The message from the event organizer was devastating . . . we’d been waiting years to cheer on World Cup skiers in person. Jessie Diggins had worked her magic to get the Sprint Finals onto American soil—and here in Minneapolis no less! But COVID was spreading misery across the globe and our race was cancelled: the Sprint World Cup Finals would not occur. $300 in tickets gone in an email. No swag or alternative compensation ever did arrive. Devastating . . .

As the world recoiled from COVID—as World Cup teams and FIS were making ever-evolving decisions on how best to handle the pandemic—event organizers and citizen racers across the Midwestern US were also scrambling to figure out how to salvage what they could from the 2020-21 winter. Having already registered for multiple loppet events, we were now faced with having to choose between bailing on the events to avoid the COVID risk, or race them in some weird new format. Beyond the normal array of choices regarding classic or freestyle, clothing, food, hydration, and myriad wax options, we now had to decide what “virtual format” to use.

Virtual Racing

The 2021 Vasaloppet in Mora, MN allowed racers to all ski on the same day but used staggered starts with individual timing to avoid congregating in a large crowd. The City of Lakes Loppet in Minneapolis allowed virtual racers to ski on the official course, but scheduled individual start times over multiple days. The American Birkebeiner in Wisconsin was the most liberal with its definition of “virtual racing” and offered wide-ranging options that included skiing at official partner venues around the country, skiing at local non-partnered trails, and even doing other non-ski activities (run, bike, swim, etc.). These all counted as participating in the 2021 virtual Birkie. We signed up for all three of these races and did the Vasaloppet and City of Lakes Loppet in person on the official courses, but completed the virtual Birkie by skiing on our local trails. It was interesting.

While virtual racing seemed like a stop-gap measure to salvage the 2021 season, it got us thinking. The recent explosion in popularity of virtual online racing and the steady rise of e-sports demonstrates how the modern definition of sport and fair competition is changing. The temporary virtual ski solution to the pandemic may become more permanent in light of climate change that is making winters shorter and warmer. In 2015, Vasaloppet USA required competitors to do laps on a frozen lake because there was not enough snow on the trail. In 2017, the American Birkebeiner couldn’t be held due to a lack of snow. As climate change grows worse, FIS has managed to maintain the World Cup season at venues throughout Europe by creating ribbons of artificial snow on fields of brown and green. Premier races in Minnesota and Wisconsin have started making snow too; however, temperature trends suggest that even making artificial snow may be a challenge in the coming years. Will virtual events become standard alternatives to cancellations if we can’t even ski on artificial snow?

Surveys, Questions, and Culture

As cross-country skiers who happen to be anthropologists, we decided to conduct some research. The leadership at the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation recognized the significance of the questions we were asking and agreed to partner with us on the project. They graciously promoted the survey and shared the link with cross-country skiers across North America in order to find out what they thought about virtual racing and a whole lot more. We were also fortunately supported by the Loppet Foundation.

1300 amazing skiers took the time to complete our survey and informed us about:

1) How cross-country skiers define their culture and community, and what this indicates about diversity within our sport;

2) Whether or not people actually like virtual events and if they consider them legitimate forms of racing;

3) How virtual races might impact our sense of culture and community; and,

4) What event organizers can do to maintain and grow our community in light of the negative impacts of climate change on winter. This article is the first in a four-part series that will share the results of what we learned. So what did we learn?

XC Ski Community?

Nearly 100 percent of the people who took the survey feel like they are part of some kind of ski community, but who are these people and who do they include in their group? Do they act like me? Would they buy me a beer at the pub? Almost all of us (97%) include friends and family in our definition of cross-country ski community, and about two-thirds of us also include people who ski at the same places and events that we do. We think of these folks as an “event community.” Just over half of the respondents expanded their community network to include their ski clubs and other organizations, and a full 50% join us by including all free-heel skiers in our broad understanding of Nordic ski community. As academics and master skiers (who would like to become faster skiers!), we were curious to know how we compared to the survey demographics. About two-thirds of the survey participants are between 40 and 69 years old, and surprisingly only 7% are under 29 years old. While the majority self-identify as male or masculine, a third are female or feminine. A fraction of one percent identify as non-binary gender, which is underrepresented in Nordic skiing compared to the US average. More than 9 out of 10 have a college education and over half hold graduate degrees. Almost 40% earn a six-figure salary while only about 14% earn less than $50k, which highlights the perception that cross-country skiing is an expensive sport. As anthropologists, we also wanted to know how cross-country skiers defined their race and ethnicity and 986 respondents typed in a wide range of answers. Fewer than 2% reported a racial description that did not include some form of “white” or “Caucasian.” A total of 7 skiers identified as Hispanic/Latino, 6 as Asian, 3 as African-American, and only 2 as American Indian. These numbers are not representative of the US population percentages and highlight the lack of diversity in our sport, suggesting the need to make our sport more open and accessible to underrepresented groups.

With a basic understanding of who took the survey—and who is included in their ski communities—we then asked how they draw the geographic boundary around their self-perceived community. Based on cell tower locations used by 1188 people to access our online survey, they represent 47 US states, five Canadian provinces, and regions of Norway and England. As Figure 1 shows, the Upper Midwest appears to be the center of the North American cross-country universe! While this is likely a result of the ABSF distributing the survey to their virtual skiers who often look towards Hayward, WI when they draw their maps, as Minnesotans we’re happily biased in seeing the Midwest as skiing Valhalla. Thus, there’s probably a correlation between the need to travel from large urban Midwestern cities to ski the Birkie and the 43% of respondents that defined their community as “regional.” What we didn’t expect was the low proportion of people (8%) who thought of their community on a national scale, compared with those who think internationally (20%). There might be a couple of reasons for this. International coverage of World Cup and Olympic races creates a large-scale perspective for many skiers that naturally subsumes a more restricted national-scale perspective. Additionally, lack of easily accessible video coverage and live commentary of national ski events (e.g., NCAA, US Super Tour) hinders a fan’s ability to engage at a national level.

Community, Culture, and Engagement

With geographic boundaries drawn and scales of community in mind, we then wanted to know if people who call themselves “cross-country skiers” actually ski. It may seem like a funny question, but one never knows. When there’s snow on the ground, the overwhelming majority (82%) of cross-country skiers engage in the sport at least twice a week. While everyone considers themselves a cross-country skier during the winter, 62% of the respondents think this way year round. Do these “year-rounders”, actually practice what they preach? By and large they do. A little over a third ski more than three times per week, and this is what we might expect. What we didn’t expect to find out is that almost 4% of “year-rounders” actually skied less than once per week. Do as they say, not as they do! This is interesting because on the surface it highlights an apparent contradiction between self-identity and behavior. One might expect that those who identify as year-round skiers would ski more than average, not less. But digging a little deeper into our data we see that most of the year-rounders who don’t ski that often are probably training in the off season for those one or two big races during the winter. In terms of engaging in the culture, these folks are as much cross-country skiers as those who log hundreds of kilometers on the snow every winter. How can this be possible?

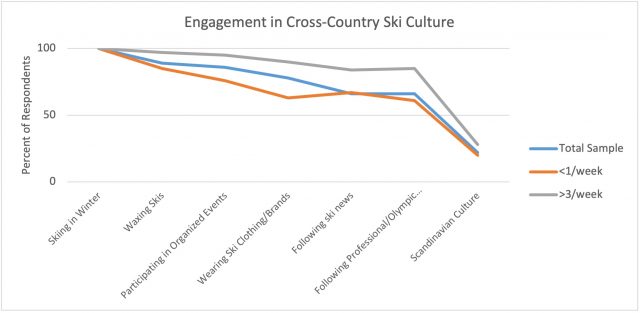

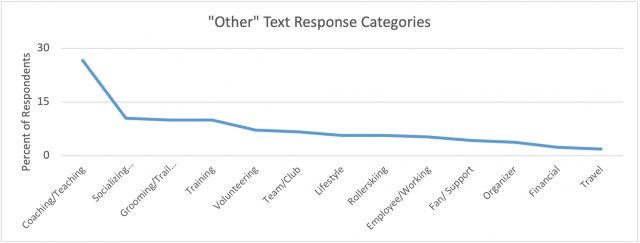

Survey respondents chose between seven different ways in which they engage in cross-country ski culture, and also wrote their own answers. The pattern of responses between the year-rounders who ski all the time and those who hardly ski at all are statistically indistinguishable (Figure 2). And this pattern even holds across the entire sample of 1300. Essentially everyone told us they ski in the winter. Somewhat surprisingly, 89% replied that they also wax their own skis. Think of all those burned finger tips and ruined carpets! What was not a surprise is that participating in organized ski events came in third. Project Runway fans will be happy to know that a full three-quarters of the respondents style out in their favorite ski-brand clothing to signal their cultural membership. Tied for fifth, 66% follow professional races and skiers, and read ski news through online or print media. Almost 200 people typed in other ways they engage in the culture that were not on our list. The most frequent response was coaching/teaching, but socializing with friends and family, grooming/trail maintenance, and training were also common responses (Figure 3). Physical behaviors, material culture, economic investment, active information seeking, and coaching/teaching are all common pathways to engage in cross-country ski culture.

So when does cross-country skiing become part of something larger? To answer this question we go back to the final category of engagement in Figure 2: “As part of Scandinavian culture.” We recognize that the term “Nordic” traditionally includes Finland, in addition to the Scandinavian countries of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and the Faroe Islands (that share an Old Norse language stock). We asked the question about engagement using the term “Scandinavian culture” instead of “Nordic culture” so that survey respondents could think about cross-country skiing as a standalone sport, rather than an embedded cultural act. We hoped to avoid persuading respondents that “Nordic skiing” meant they were automatically participating in “Nordic culture.” A total of 280 respondents (21.5%) told us that they engage in cross-country ski culture as part of a larger engagement with Scandinavian culture.

When people cross-country ski as a way to engage with Scandinavian culture (and more broadly Nordic culture), skiing becomes the journey rather than the destination. The cultural concept of friluftsliv is the perfect example of a life well-lived through regular engagement with nature and using cross-country skiing as a means to that end. The FIS Cross-Country Homologation Manual (FIS 2021) demonstrates how cultural practices and perspectives that historically originated in the Nordic nations are at the heart of our sport. The manual establishes standards and guidelines for ensuring race courses adhere to principles of safe and fair competition, but just as importantly, “to maintain the original ‘soul of the sport’.” In the sections titled “Preserving Cross Country Heritage” and “Environmental Aspects,” the manual references the early history of skiing and societal expectations for the relationship between cross-country skiers and nature. Nordic cultural heritage is thoroughly embedded in the ideals, iconography, and language used to describe our sport.

Many North American skiers attend iconic events with cultural and symbolic associations focused on the Viking image (e.g., American Birkebeiner, Vasaloppet USA, SISU Ski Fest, City of Lakes Loppet), and this is especially evident in Minnesota (Figure 4). For those whose immigrant family histories include Nordic ancestors, cross-country skiing may indeed be part of their cultural heritage. But for many others, it is not. Regarding ethnicity, only 46 of the survey respondents (3.5%) clearly identified as Scandinavian. Many respondents described their ethnicity as “European” or “northern European” that might include Scandinavian countries so this result is considered a minimum. Of these 46 respondents, 74% indicated they cross-country ski “as part of Scandinavian culture.” This strong correlation is expected given the important role of skiing in Nordic countries and reinforces the direct association captured in the very name of the sport. Just as importantly, a quarter of these respondents didn’t see a necessary connection between Scandinavian ethnicity and the act of cross-country skiing. Of particular interest, some folks identified their ethnicity as not Scandinavian (e.g., Taiwanese, Asian-Pacific Islander, Czechoslovakian, Lithuanian, German, Dutch, Polish, Swiss, Scottish), while also indicating that they ski as a way to engage with Scandinavian culture. This demonstrates how people can use sport to intentionally cross cultural boundaries.

The relationship between race, ethnicity, and cross-country skiing is complex. While ethnic Scandinavians strongly associate cross-country skiing with their culture, so too will other folks who are not Scandinavian. Notably, more than three-quarters of the respondents (regardless of racial identity) didn’t emphasize a connection with Scandinavian culture at all. In North America, we may want to give some careful consideration to the ways in which we promote the sport to new members. Modern Viking iconography and associated cultural ideals may appeal to some cross-country skiers and event organizers because of a shared cultural background. Events that have built part of their public image on Scandinavian heritage do not necessarily need to change; however, promoting other positive aspects such as a healthy lifestyle, getting outside in winter, and building a bond with nature may appeal to a wider audience and could be important factors for promoting diversity and growth of the sport for everyone. The fun and excitement of competitive endurance racing is another big attractor for many people, and we will address the impacts of changing climate and virtual formats on this in subsequent articles.

We have learned that there are definite cross-country ski communities, and that skiers engage in the culture in very recognizable ways. In general, we mostly like to ski a couple of times a week with friends and family, and regularly attend organized ski events at a regional scale. We’re gearheads who enjoy geeking out on wax and ski technology, and we communicate our love for the culture through the clothes we wear. We’re also apparently older, well-educated, cis-gendered white people, but these demographics may be biased towards folks who skied the American Birkebeiner. Even if biased, this sample of skiers is very relevant to this research because they have an important contribution to make when examining the potential impacts of virtual ski events. Cultures evolve and adapt. Climate change is forcing the Nordic ski community to deal with warmer and shorter winters. What happens to our culture and community if virtual racing becomes part of our adaptation to the near-term future? We explore this question next by looking at the pros and cons of virtual racing through the eyes of those who lived through it.

Mark P. Muñiz, PhD is a Minnesota transplant who grew up in Florida, but enjoys a cold snowy winter over a hot humid summer any time. His cross-country ski adventures have included loppet races and volunteer coaching for the Minnesota Youth Ski League. In the warm season he loves cycling and is still a little wary of jumping on rollerskis. He currently teaches as a Professor in the Dept. of Anthropology at St. Cloud State University, MN.

Matthew A. Tornow, PhD is a Professor of Anthropology at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota. His research interests focus on primate adaptation and behavior, including that of humans. As a native of central Illinois, he spent much of his youth and early adulthood driving north to seek out the snow. Now he spends his winters skiing the local trails and doing a little racing. When there’s no snow on the ground, you can find Matt running through the woods somewhere.