Bobbing around in the middle of Lakes Huron and Michigan like a cork in a bathtub while staring up at the intimidating mass of the Mackinac Bridge tends to put things into a different perspective. My perspective was one of incredible insignificance. Everything around me was huge: the lake, the bridge, the distance, the current, and especially the stomach churning, energy sapping swells. I felt incredibly small. How does a guy end up in this position; trying to swim across the Mackinac Straits, a body of water known for its turbulence and ship sinking prowess?

For me, the journey began more than eight years ago, when I was suddenly stricken with a debilitating illness which sapped my energy and strength and deprived me of the ability to engage in physical activity any longer than a few minutes. This began when one day I was happily completing the Noquemenon Ski Marathon, and then, a couple of weeks later, I found myself unable to walk around my block. I’ve written about my situation previously, and the exact nature and description of my illness is irrelevant. Lots of people suffer sudden illnesses which radically change their lives. I was now simply lumped in with that group and was trying to find some sort of new normal, and a reset of sorts.

For years since my illness began, I had been trying to claw my way back to some level of physical activity— without success— to try to regain a vital part of myself which had been yanked away from me. I still had the desire to compete and push myself, the trick was getting my body to accept any significant workload without making myself sicker. The mind was willing, the body wanted nothing to do with it. When I looked in the mirror, I saw the same guy, but the guy looking back was somehow different— something hard to define was missing. Physical activity had become so intertwined with my self-identity that its absence was redefining who I was—in a way which I really didn’t like. Without it I was still kind of me, but also kind of not.

The road back was tedious, frustrating, and required strict discipline. I had to steadfastly adhere to a protocol of tiny incremental increases in output and work only within the narrowest window of what my body could handle; and never one bit beyond that. Any deviation from the plan would mean days on the couch struggling to regain my footing. My first attempt at a comeback with “real” exercise was about two years after my illness’s onset, after I had finally found doctors who understood and could help manage the symptoms of my condition. My first workout on the comeback trail consisted of exercising on a stationary bike doing three intervals of two minutes with a maximum heart rate of 79, followed by two days rest. This was my starting point. Exercising for six minutes at what had been below zone one and not even previously measurable as exercise was frustrating and seemed pointless. I also had a ceiling on increases in the length of total exercise time which was being limited to a 10 percent increase every three weeks, with an even smaller increase in maximum heart rate. If you do the math, that meant that I could go from two minute intervals to 2:12 minutes after three weeks. At that rate, it would take—and did take— years before I could exercise for long stretches of time like I used to. Another limitation was that any exercise performed where I was standing—and that’s almost everything—was more difficult for me to manage and came with more restrictions. That’s where swimming entered the calculation.

After five years travelling down this road, I had gotten myself back to the point where I could swim a half mile in open water. It wasn’t like any of this was a steady linear progression. There were huge setbacks and crashes along the way. There were also new found muscular and neurologic issues which had to be managed constantly.

Nonetheless, having this newfound ability led me to “compete” in a half mile race in the Swim to the Moon festival of races held outside of Hell, Michigan. Yes, there really is a town called Hell, and it’s actually quite picturesque. I had started at the half mile level, and the following year I worked my way up to the 5-k race which I again competed in this year. I had some unfinished business in that race and wanted to try and crack two hours; the closest I had come in two prior attempts was 2:02:55. But, I was confident that I had another three minutes in me.

Other than the 5-k race—which was a major accomplishment on its own—I decided that I needed to make a real statement to myself. The statement needed to be something bold and inspiring which spoke to my regained abilities, and previously unimagined possibilities. Most importantly, it needed to be something which I wouldn’t have considered achievable, or necessarily reasonable before my illness. I wanted this experience to be something that when I publicly announced it the general response would be “are you crazy?” Completing such an endeavor would send the message to myself that while I might not be what I was before my illness, that at least I was back at some level—a different level. That’s where the Mackinac Bridge Swim comes in.

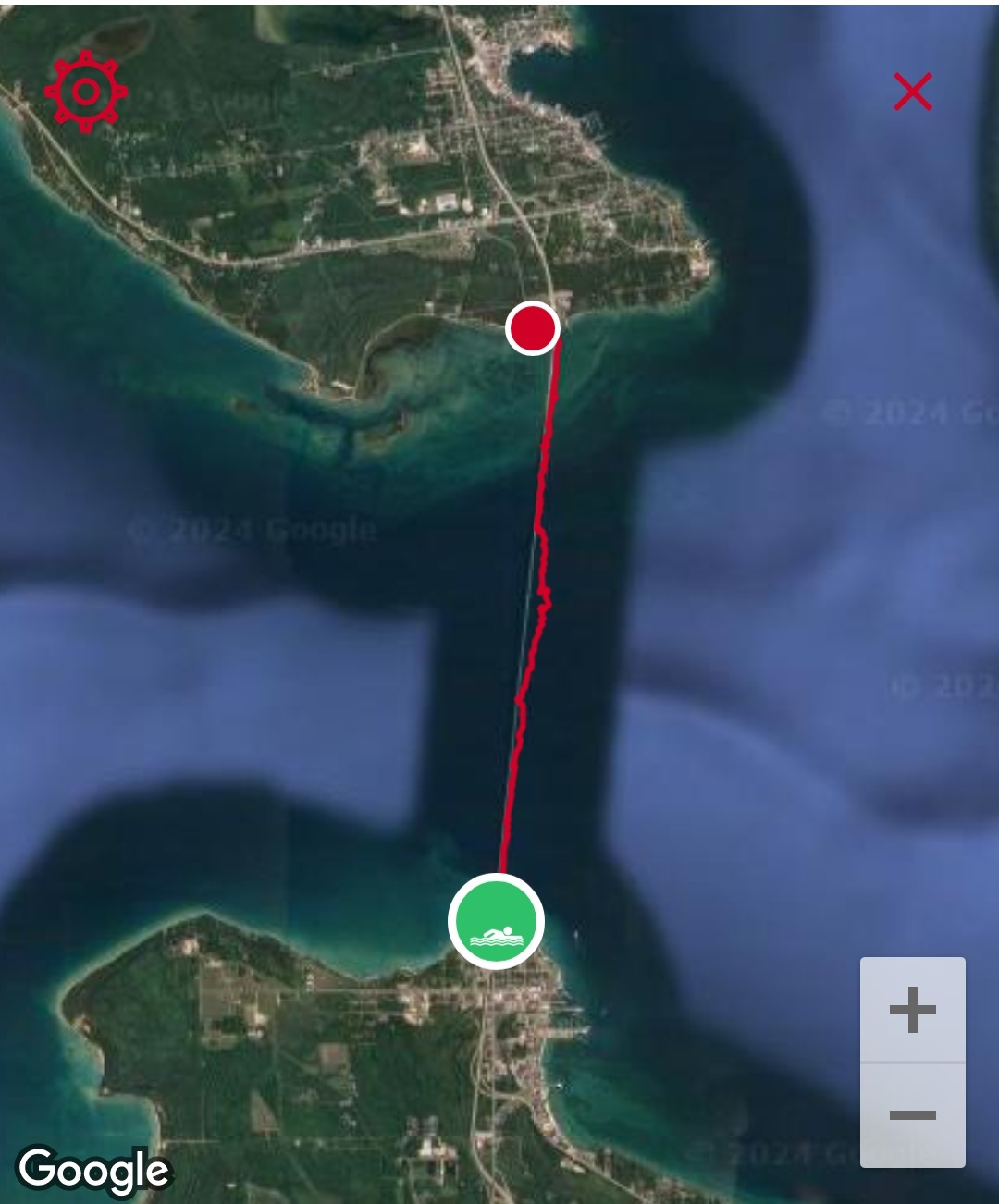

Before my illness I was a competent swimmer having completed too many triathlons to count, so I felt comfortable in the water. But I was never—and still am not—particularly fast. I had heard about swimming across the Straits years earlier, but the number of people who had done it was small and the logistics were daunting. The Mackinac Bridge is five miles long and the body of water it crosses is a little less than that. To swim the Straits, you need to cross about 4.5 miles of water, as the crow flies. As it turns out there aren’t any swimmers who can swim as straight as crows can fly.

The story of the building of the Mackinac Bridge is itself a fascinating and daunting saga worth reading about. There are several excellent books on the subject. (Mighty Mac The Official Picture History of the Mackinac Bridge is a good starter) The initial response to any construction proposals were similar to the response I wanted when announcing my bridge swim … are you crazy? For decades, the best engineers in the world said it couldn’t be done until a design genius by the name of David Steinman cracked the code of how to build a structure big enough to allow freighters to comfortably pass under it and to be able to withstand the winds and ice sheets of the Straits. The Mackinac Bridge opened in 1957 and is the longest suspension bridge between anchorages in the Western Hemisphere. It spans 26,372 feet. It is gigantic in every metric. How this seemingly impossible engineering feat actually happened is a story of persistence, ingenuity, and creativity—many of the same traits which I hoped to bring to bear on my new found goal. It seemed like the perfect match.

It was by chance that I then stumbled across an event called the Mackinac Bridge Swim. This is an organized event—not a race—which gives swimmers who meet the qualifying criteria an opportunity to swim the Straits in an organized safe fashion. Being an event instead of a race helps bring a level of safety to a potentially perilous undertaking. When people race, they tend to do stupid things. When they are trying to complete a goal, a certain amount of reason may prevail—maybe.

There are lots of logistics for organizers to arrange. The event includes obtaining permits from the Coast Guard, Homeland Security, and other agencies. Scores of motor boats and kayaks also need to be procured and organized to ensure safety. Then there are the freighters. The Straits are one of the busiest shipping channels in the Western Hemisphere. Great Lakes freighters are huge, incredibly fast moving, and don’t slow down for anything, including avoiding swimmers. So there has to be a plan for that—more on that later.

It was with more than a little trepidation that I signed up for the event, along with my wife, who for family reasons has a very strong emotional attachment to the Straits area. To make the summer-long training odyssey really complete, I again signed up for another Swim to the Moon 5-k race which would occur a couple of weeks after the Bridge swim, and also ended up registering for the Teal Lake Swim in Negaunee, Michigan, which is the weekend after the Bridge swim. It was now a full slate of summer swimming.

So that’s the long introduction to how I found myself bobbing up and down in the water under the Mackinac Bridge questioning my sanity and whether I had any rational thinking processes left in my brain.

As an aside, I’ve really enjoyed the shift during the summer from roller skiing to swim training. It may not bring the same fitness levels as ski training does, but it gives the body a break and the mind a reset. Prior to swim training, I had focused on summer ski training for over 30 years. The change felt good, and more sustainable. I also think it’s really valuable as we age to force your body to learn new movement patterns. It took a lot of brain power as I tried to master improving swim technique and to reprogram my body’s autonomic swim style. And once your reach a certain age, going through that process has to provide some type of neuroplasticity benefit.

There are a lot of similarities between long distance swimming and skiing. Much like a 50-k ski race, there are many variable components to work out before and during the event. There’s swim technique, which is very analogous to skating and striding. There are also gear considerations such as wetsuits—style and thickness, swim caps—thermal or thin, and swim buoys (inflatable safety tubes that attach to the waist by a line and are used if you need to rest and can’t tread water, but don’t aid in forward propulsion or buoyancy), and nutrition. A plan for these all needs to be sorted out before the race begins. Also, much like a ski race, several of the strategic components can’t be decided upon until the morning of the race when you can see exactly what conditions are like.

Nutrition is one of the trickiest parts since consuming food and swimming aren’t naturally complementary activities. Everyone has heard the admonition against swimming within an hour of eating. Well, you can consume food while you swim just like in a ski race, and you don’t get out of the water and wait for an hour-sorry mom.

There are almost as many ways to take on nutrition during a swim as there are people doing an event. But the big difference for the Bridge swim is that you can only consume what you have on you. There aren’t any boats handing out aid, and wetsuits don’t have pockets, so people contrive all manner of contraptions to try and tote sport drink and gels along with them.

After an entire summer of preparation, the race date of July 20th was finally upon us. Race morning looked clear and calm, as about 160 participants gathered on the beach at the base of the south side of Mackinac Bridge. Once we were in the water the calmness quickly dissolved. The unpredictable Straits current was quickly rearing its ugly head. After only a couple of minutes it became very obvious that things were going to develop differently than hoped for. Once we cleared the initial shoreline you could immediately feel the pounding of the waves and the force of the swells pushing you away from the bridge.

The swim is essentially south to north, and you are required to keep the bridge on your left and to stay within 100 yards of it as you are heading north. The current was pushing hard from the due west constantly driving you away from the bridge and requiring you swim on a diagonal to prevent being pushed off course. My pre-swim plan was to predominantly breath on the left so you could constantly see the bridge and better stay on the course. This plan quickly went out the window as each time that I breathed on my left I was hit with a wall of Lake Michigan water in my mouth. I quickly switched to breathing on the right. This isn’t unlike being in a ski race when conditions force you to V-1 on either the left or right side, but it meant that it was now even harder to stay on course.

After about 20 minutes we were well clear of the beach and things were not going well. I was struggling against the waves and the current which were both much more powerful than anything I had trained in. Because of this, I was using way more energy than I was accustomed to. Also, I was beginning to get seasick and dizzy; as it turns out, so was just about everyone else. Of equal importance was that because of being constantly on the verge of reverse peristalsis (ok–vomiting), I wasn’t able to take on any of my sport drink. Some people can do a three hour swim without nutrition— I cannot. The rumblings in my belly and pounding in my head were a clear message that I wouldn’t be able to drink much, if anything. At this point, after a scant 20 minutes, I already had thoughts about abandoning the swim. The negative thoughts were ramping up and gaining ground on me quickly. With about three hours of swimming ahead, I thought there was no way I could continue in these circumstances.

Over the summer I had developed the mindset that the only way I wasn’t going to complete the event was if they plucked my unconscious body out of the water. Well, the early sea sickness quickly broke that resolve, and I was on the border of quitting. But then, I began to think back on the longer journey— the two minute intervals on the bike— and the endless days laying on the couch exhausted. I began to think about how far I had travelled and what it had taken to get here—lots of tiny steps. I then made a new deal with myself. The new bargain I negotiated on the spot was, “just give it five more minutes, you can do almost anything for five minutes, right?” So that’s how it continued for another half hour or so—six or seven sessions of self-negotiation— until I hit the first anchor block.

The anchor blocks are huge concrete structures sunk into the lake bed which hold the 42,000 miles of wires which make up the main cables (that’s correct, 42,000 miles of wires) which support the span. The blocks are concrete giants and large enough to create calm water on their leeward side, which in this case meant there was a nice little section of flat water to rest in, which is exactly what I, and dozens of other people chose to do. We were all firmly clutching onto our float buoys while gathering ourselves as best as we could. I was able to choke down a few sips of sports drink and was starting to feel a little bit better about my chances of completing the swim.

As you continue your swim north from this point you soon really enter the heart of the matter as you are now swimming in the middle of the maelstrom created by the confluence of Lakes Michigan and Huron. You are also shortly reaching the point of the base of the south tower which supports the tops of the suspension cables. The towers are an intimidating 550 feet above the water’s surface and extend over 200 feet below the waterline. So, you’re essentially bobbing around the base of about a 40 story tall skyscraper with about another 14 stories below you.

As I neared the tower I was feeling a little bit better and was now getting ready for the mad dash between the two main towers which define the shipping channel. The channel is about 3,800 feet long, and an ominous 295 feet deep. In this void there is nothing except you, a few other swimmers you may see at times, the lakes, and any freighters which may come barreling down the pathway. Because of the fast moving freighters, there are very strict rules of conduct between the two towers. If a freighter is sighted, regardless of how close you are to one of the towers and being out of the shipping lane you must immediately swim to a safety boat; no negotiating.

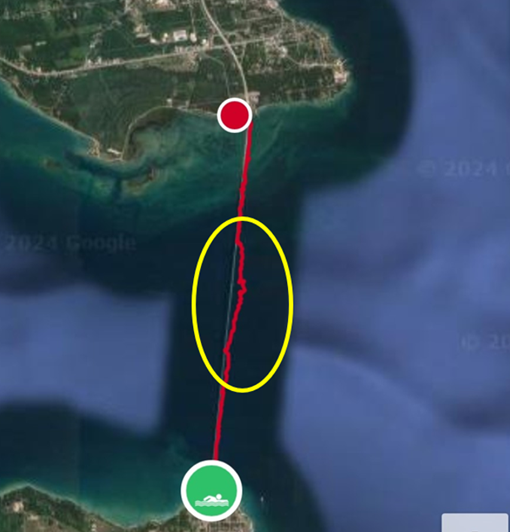

The increase in current in the shipping lane was very noticeable, and as I continued to swim, I saw that I was annoyingly close to one of the safety boats—couldn’t this guy see me? I began to get concerned that the swells might be large enough that the boat’s crew couldn’t see my lone figure flailing away in the water. The boat began to get closer and closer, and I began to get more and more anxious and annoyed. Only then did I realize what was happening. The current was so strong that it had pushed me far east and I was now in danger of being off the course and having my day come to a close. Once I realized this, I began to swim with my head pointed straight at the bridge. I was now swimming due west on a south to north course, while in the middle of the shipping channel; to say this was not ideal is a bit of an understatement.

After about 10 minutes of swimming due west, I managed to pull myself close to the edge of the bridge’s overhang. I was now only about a minute from the North tower and would soon have one of the swim’s critical stages behind me. The second (north) tower where the race’s initial time cutoff is measured. If you miss the cutoff (two hours), your day is done, once again no negotiating.

It was then that I saw the red flags on one of the safety boats and heard the volunteers yelling. This was the warning that a freighter was in the channel, and everyone had to get out of the water. I was so close to being free of the shipping channel that for a moment I considered pretending not to see the flags, fortunately that feeling only lasted for a second.

Freighters are huge, move fast, and cast gigantic wakes. But when you’re in the water and they’re heading straight at you, they take on an entirely different and downright menacing perspective. They now appear as incredible giant sea monsters aiming straight for you and appear to move at about the speed of a small plane. I didn’t argue with the volunteers and gladly clambered aboard the safety boat along with several fellow swimmers.

We were all safely clutching the railing while sitting on the stern of the roughly 25 foot vessel. We all had a forlorn grim look of concern and doubt on our faces. Most of us were feeling seasick and a couple openly questioned whether they should carry on. I put on a brave face and said that the worst was probably behind us—I was lying.

Before getting on board the boat, I had been feeling a little bit better. But the boat was rocking and being tossed about more than I had been while in the water. I was getting really sick again and was again questioning carrying on. I renewed the five minute bargaining sessions process.

The boat took us out of harm’s way from the freighter and deposited us by the north tower. I had only been about a minute away from the tower when I was pulled from the water, but because the captain didn’t want to get too close to the bridge, I was more than a minute away from the tower when I said thank you to the volunteers and farewell to my fellow swimmers and jumped back into the water. I was rewarded by having my goggles ripped off my face and had to struggle to put them back on and drain the water from them. I never was able to find out if all of my shipmates chose to make it back into the water, or if they completed the swim.

After a couple of hard minutes of swimming I was bobbing around the base of the north tower and actually able to take some time to admire its grandeur. But there wasn’t much time to take in the view. A lot of time had passed since the start, and I was beginning to get fatigued. I hadn’t been able to take on any nutrition since the first anchor block and the effects were starting to show. Unlike a ski race, if you’re in trouble, you can’t just pull over and take a couple of relaxing breaths or slow to a crawl to gather yourself. The lake keeps pounding away, and every second spent floating in the water without moving north is a second of energy lost which could have been used to swim.

I put my head back down into the water and doggedly continued my journey north. At about the time I reached the north anchor block the effects of lack of nutrition really began to take their toll. My calves began to cramp, then my hamstrings. Cramping is the bane of long distance swimmers’ existence. I still had miles to go, no way to take on any food to help with the cramping, and was still being pounded by the big swells. Things were not going well—again. I was once again back to bargaining with myself to swim in five minute increments. “Just give it five more minutes and things may turn around.”

I trudged north for what felt like an eternity, but was probably only 30 minutes, and I was suddenly struck with a great sense of relief due to a Mighty Mac engineering quirk. As I mentioned, the construction of the bridge had been deemed to be an engineering impossibility. A remnant of a failed bridge attempt from the 1940s is a 4,200 foot long causeway extending from the north side of the Straits which the successful builders incorporated into their design to save time and money. I had just hit the point where I was on the leeward side of this causeway and was at long last comfortably sheltered from the swells and waves. More importantly, for the first time all day the fickle Straits’ current had shifted, and I had a nice current going my direction. It’s a lot like being on a century bike ride battling the wind all day when you hit the turnaround point and the wind is now at your back. I finally felt like I could do something resembling swimming and not just flailing in the water trying to survive. I had known about the causeway and had been warned that this spot was a trap. From here you can see the north shore, and it seems like you are almost done. The reality is that from this point there is still about a mile to go. But the sheltered swimming was such a relief that my spirits immediately lifted and for the first time all day I felt like the odds were finally in my favor. I still had about an hour to go, and a lot can happen in an hour, but now my mindset was better than it had been all day, and with it my body began to respond. I even tried to take on some sports drink, but quickly found that things in the digestion department hadn’t changed.

Even though I was tired, it felt great to swim aided by the current, instead of fighting it, and it felt wonderful to be able to use real swimming technique. As you head north along the causeway, there is one more major stumbling block to overcome. You are swimming on the east side of the bridge causeway which is solid rock. The finish is on the west side. To get to the finish, you have to swim under the causeway through a large culvert. Again, due to the confluence of the two great lakes, the current in the causeway can be fierce. We had been cautioned about this by the event’s organizers and had been urged to save some energy to fight the current. You have to push hard against the current for about a minute, which amounts to doing one hard interval after three hours in the water. But it turned out to be very manageable, and compared to the pounding of the open water was actually somewhat anti-climactic.

The other side of the causeway was a bit of another false finish. After you emerge from the causeway’s gaping exit, you are now on the Lake Michigan side of the bridge. The geographic geometry changes and the waves were now smacking me straight in the face. With about 15 minutes to go to reach the finish it was Lake Michigan’s last ditch effort to keep me from finishing. It sounds silly, but it felt like things had gotten personal. But at long last the end was now in sight. A huge American flag hung from the top of a fire truck’s extended ladder in the finish area to highlight the finish line, or in the event’s parlance, the “I did it line.”

After several hours in the water most people’s legs are like rubber and fortunately there are volunteers to help swimmers walk onto the shore, otherwise, you would literally have to resort to crawling on your hands and knees. I emerged shaken and stirred—three hours and ten minutes from when I had started— and greatly relieved to be finished.

Every participant was greeted by the event’s organizer, Eric Hansen. When he asked me how it went, I replied, “it was really a lot rougher than anything I had imagined.” His response was, “I didn’t say it was going to be easy, just that it would be worth it.” He was right.

I stumbled my way along the beach and tried to find my relatives and my wife, who I had assumed had beaten me to the finish. The horizon refused to stay level and jumped up and down like a stuttering old movie reel that wasn’t being played properly as my equilibrium tried to re-establish itself. I found my relatives, and my wife, but she was crumpled over in a chair with her head between her legs. The seasickness had completely overwhelmed her— and many others— and she had to withdraw. But she is not easily deterred and has already made plans for next year’s revenge tour— I’m on the fence about a rematch. I feel like I kind of got away with something and don’t necessarily want to tempt fate.

After the event people asked me how it was and if I would do it again. Swimming across the Straits was incredibly hard. It wasn’t the hardest physical thing I’ve ever done. I’ve had plenty of ski races where I felt way worse for days after. But it was unquestionably the hardest athletic event mentally I’ve ever done. The relentless intimidation of the big water, and the dire effects of seasickness sap your energy, focus, and desire unlike anything else I’ve ever encountered. It’s like that old joke about wrestling with an 800 pound gorilla; you don’t quit when you’re tired, you quit when the gorilla’s tired.

Open water swimming is kind of like that. Lake Michigan doesn’t care how tired or sick you are. It doesn’t care about how long your journey to get to this place has been. It just keeps on pounding away. Maybe it’s a nice day and the lake will be like glass, and you will have a beautiful swim. Or, maybe, it’s like what we experienced where it’s like a washing machine and you feel and look like a ragged garment that was on the spin cycle way too long—but just like doing the dirty laundry, it was worth it.

Please return to FasterSkier for Part II of the Old Man and the Bridge.