“Play True” is the World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) outward appeal to athletes, coaches, doctors, a myriad of handlers and advisers, and, ironically, anti-doping labs to keep sport clean.

On one hand, “Play True” could be interpreted as a baseline demand, something educators might instill in elementary students. But it also reads like a plea; for fans of the sport and most importantly participant athletes themselves, there’s a lot to lose when athletes “Play False”.

The sharpened teeth behind words like “Play True” are the tests administered to detect doping and potential bans for positive tests, although WADA’s anti-doping arsenal also includes a confidential digital hotline for individuals to file claims of suspected doping.

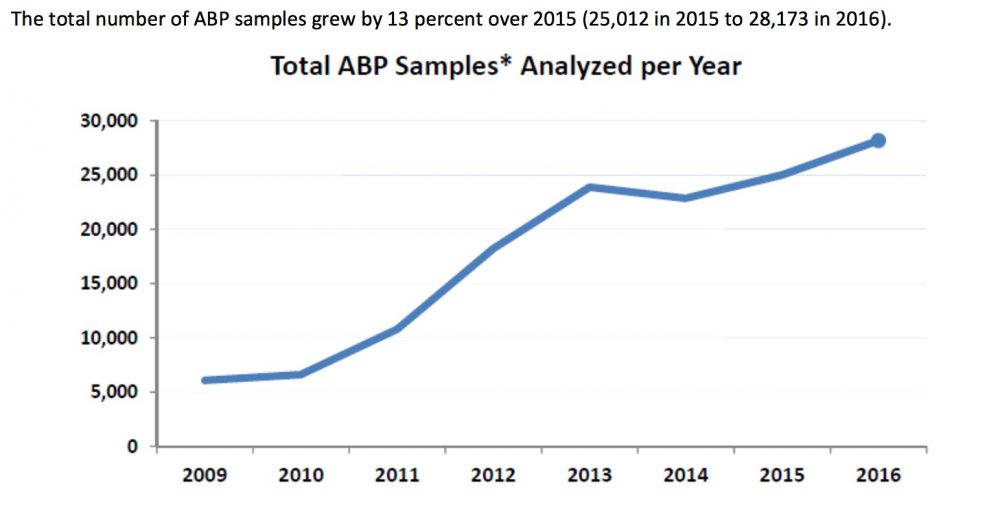

On Oct. 25, WADA released its annual testing numbers in a massive document titled “2016 Anti-Doping Testing Figures.” The report itemizes every sample tested by the 34 WADA-accredited labs in 2016 and uploaded into WADA’s Anti-Doping Administration and Management System (ADAMS). The information includes all in- and out-of-competition tests on both athlete urine and blood, and results for Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) blood analysis.

The 2016 report does not include data or discussion of Anti-Doping Rule Violations (ADRVs). A discussion of 2016 ADRVs is expected sometime in 2018. The report does include the number of Adverse Analytical Findings (AAF) and Atypical Findings (ATF).

Here’s the simple appetizer before the full course: an AAF occurs when a sample contains a prohibited substance. An ATF, according to WADA, indicates that “while there may not be an adverse analytical finding, there may be some suspicion according to the results and that further analysis or investigation should be conducted.” After an ATF is investigated, it could lead to a negative result (the suspicion was not warranted), an AAF (something was found), or it may be canceled.

WADA stresses that in reading and interpreting 2016 Anti-Doping testing Figures report, “one single result does not necessarily correspond to one athlete. Results may correspond to multiple findings regarding the same athlete or measurements performed on the same athlete; such as, in the case of longitudinal studies of testosterone.”

Also, the number of AAFs in the 2016 testing report will not correlate directly to the number of ADRVs in 2016. Among other reasons, that is because some AAFs end up being explained by the athlete having a Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE).

The Report’s Findings

Samples Analyzed and Reported by Accredited Laboratories in ADAMS)

It’s worth mentioning again the length and comprehensiveness of this report. FasterSkier created a Google spreadsheet to better understand testing results in three sports we cover: biathlon, cross-country skiing and nordic combined. This process simply allowed FasterSkier to compare testing analysis in these sports more efficiently, and you can see the spreadsheet yourself at the link above.

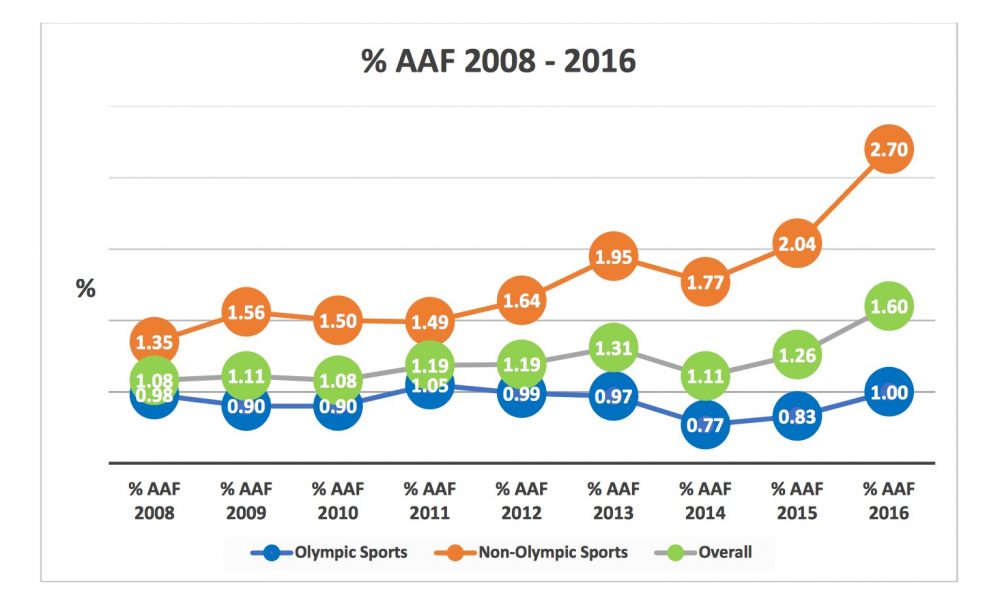

WADA articulated what it felt were the report’s highlights. The anti-doping watchdog advertised what it called a “noteworthy” development: that the total number of AAFs increased from 1.2 percent in 2015 to 1.6 percent in 2016. WADA also qualifies the total increase in positive tests as “partly related” to AAFs attributed to Meldonium — that drug was placed on the prohibited list in January 2016 without much consideration of how long it might stay in athletes’ bodies, or whether athletes had enough advance warning to stop taking the drug.

At the same time, WADA noted that the total number of samples tested decreased from 303,369 to 300,565 from 2015 to 2016. WADA claimed that despite the downturn in the total number of tests, the administration and efficacy of its tests contributed to the higher AAFs total in 2016 compared to 2015.

Totals

Starting with biathlon, there were 1688 total samples tested: 671 were in-competition urine samples, 39 in-competition blood samples, 859 out-of-competition urine samples, and 119 out-of-competition blood samples. Of those 1688 samples, 16, or 0.9 percent of the total, were considered AAFs (seven in-competition AAFs and nine out-of-competition AAFs, all from urine samples).

Terms and Abbreviations

(as referenced in FS spreadsheet)

IC: In‐Competition

OOC: Out‐of‐Competition

Sample: Any biological material collected for the purposes of Doping Control* Adverse Analytical Finding

AAF: Adverse Analytical Finding

ARF: Atypical Finding

GC/C/IRMS: Gas Chromatograph/Carbon/Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry (e.g.”IRMS”)

ESA: Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agent**

hGH Isoforms: Human Growth Hormone Isoform Differential Immunoassay

hGH Biomarkers: Human Growth Hormone Biomarkers

GHRF (GHS/GHRP): Growth Hormone Releasing Factors (Growth Hormone Secretagogues/GH‐Releasing Peptides)

GHRF (GHRH): Growth Hormone Releasing Factors (Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone)

GnRH: Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormones

HBT: Homologous Blood Transfusion

HBOC: Haemaglobin Based Oxygen Carrier

IGF-I: Insulin‐like Growth Factor‐I (and its analogs) Athlete Biological Passport

ABP: Athlete Biological Passport

IOC: International Olympic Committee

AIOWF: Association of International Olympic Winter Sports Federations

ASOIF: Association of Summer Olympic International Sports Federations

ADAMS: Anti‐Doping Administration and Management System

TUE: Therapeutic Use Exemption

Cross-country skiing accounted for 2135 total samples tested. 623 were in-competition urine tests, while 19 were in-competition blood tests. 1163 were out-of-competition urine tests, 330 out-of-competition blood tests. The sport had a single in-competition AAF and eight out-of-competition AAFs — again, all derived from urine samples. Out of all the cross-country samples tested, 0.4 percent were AAFs.

Nordic combined had 393 total tests. Eighty-eight of those were in-competition urine tests, six were in-competition blood tests. According to the WADA report, out-of-competition urine tests accounted for the majority of samples taken; 245 urine samples were analyzed and 54 out-of-competition blood tests were recorded. Nordic combined had two confirmed AAFs — both from in-competition urine tests. Of all the nordic-combined tests, 0.5 percent were AAFs.

How exactly should we read these tea leaves? It has been well-documented in the mainstream media, as well as in documentaries like Icarus, that historically, the anti-doping system can be gamed. Methods other than drug testing have shown that between 15 and 40 percent of elite athletes have intentionally doped at some point. With the low rate of AAFs in the three sports highlighted by FasterSkier, biathlon, cross-country and nordic combined, a few basic conclusions can be made.

With the low rate of AAFs in the three sports highlighted by FasterSkier, biathlon, cross-country and nordic combined, a few basic conclusions can be made: the possibility of doping and skiing undetected remains, but if the “Play Fair” mantra works, the majority of athletes are training and racing clean.

Tests for Blood Doping

Of importance to policing endurance sports like biathlon, cross-country and nordic combined is increased implementation of WADA’s Technical Document for Sport Specific Analysis (TDSSA). The TDSSA demands that certain sports conduct a mandatory minimum of tests to screen for specific drugs.

For both biathlon and cross-country, the TDSSA calls for enhanced testing for Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agents (ESAs) — think EPO. There’s also a required testing minimum for Growth Hormone (GH) and Growth Hormone Releasing Factors (GHRFs). As of January 2017, the current TDSSA calls for 60 percent of all samples in biathlon and cross-country to be tested for ESAs and 10 percent for GH and GHRF’s respectively.

Partly because of this, the 2016 WADA Anti-Doping Testing Figures report also includes data about specific tests conducted on urine and blood samples – like the ESA or GH tests.

ESAs stimulate red blood cell production in the body. Several ESAs are available, the one most closely followed in endurance sport being recombinant erythropoietin (EPO). Both anecdotally and in research, EPO has been shown to boost endurance, power thresholds and recovery. When it comes to those willing to cheat in endurance sport, ESAs are a go-to. They appear to work.

As a result, WADA has emphasized the testing of both urine and blood for ESAs in sports where an ESA would benefit. It follows that the majority of total samples tested in biathlon and cross-country are comprised of ESA tests. (ESA testing in nordic combined did not constitute a majority of the specific tests administered.)

ESA testing accounted for nearly 63 percent of all the tests in biathlon. In biathlon, 469 in-competition urine tests and 592 out-of-competition urine tests for ESAs were administered with no AAFs. The number of in- and out-of-competition blood tests for ESAs were far less. There were 29 in-competition ESA blood tests and 17 out-of-competition blood tests. Again, not a single sample flagged an AAF.

For cross-country, 1107 samples were tested for ESAs — comprising almost 52 percent of the total 2135 cross-country samples tested in 2016. Like biathlon, nearly all of these samples were from urine samples. 316 tests were from in-competition urine tests and 735 from out-of-competition urine tests. Eight in-competition blood tests and four out-of-competition blood tests were screened for ESAs in cross-country. No AAFs for ESAs were documented in cross-country.

Like biathlon and cross-country, nordic combined was void of any AAFs in their ESA testing pool. Thirty-two in-competition urine and 106 out of competition urine ESA tests occurred in nordic combined. No in-competition blood tests and one out of competition blood test for ESAs were administered. ESA testing made up 35 percent of the total test in nordic combined.

Prohibited Substances Used in Nordic Sport

Reflecting back on the total number of AAFs reported in biathlon, cross-country and nordic combined (16, 9 and 2, respectively), WADA did, however, provide information on the drug class of those AAFs.

In biathlon, 14 of those AAFs were flagged in the Hormone and Metabolic Modulators drug class, whereas two were in the Diuretics and Other Masking Agents drug class. That’s maybe not surprising as meldonium is a metabolic modulator, and there was a burst of findings of meldonium in early 2016, with Ukrainian biathlete Olga Abramova as just one example. Several of the athletes were ultimately cleared without sanctions.

For cross-country, there was one AAF in the Anabolic Agents drug class, two in the Beta-2 Agonist drug class (which includes asthma medications), five in the Hormone and Metabolic Modulators drug class, one in the Stimulants drug class, and one in the Glucocortico-steroids drug class were noted.

In nordic combined, the two AAFs were both in the Stimulants drug class.

Athlete Biological Passport (ABP)

In recent years, ABPs have been established throughout the sporting world. Rather than a method to catch an athlete at a particular competition or out of competition training block, ABPs are more longitudinal in nature. WADA is upfront about the intended function of ABPs. The fundamental principle of the Athlete Biological Passport (ABP) is to generate a baseline of data for specific biological markers in an athlete. For example, each athlete’s testosterone and hematocrit levels are tracked over time. When an ABP test is taken, the purpose is to determine if any of the biological markers sampled are elevated or inconsistent – a big red flag – compared to that baseline.

WADA also clarifies that anti-doping organizations can pursue an ADRV simply based on an atypical ABP. No adverse analytical finding is needed to pursue a doping violation when an ABP is suspect.

In biathlon, 960 total ABP samples were analyzed: eight in-competition and 952 out-of-competition. The testing authority responsible for testing 645 of those out-of-competition samples was the International Biathlon Union (IBU).

Cross-country accounted for 883 total ABP samples; 88 in-competition and 795 out-of-competition.

Nordic combined amassed 224 total ABP samples; 21 in-competition and 203 out-of-competition.

Conclusions and Opinions

Stating the obvious, the anti-doping crusade evolves. The 2016 testing report’s substance lies in its depth and breadth. Although no athlete names are publicly associated with specific ATFs and AAFs in the report, a better understanding of how WADA and the global “Signatories to the [WADA] Code,” are advancing clean sport can be gleaned.

Broadly speaking, the report’s findings indicate that the testing of athletes’ blood may be a misuse of resources.

An article at the Sports Integrity Initiative titled “WADA 2016 Test Figures P1: Blood tests are not catching dopers” reveals a key pattern in the report. The article’s author, journalist Andy Brown, calls attention to the following: when considering all summer and winter Olympic sports together, 3,200 in-competition blood tests were run, but only 17 AAFs resulted. Out-of-competition testing was far more routine, with 12,443 blood tests run. Under that massive testing net, only 11 AAFs were returned.

Disaggregating the AAF return on blood tests in the winter Olympic Sports may raise more questions than it answers. The 197 total in-competition blood tests performed in the winter Olympic disciplines amassed no AAFs. There were no AAFs for the 1,104 out-of-competition blood tests on the winter side, either. Blood testing is more costly, and data indicates it may not have its desired effect as a doping deterrent.

Jason Albert

Jason lives in Bend, Ore., and can often be seen chasing his two boys around town. He’s a self-proclaimed audio geek. That all started back in the early 1990s when he convinced a naive public radio editor he should report a story from Alaska’s, Ruth Gorge. Now, Jason’s common companion is his field-recording gear.