Parallax is an effect where the objects in the background of an image appear to move more slowly than the objects in the foreground. In animation, it’s traditionally been used to add depth to an otherwise two-dimensional world. With the background moving slowly, the faster movement in the foreground implies that time is moving. In effect, parallax is a way of adding time into one’s understanding of a place.

I reckon that the essential experience of being in the mountains is based in parallax. The mountains are the only environment where if you only ever experienced them, you would have a complete understanding of where humans are set in the universe. Ancient fissures in the Earth stretch the scales of time beyond you, and when put up right against them, you get a sense that we’re all in a small moment in an infinitesimal smaller place in time. When you attune yourself to parallax, you attune yourself to time not as an instant, but as a fluid, playful thing.

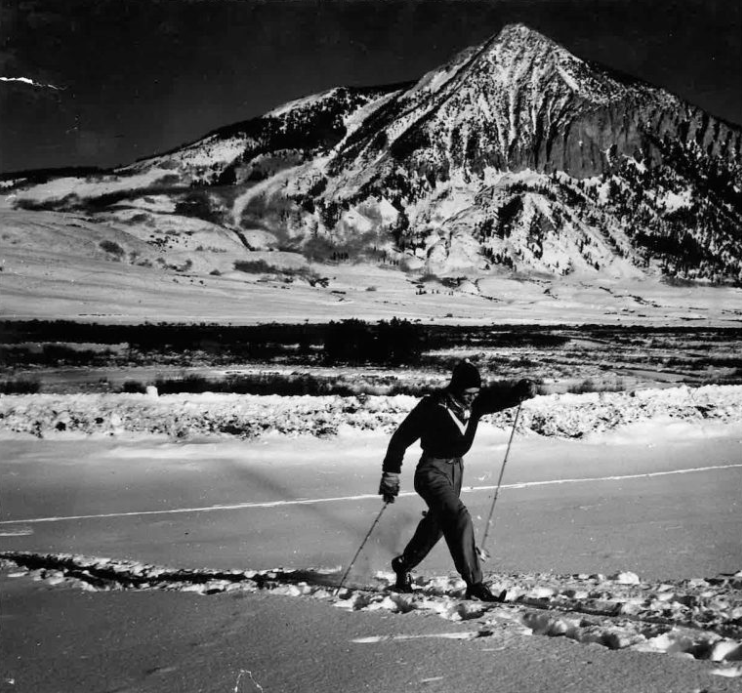

I’ve been especially experiencing a parallax effect lately while looking at old pictures of the mountain town of Crested Butte, Colorado. Crested Butte is set in the platonic ideal of a parallax setting, wholly occupying the lowest point of a glacial valley 9,000 feet up in the central Rocky Mountains. It’s also neatly framed by Mt. Crested Butte, a 12,168 ft laccolith just East of the valley, which is Seussian in its whimsical, perfect jaggedness. In the foreground of that mountain, all the great tropes of western history have been captured. There’s volumes of old sepia photographs with people, looking out from bonnets and stetsons, all distinctly of a time. In the background though, that perfectly pointed mountain. The creases on its sides are the same as the vivid shadows you see when you walk outside your front door today. Always there, always looming. The sensation at the heart of viewing photographs like this is at once humbling and connective. The first thought is that you’re among the essential history of a place that has always been transitory, where everyone is always just passing through. The other is that between you and the Utes and the miners, there is the essential experience of a moment in time where you learn that lesson looking up at that rocky old mountain.

All of which has got me thinking about another photograph. My stint in the long chorus of Crested Butte has been as a ski coach and a writer. As such, the last couple of years have allowed me to fully indulge a pet interest in ski history. And in that capacity, there’s a photograph that keeps finding its way to my eyes, both literal and in my mind.

Here. There’s a group of men, stetson’s affixed, looking out and postured. Too long skis, and too long wooden poles accompany them, which produces a kind of defiant effect. They share the kind of pose every skier takes on to this day about to head out onto the trail. A nod that skiing is an unnatural way to get around a frozen world, but that we’ve figured out the trick, and it’s made weathering the winter a lot more fun.

Through some serendipity, I’ve learned a lot about the men in this photo over the past few years. It was taken in the early 1880s and is often denoted as the first ski club on record in United States history, formed at the gold mining boom camp of Irwin, Colorado, five miles West of present-day Crested Butte and sitting at 10,500ft, during its haughty gold rush days. In most sources, there’s a quick addendum to point out that it was actually the “Irwin snowshoe club,: which was the contemporary description for skiing, and that the single wooden pole each man carries was representative of how the sport was practiced then.

The most in-depth sources also identify the front and center man as Al Johnson. In the history of Crested Butte, Johnson holds a kind of Paul Bunyan status among the ski bums. By which I mean he’s a much-lauded folk character (with his own folk song) intentionally stretched in the proportion of his size and abilities to represent an ideal of what being committed to a life centered around skiing looked like in a semi-imagined past. He took whatever work could get him out on skis, which, in the 19th century, was carrying mail to all the mining camps in the Elk Mountains. He was always up for a race. And he was a devout Telemarker – heel free, mind free – before a term even existed. Arch-coolness. For it, he got a Telemark race now in its fiftieth year named after him (and won frequently by FasterSkier fan Pat O’Neil, shoutout).

All of which color the black and white photo, but don’t necessarily change your initial impressions. In nearly all settings it’s displayed, this is a photo meant to temper the impression that this is where North American skiing came from. And likewise, alongside images of lycra-clad US Ski Team suits, carbon poles and skinny skis, it points to where skiing went from Irwin. The parallax does its job. The background is all old, black and white, and here we are today, with skiing in vivid color.

The other impact of parallax though, is to imbue connectedness. And so, I’ve been thinking about ol’ Al Johnson a whole lot lately as the winter melted away in the high country, retreating from the valley floor in Crested Butte up to where it never seems to go away, twelve miles west on Kebler Pass in the isolated pocket of alpine meadows where the Irwin snowshoe club used to ply its trade. Here, in a couple of wetlands and along some alpine lake shorelines there’s still skiing well into June, and along with an eager group of Crested Butte’s best up and comers, skiing towards a common recognition that the old show-shoers and we do today – it’s always a wonder to ski, and by some miracle, a sublime experience to never have to leave it as the winter retreats. When through time and circumstance you find yourself in Irwin, you can’t help but ski. It was true for the miners, and it’s true for me today.

The bare facts of why are up to immutable geography, one-part outsized precipitation, and one-part thermal inclination. Creste Butte sits at 9,000 feet, gathering an average of 236 inches of snow per year. Go up 1,500 feet though, and the snowfall grows exponentially. The remnants of Irwin collect closer to an average of 600 inches of snow each winter. The evidence for why most residents of Irwin packed up the town and quite literally dragged their buildings down to Crested Butte lies right there. The inordinate amounts of snow get a prolonged life too due to the Gunnison River Valley’s central place in Colorado, making it one of the most prone places in the state to cold air pooling (this process is why Gunnison, elevation 7,000ft, is colder during the dead of winter than Crested Butte, elevation, 9,000 feet) the effect happens to some effect up in the smaller valley that the old Irwin mining camp existed in, elevation 10,500 feet, collecting the supercold air off of the 12,000-13,000ft Ruby Range that towers above the valley.

To understand the results of Irwin’s positioning just-so in the universe though, is best left on cosmic terms. When I first found the relatively flat patches of sun-cupped snow ready not just for metal-edged backcountry set-ups, but for skinny skis, in my first spring in Crested Butte, I felt as if I’d stumbled upon some epiphanic geography. A born Midwesterner, skiing was the province of a specific slice of the year, which only heightened all the appreciation that it brought you. To ski was to turn the evolutionary perception of winter on its head. Suddenly the cold was welcome. Likewise, it connected you in a very specific way to very specific people. There are still folks I’ve known my entire life in my hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin, good folks, that I hardly recognize without a buff and a beanie on their head, and there’s a hinted appeal of sociality that comes exclusively with the seasons. The whispers I did get that snow could exist past March were comprehensible. Bend, Oregon and California lied along continental meeting points where the moisture of an ocean was due to meet with the mountains. When I came across Irwin though, it felt as if I was let in on a secret. Just up the road, literally, there was a place where some complex set of factors had conspired to mean that the winter, skiing, and what skiing brought in the way of metaphysical relief never seemed to go away. Since then, every ski in May or June has glowed with a little more sentimentality, and letting others in on the secret has stretched the poignant feeling of joy incurred by sharing a great ski with others well into the year.

In short, it’s been a dream. One that I know that’s happened by that quintessential rule of the mountains, by parallax. Up at Irwin, time’s been loosed from the sockets that bolt us together. The winter is there in the summer. At the precipice of its cliffs looking South over the Gunnison country, you can literally see all seasons as once. Green stretches over the horizon, with snow under your feet. For their part, the kids growing up on skis in Crested Butte have started to fully embrace, and appreciate, the singular experience they get out of their backyard. A recent report from one of their skis was that they’d found an abandoned canoe on the shores of one of the isolated alpine lakes accessible easily only in the winter, and decided to try and makeshift a combination workout by taking to a still melting out lake.

This spring, the quintessential Irwin summer ski for myself happened over Memorial Day weekend. A cadre of Crested Buttians and I headed up the little road west of town early, before the sun that had started to bring summer to the Rockies bore down in full force. Our ages stretched literally from 8 to (nearly) 80. There was the full Larson family, with Mom and Dad Drew and Noelle accompanied by Benaiah (13), Gabe (11), and Simi (8), our lead middle school Devo Team Coach Murray Banks, and a couple of his Assistants, alumni of Crested Butte Nordic Team, the O’Neil twins, Katie and Piper. Our objective was to split off into two groups. The O’Neil girls and myself set out with Benaiah and Gabe to see if we could make it to one of the stunning overlooks that follow a ridge East-to-West, and from which on a clear day the San Juan Mountains loom large across the whole of the Gunnison country. Murray and Simi, oldest and youngest in the group, meanwhile, were set to make the “fun for ages 8 to 80” moniker a literal thing for skiing on the valley floor. A couple hours of stumbles, breaks through the crust, moments where you would swear the skiing was as good as mid-winter, and a lot of views, and we were satisfied. Not just with the that ski, but with what the ski represented. Up there, where the winter never ends, we could see that the connective tissue it brings between those that practice the sport all winter long don’t have too either. Between that group, there had been a lot of kilometers skiing in a lot of places. For an instance, we skied a few more. And with the mountains there as a backdrop, full parallax in effect, the bounds of time between us, stretching back to all of those that had come to Irwin, and Crested Butte, and found that same joy in skiing, looked ready to enter a timeline more akin to those that govern the mountains. Timeless, sublime, glowing with a towering beauty too.

Ben Theyerl

Ben Theyerl was born into a family now three-generations into nordic ski racing in the US. He grew up skiing for Chippewa Valley Nordic in his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, before spending four years racing for Colby College in Maine. He currently mixes writing and skiing while based out of Crested Butte, CO, where he coaches the best group of high schoolers one could hope to find.