All ski boots come with insoles. None of them are any good. Some might be fair—maybe even usable for those with strong feet, neutral biomechanics, and impeccable technique—but, for most of us, they’re garbage. Literally. Throw them away and get some good insoles.

Why Do I Need a Good Insole?

Balance

Quite simplified, balance is a product of the nervous system. Our eyes, inner ears, muscles, tendons, joints, and skin are constantly sending information through the nervous system so the body can monitor, regulate, and coordinate movements. Proprioception is the fancy term for the body’s awareness of its position in space. Try this: close your eyes and try to touch your nose with your right index finger and then your left index finger. You should have been able to do this easily without poking yourself in the eye. This is because the nerve receptors throughout your arm are part of the feedback loop that guides the muscle contractions responsible for movement.

When standing on one leg (or one ski), our ability to maintain balance is aided by sensory information from the bottom of the foot. Receptors in the skin tell the nervous system how we are standing—if pressure is predominantly through the ball of the foot or the heel, the inside of the foot or the outside. A good insole will enhance this feedback loop by providing sensory information and tactile cues to the nervous system.

Stability

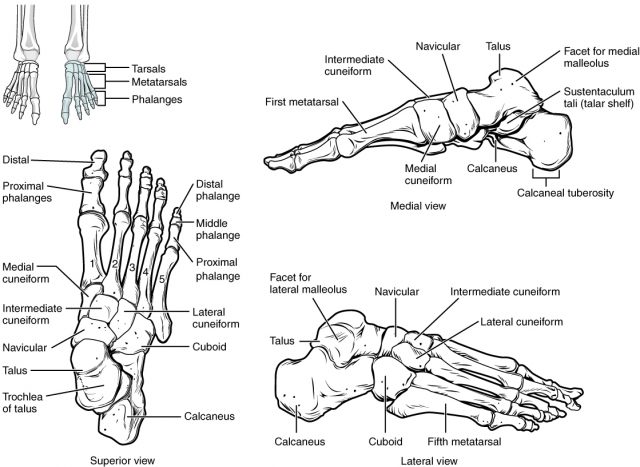

Your foot has 26 bones, 19 muscles (plus another 10 that are technically in the lower leg but act on the foot), and 33 joints, all of which are your body’s connection between legs and skis. The job of the ski boot is to enhance the connection between leg and ski. Boot technology—and, thankfully, color schemes—have improved significantly since the dawn of skate skiing in the ‘80s. Modern skate boots use rigid plastic or carbon fiber in the soles and ankle cuffs to offer external support and decrease the demand on the muscles and joints.

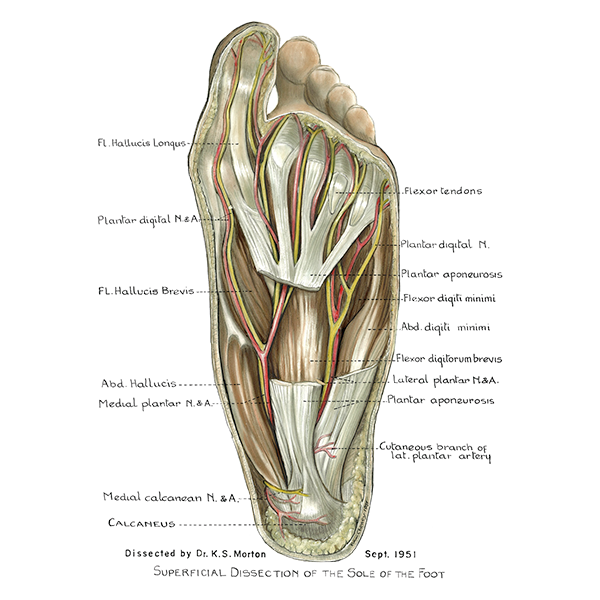

A good insole will also decrease the workload. With skating technique, the joints of our feet should be held relatively still throughout the cycle of weighting the glide ski, pushing off, and swinging back to glide. We want those joints held in place with as little effort as possible. A good insole, comprised of materials that do not collapse under body weight, will support the foot through the calcaneus, tarsal, and metatarsal bones, making it easier for the muscles of the foot to maintain stability. A foot that collapses or changes shape significantly (this is most obvious in foot that has a high arch when held off the floor but a very low arch when standing) is inefficient, increases muscle demand, and likely bleeds power.

Additionally, we want the talocrural (ankle) joint to function in a neutral position. A foot that changes shape significantly is liable to affect the ankle joint in the process. When the inside of the foot drops to the floor, it often takes the ankle joint and thus the tibia (shin bone) with it into internal rotation. Remember that the shin bone is connected to the knee bone and the knee bone is connected to hip bone. By supporting the foot and limiting changes in shape, we can minimize the sequelae of adverse effects up the leg: tibial internal rotation, knee valgus, hip adduction and internal rotation. (If the changes in foot shape are considerable, it may be that a good insole isn’t good enough and a custom orthotic may be better. More on that below.)

What’s a Good Insole?

A try-before-you-buy approach is highly recommended. Perhaps your ski shop, but definitely your local outdoor or running store will have several different insoles to try. And you should try them all… except the squishy ones. We’re looking for support not shock absorption. Desirable insole material should be fairly firm and hold its shape. Rigid plastic pieces are generally ok–remember that your foot is not articulating inside the skate boots. Also, consider the thickness of the insole–best to try them on with your boots to make sure they don’t take up too much volume.

Sizing is more about where the arch hits your foot vs the length of the insole (which can always be trimmed to fit). It’s not uncommon to go up a size or two from what the box recommends.

The insole is there to support your foot, not push it around. The arch of the insole should fill the space between your foot and the floor. Too much from the insole and your foot is going to be pushed onto the outside. Not enough from the insole and you’ve wasted your money. It should be the way Goldilocks wanted it: just right.

Since the whole idea here is for the insole to facilitate balance, stability, and control of the ankle joint, you need to test the insoles: balance on one leg both barefoot and on each of the insole candidates. Repeat the process with a small single leg squat (i.e., go into hip/knee/ankle flexion like glide ski position). The insole should make these tests easier. If it’s more challenging or less stable while standing on the insole, then it’s likely to make your skiing worse. Ultimately, a good insole is one that makes balancing and squatting easier to control.

Additional Comments:

Custom orthotics come in two general categories. One is simply an insole that is custom molded to your foot. This ensures that the insole follows the contours of your foot and fills the arch appropriately. The other is custom molded but includes additional, strategically located material for greater external support of the foot. These can get quite expensive so they’re not typically the first thing to try. However, if you have foot, ankle, or knee pain with skiing, and have already tried some aftermarket insoles, custom orthotics may be very beneficial. I’d refer you to your friendly, neighborhood physical therapist for guidance.

Classic vs skate. As mentioned previously, the joints in the feet have minimal articulation while skating, but we most definitely move through our metatarsophalangeal joints (ball of the foot) with classic. The same general guidance on insoles still holds; however, I’d stay away from overly stiff materials (the insole should flex very easily where your toes would bend). Custom orthotics might also be different between skate and classic where the external material for the skate orthotic might be too obtrusive with the joint articulation in classic boots. The orthotic approach for classic boots will be more like that used in running shoes where there needs to be articulation of the foot joints but we’re looking to support, not block, that motion. In skate boots (also in cycling shoes and alpine boots), we really do want to block the foot motion.

Ned Dowling

Ned lives in Salt Lake City, UT where his motto has become, “Came for the powder skiing, stayed for the Nordic.” He is a Physical Therapist at the University of Utah and a member of the US Ski Team medical pool. He can be contacted at ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.