interesting about that “fortuitous” timing is that there was a push around US skiing at the same time Sun Valley’s team got started to have those Olympic Development programs around the country, but most of them weren’t nearly as sustainable as Sun Valley ended up being. In the past few years, we’re seeing a renewed push to introduce more pro racing opportunities across the country, whether that’s Bridger Ski Foundation’s team in Bozeman, or Team Birkie in the Midwest. What are some of the things that have made Sun Valley sustainable that could help make those programs sustainable as well?

RK: Whenever I get a question like this, I always start with a disclaimer. Sun Valley is a really unique place that affords us some big advantages when it comes to building and sustaining new programming. We have one of the richest traditions of skiing in the country, and it is still a ski town—it hasn’t sprawled out in the same way that other places have. It is also a fairly affluent community.

The industry here is skiing too, that always is going to be an advantage. We have an outsized role in our community because of that. When we roller ski in the summer, people are cheering on our kids, that’s not happening in other places, right?

I think we have had to center our approach around the idea that we are a community asset here. We try to have success, just like any sports team, but what we are really trying to be is the highest-quality recreational and competitive opportunity for kids in our valley. That gives kids the resources they need to take skiing as far as they can. Whether that was Morgan Arritola, or now Sammy Smith and Cora Faye Scott. They all came through a program that at the start was really a way to get out and involved in our community and kept true to that impetus. Naturally, that is going to engender warmth and engagement from outside of just the ski community. There is also making sure that the talent that is coming through the Gold Team, for example, is able to invest in the wider community here. We need to make sure they have the chance to do that. And they have.

I am not saying the model here is the model everywhere. What the Loppet Foundation has done to make skiing the big deal it is in Minneapolis—that’s phenomenal—they figured out how to balance programming, events, and facilities in a way where kids might just want to go skiing on Sundays rather than watch the Minnesota Vikings play football. And not every kid will, but they have the option to and feel like it is worth it. That is so important.

Or in Anchorage, right, skiers are on the front page of the newspaper. That’s a big deal. It is the same in Sun Valley, and I think that speaks to creating a community ecosystem that celebrates and invests in skiing.

FS: I am struck by how the skiers that the Gold Team has a pretty consistent mix of kids from your junior program and from other programs across the country . . .

RK: That’s super intentional. There just needs to be a critical mass to be able to inspire and also, provide a high-quality training environment. Johnny Hagenbuch, right now, for example: when he got to a point as a junior, having the Gold Team for him to hop into for training made a big difference in his development.

FS: With regard to “development,” we haven’t covered your new position in detail. You’re moving from individual athletic development to a more club-wide role. What does that look like in Sun Valley, and how do you see what you’re doing in Sun Valley pertaining to US Skiing in general?

RK: Well first, I don’t want to say I have answers beyond the community here. I think keeping my focus here is really important.

My new position as “Sport Development Director” is multi-pronged. I’m still doing the resource development for the Nordic Team and coordinating events like the upcoming SuperTour. Then, there are a few other initiatives that follow along the lines of thinking, “what is the next thing?” in sport development. One of those is coach education. In our organization [at Sun Valley] we have about one-hundred coaches on the payroll during the season. Right now, the coaches certification process they go through is kind of transactional with US Ski and Snowboard, right? Meaning they take this coaches’ course and maybe do a continuing education credit, but that might be it. One thing I think is big incongruency in [American] skiing right now is that we work on cultivating a growth mindset for our athletes, but we don’t have the same mentality for our coaches, let alone the resources to make it possible. I think that’s where we need to go. Like Doctors have the American Medical Association, we need to have an organization—or use our existing organizations—to cultivate a culture of what I’d call “professional development.” As a ski community, we’re past the point where we are simply hiring people to coach based on the merits of their skiing. I think it is a positive development that it is a distinguishable profession, but now we need to do the work to not make it a profession where everyone is kind of self-educating.

FS: I’ve been thinking about that a lot the past few weeks, coming off of the National Coaches’ Symposium and off of Dr. Stephen Seiler’s talk with NNF last week (which Kapala was partly the brainpower behind). My operable knowledge of physiology as a coach up to now was based on what I learned at an REG camp presentation as a sixteen- or seventeen-year-old kid, and all of a sudden it was like, “whoa, this whole field has evolved a bunch” and I came away with three or four things I was ready to change in my coaching right away . . .

RK: Yeah, and that coaches conference happens what, every two years? Imagine if we made that part of coaching culture. That collaboration and knowledge-sharing: it is imperative. I’ve been paying attention to the system of coaching in international soccer, for example, where American coaches are going over to Germany and realizing just how beneficial the structure and rigor of coaching education is over there.

FS: As in, the accreditation system?

RK: Not so much the accreditation, but more so just how seriously they invest in all the individual aspects of sport development. Like this American soccer coach I was listening to a podcast with [Jesse Marsch, who came up through the German coaching system and now is the first American coach in English Premier League history with Leeds United]. He said he had a year-long course in sports psychology just to get accredited in Germany. We are no year to making that investment in something as beneficial as that.

One of my other initiatives is on that front: I’d like to create a dedicated professional position at Sun Valley who can work with our athletes on sports psychology and wellness. We have always been great at catering to the physical aspects of our athletes, but not the emotional, or just human, aspect of human athletic performance.

FS: Putting the resources to institutionalize new developments in athletic performance seems to be a theme of your work. I ran across an article from our archives where you talk about making training camps, like the U16 camp system, a regular part of the developmental pipeline in the US. That was a decade ago, and now, that’s well-established across US skiing. Is sports psychology and wellness the next front for that you think?

RK: The U16 camp idea was a collaborative idea that came from a couple coaches at REG camp being like, “this is a great system, why aren’t we expanding this type of incentive and experience to kids at the crucial point where they decide to go all in on skiing or not?” And we could do it quickly with relatively few resources. That is the same thing with wellness and catering to that aspect of our athletes. I actually think it is even more important in the American context, too, because we’re correcting for that persistent “toughness” or “suck-it-up” mentality that is a feature in our athletic culture. That has never worked when you look at skiing.

FS: It was interesting that in Johan Olsson’s presentation at the National Coaching Symposium a couple weeks ago, he cited a study on [UCLA’s legendary basketball coach John Wooden] where the main finding was essentially that his main feedback to his players was positive, rather than negative; that was a revelation in the 1970s.

RK: Yeah, and then a couple years after that, [Indiana University basketball coach] Bobby Knight was throwing chairs at his players! Somewhere it got lost, and so we still have to address it in the landscape of our coaching.

FS: Is the answer doing more coach education and dedicating resources to making it part of our clubs?

RK: Yes, I also think it goes to a base-level of empathy. One of the cool things about skiing now versus when I first started coaching is that there is a critical mass of people—coaches or even just parents of athletes—who went through all the highs and lows of ski racing as athletes themselves. We have a depth of knowledge present in skiing that just did not exist in the 1970s and 1980s, and it is so helpful as an athlete to not just have one coach, but a support network, that can help you navigate a really hard, and really rewarding sport. That is special, and we have that going for us.

FS: How do you incorporate that experience into the practice of coaching?

RK: I actually think it is a community thing. Which enough individuals working together is always going to lead to. At the end of the day, that is what we have that is special. I’ve been in this game long enough to see how skiing connections last. Our kids meet other kids from across Intermountain West at JNQs, and they go on to become their friends, neighbors, teammates later in life. It just lasts.

I think about what drives our community to do this sport a lot. There’s certainly not a lot of money in it, and there is not the capital of a lot of Division One college scholarships on offer. I think the ethos of it truly is that the people in cross-country skiing love it deeply. Love it individually, and together.

FS: That’s a beautiful way to say a really true thing. Just to try and collect some of the themes I am seeing run through this, the “Rick Kapala” philosophy towards skiing development seems to include a community powered by that ethos—that love of skiing you talk about—that provides a “complete ecosystem” in terms of the resources needed for athletes to succeed. And you seem to be very careful to say that needs to match the specific context of the place in which the ski community exists.

RK: I think that is fairly well put. The levers we can pull in Sun Valley are different than what those in Minneapolis—or you in Crested Butte—can pull. So you have to be collaborative and observe what works and what doesn’t in the place you are, and then take in knowledge from other places too. That’s how we ultimately make skiing in this country go ’round.

We can’t just do what the Norwegians or Swedes are doing. We have to think about how we do things soundly, but differently. We have been successful in doing that to some extent, but there is always room to improve—which was the most important lesson of my coaching career.

FS: And that’s the most important thing you’re now bringing to development?

RK: For sure.

Ben Theyerl

Ben Theyerl was born into a family now three-generations into nordic ski racing in the US. He grew up skiing for Chippewa Valley Nordic in his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, before spending four years racing for Colby College in Maine. He currently mixes writing and skiing while based out of Crested Butte, CO, where he coaches the best group of high schoolers one could hope to find.