A tale of how I skied faster than Kikkan Randall for exactly five minutes and 39 seconds until I got tired and she hit more rifle targets than I did.

Once upon a time, I was a serious, though definitively not successful, cross-country skier. I raced for my college team in Maine, then kept at it afterward and one time finished 17th (I think, I can’t find the results any more) at the Tour of Anchorage, which is just good enough to sound kind of impressive to folks who don’t know much about cross-country skiing and also quite clearly unimpressive enough as a high water mark for my career that it doesn’t feel too immodest to share.

Then, I developed a heart arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, that seemed to be associated with intense and extensive exercise, so in 2018, I quit racing and intense interval training, started reading more books and generally began living a more balanced life. (If anyone wants to talk about how developing a serious-if-not-life-threatening medical condition can actually be life-changing in positive, not just negative ways, I am here for it.)

Anyway, I still try to exercise every day, but I don’t really compete any more. Except when something reallllllllly enticing comes along, like an email I got this week from Rachel Steer.

Rachel, if you don’t know her, is one of those Professional Anchorage People Who Just So Happened To Also Compete At The Olympics Back In The Day. (Seriously, you can’t walk into an engineering firm here without tripping over them.)

Rachel was once an international caliber biathlete, racing at two different Olympics, in 2002 and 2006. Today, we’re both members of a little group that meets on a weekly basis for interval training — I don’t really go any more, I just read the planning emails — and on Wednesday, she sent out a message about a “low-key local biathlon race” on Sunday.

“I’ve convinced Kikkan to do it with me,” Rachel said. “I know there’s a few of you on this list who are former biathletes (or who would like to give it a try). THIS IS YOUR CHANCE!”

If you live under a rock, or outside of Alaska, “Kikkan” is Kikkan Randall, another one of those PAPWJSHTACATOBITDs (Professional Anchorage People Who Just So Happened To Also Compete At The Olympics Back In The Day). She also owns a gold medal from the 2018 games in South Korea.

The idea of jumping into a race with Rachel and Kikkan, involving skis and guns, even though I hadn’t trained for it, sounded pretty fun. So I said yes.

A quick primer on biathlon: It alternates laps of a cross-country ski course with shooting at targets, 50 meters away, with .22 rifles. Missing a target, depending on the specific race format, puts you at a disadvantage by either adding a minute to your overall time, or requiring you to ski a short extra “penalty lap” that’s tacked on to the regular course. The beauty of the sport is its balance between fast and slow — the speed and brute force of racing paired with the stillness and fine motor skills of shooting. Think running a mile as fast as you can, then trying to thread a needle.

The sport, of course, has its roots in Scandinavia, “where early inhabitants revered the Norse god Ull as both the ski god and the hunting god,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Ull’s goddess wife, Skadi, “was also celebrated as a hunter-skier” — making her, apparently, the first in a long line of badass female biathletes — and the “combined skills of skiing and marksmanship were first developed by the region’s militaries,” Britannica says. The first recorded competition was in 1767.

TL;DR, it’s Viking shit. Except the sport has evolved: Athletes now race with carbon fiber rifles on their backs, star in Swedish reality television series and perform in front of thousands of (often drunk) spectators and for millions of European fans watching on TV.

What’s not to like?

So, on Sunday morning, I woke up, pulled out my college racing spandex and drove to Kincaid Park, where I met up with Rachel, Kikkan and a handful of other adults for a rifle safety training with a bevy of friendly, energetic volunteers from the Anchorage Biathlon Club.

One of the first questions I got, when I arrived: Have you ever done this before? Once, I said, when I was just out of college. No one was wounded, I quipped, which prompted pained smiles from the safety training leaders that actually upon reflection were probably grimaces.

Biathletes take safety seriously. You can’t shoot until a safety officer opens the range, and there were three obvious safety principles (if I remember them correctly): Don’t point the rifle anywhere except straight up or downrange; don’t load the magazine (a sort of packet of five bullets) into the gun until you’re ready to start shooting; and don’t put your finger on the trigger until you’re pointing your gun at the targets.

There were only a few people at the race without our own rifles, so the organizers were able to give each of us a loaner. After 10 practice shots and a few warmup laps, I lined up for the race as the last of 30 competitors, who would start one at a time, 15 seconds apart. Kikkan started 45 seconds ahead of me, and I am absolutely not going to lie and tell you that I wasn’t a little bit motivated to see if I could make up any time on an Olympic gold medalist. As I finished my first 1.5-kilometer lap, I spotted her bright racing suit doubling back around a corner and entering the shooting range, and I started counting off seconds; I made it to 41 or 42 before I found myself on the same spot on the course.

Biathletes shoot at five targets between each lap. I hit my first nine shots in a row before missing my first one — but this comes with some pretty substantial caveats.

Typically, biathletes have to shoot from two different positions, standing and prone. In prone, they lie down and can prop their elbows on the shooting mat, making for a much more stable and accurate base. But to balance that, they have to hit smaller targets — a diameter of 1.5 inches, compared to 4.5 inches for standing, which means the standing targets are six-and-a-half times larger by surface area. As a beginner, I was shooting at the larger standing targets while prone — and I had the benefit of a stand that I could rest my rifle stock on.

I was feeling pretty good about myself for hitting nine out of my first 10. But by the time I came in to shoot for a third time, Kikkan had slipped out of sight, and after hitting my first two targets, I noticed a serious problem: fog. Inside my decidedly non-performance, kind-of-nerdy, Eyebuydirect.com glasses.

I proceeded to miss three shots in a row, then two more in my final turn at shooting.

My brilliant start, and my hopes of victory, had dashed by poor shooting (not to mention poor fitness). But really, this is the beauty of biathlon: Promising races can vaporize in a manner of seconds. And my final tally, 14 out of 20 shots, was still one better than a recent race by one of my favorite pros, Stina Nilsson of Sweden, who juuuuuust lost out to Kikkan on a gold medal in cross-country skiing at the 2018 Olympics, then switched to biathlon and has not yet achieved the same heights.

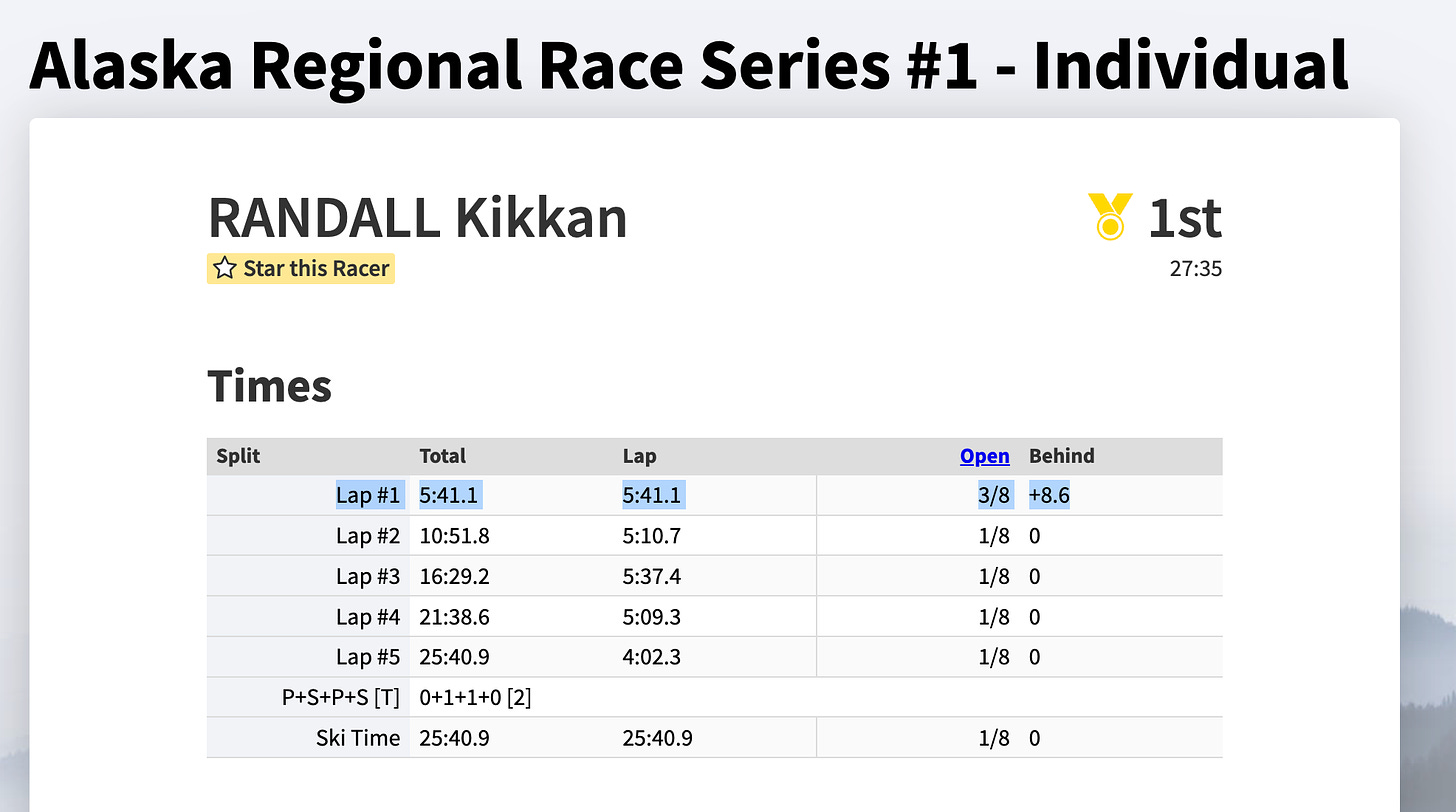

Nonetheless, let the results show what may be my proudest-ever athletic achievement: My first lap of the race was two seconds faster than Kikkan’s. However, she then proceeded to hit every single shot (or almost every single one — accounts differ), outpace me on all the other laps and absolutely obliterate the entire “open” division, winning by nearly three minutes.

I was chit-chatting with friends after the race when, over a speaker, the awards announcer started yelling my name. (Actually, they yelled for “Nate,” but this is a common enough occurrence.) It turns out I had achieved the impressive result of third place out of eight, behind, of course, Kikkan and Rachel. (Yes, the two women in the field destroyed the six men.) In addition to a podium photo with two Olympians, this result earned me a $1 billion bar of chocolate, and enough of a tale to merit inclusion in a Northern Journal newsletter.

This article is the work of Nat Herz (a regular FasterSkier contributor, and Producer of The Devon Kershaw Show), and is re-printed with the permission of Nat Herz and Northern Journal.

Northern Journal is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Nathaniel Herz

Nat Herz is an Alaska-based journalist who moonlights for FasterSkier as an occasional reporter and podcast host. He was FasterSkier's full-time reporter in 2010 and 2011.