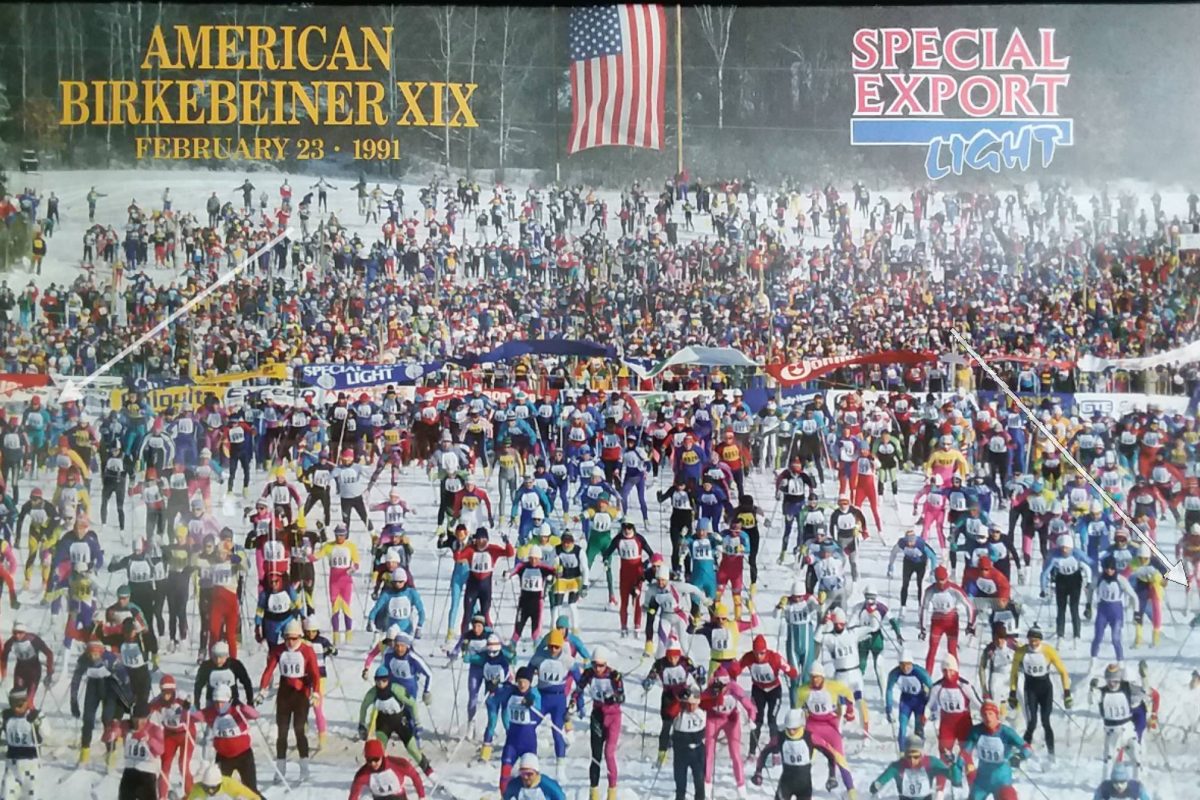

On the tails of a season North American skiers might still be smiling about, it could be hard to think about how climate change might negatively impact our small sport. It is convenient to have selective memory and recall a phenomenal crust ski on the Lost Man Loop off of Independence Pass in Colorado on June 10th of this year, rather than remembering running the same loop when it was almost completely dry on July 1st of 2018. It is convenient to forget the patchy snow conditions at my local ski area, Spring Gulch, that made February of 2018 look more like April. Or to forget that 2017 was the year without the Birkie. Maybe that is just me.

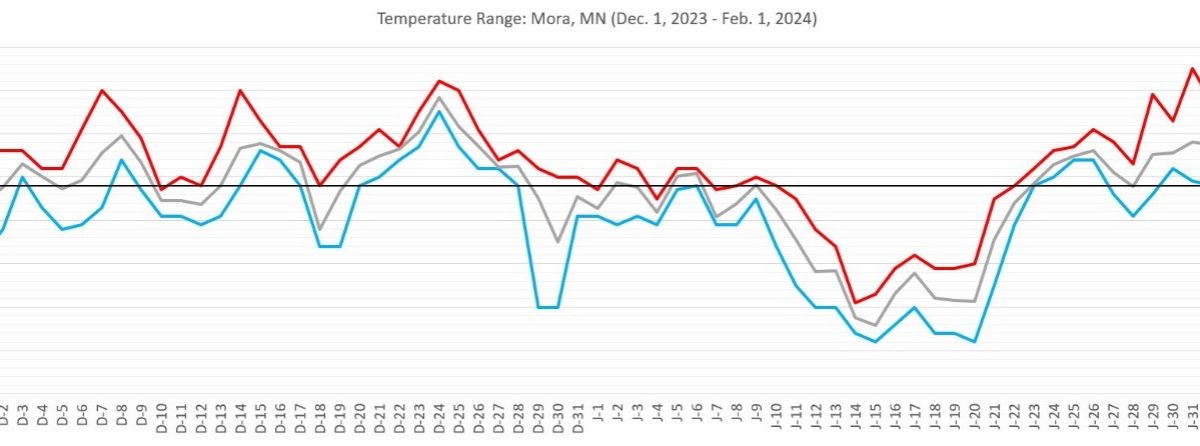

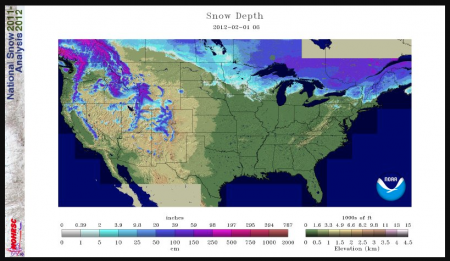

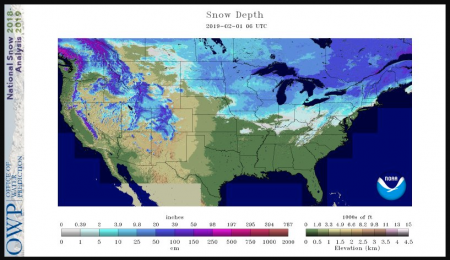

By the numbers, in February of 2019, 38.7% of the continental United States was covered with snow. In contrast, in February of 2018, only 28.6% was covered. In February of 2012, a year of destructive wildfires akin to 2018, the coverage was only 22.9%. The overall season this year was well above average for snowfall in Colorado; last season was substantially below average. In case you also experience a selective memory and are unable to recall how the snowpack in these years affected your local trails, consider the disparity between snow coverage graphs of the Continental U.S. in February of 2019 versus February of 2012.

According to a 2012 study, only about 55% of alpine ski areas in the Northeast will be able to maintain a 100-day season through 2030, thereby affecting the financial viability of the resort. Presumably, this impact will be amplified for cross country ski areas, which tend to be at lower elevations without as prevalent access to snowmaking. In reaction to these changes, ski centers nationwide have already begun making modifications to their trail systems.

To learn about trail modifications that are within financial reach of a cross country ski area, FasterSkier spoke with John Morton, a trail designer based in Thetford, VT whose resume of trail projects extends to premier nordic ski destinations nationwide and competitive venues. The conversation focused on what Morton considers “simple improvements”, rather than more intensive actions, such as harvesting or making snow.

Morton’s resume in nordic sport is as long or longer than the list of trail projects he has worked on. Morton competed in biathlon during the 1972 and 1976 Olympics, coached the US Biathlon Team in 1980, then acted as Biathlon team leader for the subsequent three Olympic Games. He was inducted into the U.S. Biathlon Hall of Fame in 2009. Morton has been Chief of Course at the World Cup and US National Championships for Biathlon at Soldier Hollow and has worked as a technical delegate or referee at several other high-level competitions. He was also the head coach at Dartmouth College in the ’80s.

It was from his time at Dartmouth that Morton became interested in trail building, leading to the eventual start of his company, Morton Trails. He had been hired onto the Dartmouth program by another well-known name in the field, Al Merrill. Merrill, who Morton described as being “knowledgeable in all facets of nordic skiing”, had been a mentor for him during his years as a coach. Merill contacted Morton while working on one of his noteworthy trail design projects at Giants Ridge in Biwabik, Minnesota because the venue was intended for both cross country and biathlon. Merrill consulted Morton with questions about the latter and later reached out again to help revise the Dartmouth ski system at Oak Hill.

“I learned a lot, and I realized that some of the decisions he was making in terms of where the trail would go and how it was configured were the same decisions I would have made if I were working by myself,” said Morton in a call. “So I felt confident that having skied a lot and raced and coached in a lot of different locations, I had developed a certain sense of how good trails should feel and conversely what you want to try to avoid in terms of enjoyable cross country ski trails.”

Morton began to notice the effect that a poor winter had on training opportunities during his time as a coach, which is when he began honing his knack for identifying and pursuing optimal terrain.

“The pattern seemed to be that there we would have several years where it was really difficult conditions, and we might get a good snow storm, but it would end with rain,” he recalled. “So what looked like it was going to be a promising snow cover, ended up being slush or worse, was just washed away by the rain. So you ended up being very skillful in trying to find places, little pockets of high elevation or in the shadow of a hill or a mountain where it might drop more snow than it did even relatively close by. We ended up finding a lot of those places where for some pretty subtle reasons, it ended up just getting more snow and often times retained it better.”

While the impacts of climate change have become more pronounced, Morton does not see the decline he feared in nordic ski venues.

“I was definitely concerned about this little niche [of cross country skiing] and if climate change was really going to impact that negatively, are there going to be a lot of these nordic centers that basically are no longer able to function?” he asked rhetorically. “But what has been interesting is that a lot of the facilities have made the choice to do whatever it takes to continue to provide good skiing for their customers. Sometimes it’s modest improvements, sometimes it’s really biting the bullet and raising money and looking at snowmaking.“

He added that the sense of urgency to react to the unpredictability of winter has kept him busy as a trail designer, rather than put him out of business.

Morton has presented at trail conferences and consults on the topic of adapting to climate change and maintaining or creating trail systems that mitigate snow loss and allow optimal ski conditions during suboptimal winters. Many ski areas recognize a need for improvements, but are not interested in or do not have the budgetary resources to consider snowmaking – a capital cost he estimates between $150 and $250 thousand per kilometer for a pipe and hydrant system. This upfront investment does not include operating cost. A single kilometer of trail also requires approximately 270,000 gallons of water to cover with a one foot base of snow. For these ski areas, he suggests a hierarchy of relatively low-cost interventions that may make a large impact.

“A lot of these suggestions are quite obvious,” he said. “But they are often things that are overlooked and even with places that are really knowledgeable and have a really skilled staff, you sometimes notice that these simple things could help the quality of the skiing.”

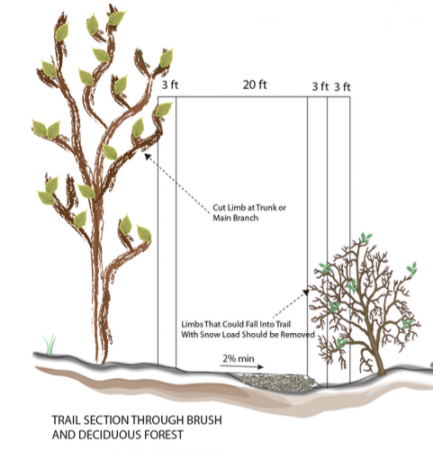

As the majority of ski trails are through treed terrain, the first intervention he suggests is to limb branches to open the canopy above the trail allowing more snow to collect on the trail itself, rather than on the trees. He recommends using a telescoping pole saw, preferably machine powered, to make it easier to cut higher above ground level.

“Just by walking on the surface of the trail, you can reach up 16 to 20 feet [with the pole saw] and limb off all of the overhanging branches, because in the wintertime, those branches hold snow, and the snow doesn’t always reach the trail. So I’d say that is number one and probably the simplest.”

The next step is to further widen the trail if possible, which furthers the trails ability to collect falling snow.

“A lot of original early traditional cross country ski trails are quite narrow,” he said. “Back in the days where it was just classic and if they were groomed at all they were groomed with a snow machine. Nowadays, if you want to have skating and classic skiing, you need a trail that is probably at least 12 feet wide and ideally more like 16 feet wide.”

He added that this width needs to be substantially greater if the area plans to be a premier competition venue, as FIS homologation standards require 9 meters (~30 ft) of width on uphills for a freestyle course and 6 meters for a classic only course.

“Step number three would be carefully looking at the surface of the trail itself,” he continued. “A lot of trails, especially trails that don’t get a lot of use in the summer, they may have rocks and roots and places where erosion has negatively impact the surface of the trail. So any efforts that the owner or the management of the facility could take to smooth out the surface of the trail would allow grooming on less snow.

“That probably also involves improving the drainage,” he added. “It might mean putting in more culverts. Often times, if a trail is older and has been used for quite a while, you’ll find that there are places that are eroded. Along the edge of the trail, there might be a fairly significant ditch. So if you take an excavator or a bobcat or something like that and mellow out those ditches so they are more like a swale, then that effectively becomes part of the ski trail rather than an obstacle along the side of the course.”

He also explained that wood chips, hay, or other organic material could be used to improve the surface of the trail.

While these improvements are “simple”, they do require manpower and potentially some expense, but Morton pointed out that many ski areas are able to recruit volunteers to help get much of it done. The more costly alternative to this would be to hire a landscaping crew to do the work or a logging contractor, depending on the work that needed to be done. While the latter could certainly be costly, he added that in some cases, if the trail system is located in a wood lot with quality and valuable timber, the cost of logging might be completely offset by allowing the company to selectively thin the surrounding forest.

If a volunteer or work crew member was proficient in operating large machines, Morton highly recommends considering renting an excavator.

“Excavators are extremely versatile and efficient machines,” he said. “These days, most trails, even trails intended for World Cups or very high-level competitions, they’re almost all built exclusively with excavators now.”

It may cost $150 per hour to rent and operate, but with a skilled operator, he can attest that a large amount of work can be completed within a week at a total cost of approximately $6000.

In regions that are not treed, another relatively low-cost option to consider is snow fencing or planting coniferous trees along the trail in the direction of the prevailing winds. As the wind passes through the fence or the branches of the trees, it slows down, dropping any snow it is carrying on the leeward side of the fence, ideally along or on the trail. Not only does this help to accumulate snow that can be groomed in, but it also prevents large drifts from occurring, which can be difficult to break up with smaller grooming equipment. It also may prevent newly fallen snow from blowing off of the trail before it can adhere to the layer below or be rolled in.

If a trail system is not able to maintain sufficient snow coverage of its trails using these methods, they might consider implementing more intensive measures, such as harvesting and spreading snow from a nearby site that might be a pocket of better accumulation. Some areas may need to consider rerouting the network in north facing or higher elevation terrain. Before cutting new trails, Morton cautions against choosing what might seem to be the easiest path.

“You can look around and the number of different nordic ski facilities, you can trace them back to the founder or the originator, and very often that person went out with a chainsaw and started cutting,” said Morton. “And oftentimes, it involved the path of least resistance. They’ve got a power line and they realized that if they just made a cut of half a mile or so, they could go out the power line, cross over, and come back on an old logging road, and then in effect, they’ve got a loop. But that type of evolution and path of least resistance rarely makes for the best skiing.

“And it’s relatively convenient and relatively inexpensive,” he continued. “But power lines and logging roads are not always designed with recreation in mind. So my recommendation is that an intention to extend the trail system, try to think of the big picture and say, ‘How will this fit in with the overall network? Are there some trails that we really should abandon because they’re no longer useful or suitable? What are the functions or the extensions of the extensions or the additions?’”

This reflection process might include considerations of whether a beginner trail is needed, which would limit the extension from areas that have large climbs or descents. But if the area is looking to cater to the training and competition opportunities for developing athletes, extending into the more technical terrain might be favorable.

He also suggested making trails directional both for the sake of skier safety and enjoyment.

“I’m a big advocate of one-way traffic,” he stated. “You can get more people on the trail without them realizing how crowded it might be if it is one-way traffic. And you can design a descent to be fun and safe and technical, but that climb would not be enjoyable if taken in reverse.”

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646