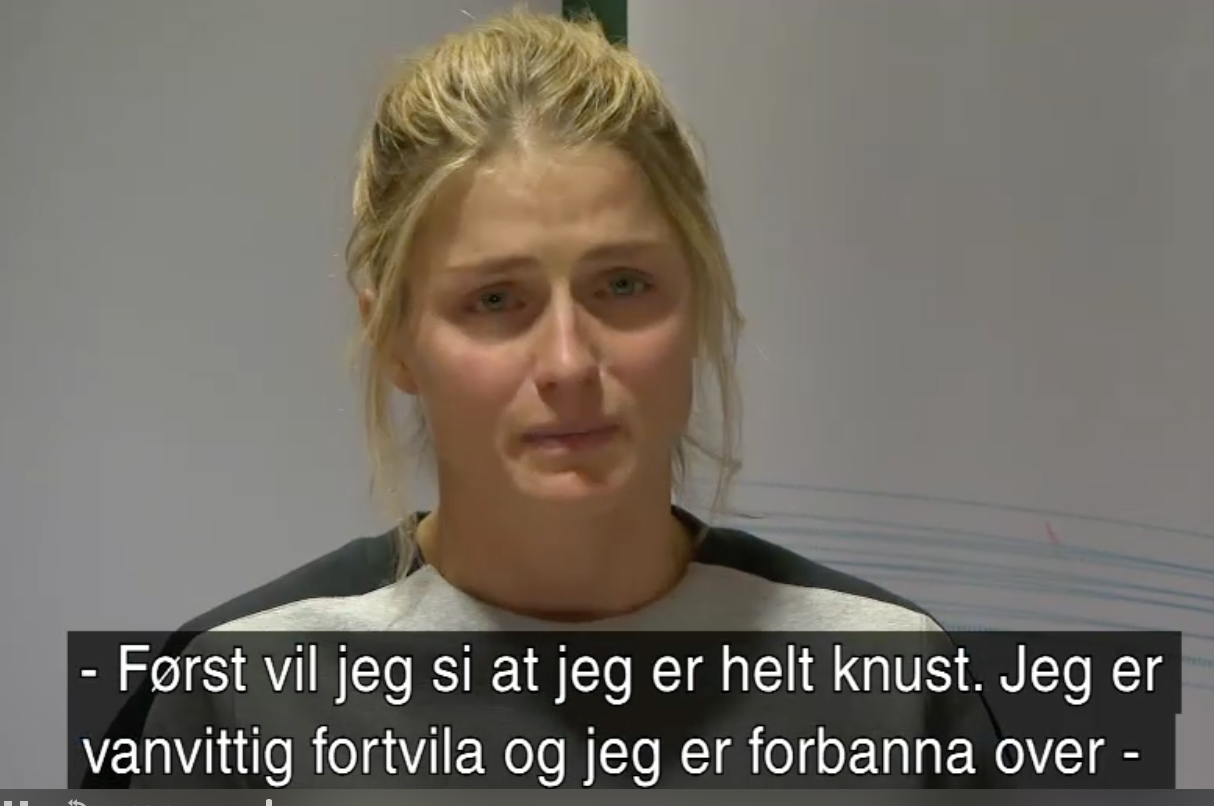

As previously reported on FasterSkier, Norwegian superstar Therese Johaug recently saw her suspension increased to 18 months following a ruling from the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) that overturned the 13-month suspension previously imposed by Norwegian anti-doping authorities.

The math is obvious to any fan of the sport, if absent from the CAS decision: A suspension start date of October 2016 plus 18 months equals April 2018. Johaug will miss the next Winter Olympics in February 2018.

FasterSkier separately addressed the factual question of what happened that led to Johaug testing positive for the steroid clostebol. That article did not consider the question of why 18 months was the suspension chosen. This piece tries to fill in that gap, by exploring the legal analysis of the CAS decision and the principles that the court applied in reaching this decision.

This analysis begins by looking at how criminal sentencing usually works, then applies these general principles to Johaug’s case specifically.

(Wonkish aside: This approach necessarily elides somewhat the distinction between criminal sentencing and a period of ineligibility from sanctioned athletic performance, which is closer to a civil remedy. It is worth emphasizing that Johaug has not been charged with breaking the criminal laws of any country, and is extremely unlikely to face criminal charges. However, the use of the basic principles of criminal sentencing is helpful here by analogy, as a way to think about set ranges of punishment, degrees of fault, and mitigating and aggravating factors.)

Sentencing Law 101

Criminal sentencing in American courts follows a basic three-step process. First, what is the crime of which someone has been found culpable, following either a jury trial or (more frequently) the entry of a plea as part of a plea-bargain?

Second, what is the sentencing range set for this crime? In state courts, this is a matter of state statute. In federal courts, the federal sentencing grid controls. In either sovereign, there is a gradation of offenses, and different sentencing ranges for more or less serious versions of each crime. For example, there may be a presumptive range of 3-6 years for first-degree assault, 1-3 years for second-degree assault, or 0-1 years for third-degree assault, with the ability to go much higher or lower depending on the specifics of each crime and a defendant’s criminal history.

And third, once the relevant sentencing range is known, what is the appropriate sentence within that range? And/or is there something so remarkably serious, or not-serious, about this offense that the sentence imposed should be above or below this range?

Presumptive sentencing ranges represent a compromise between uniformity and discretion. The elimination of unjustified disparity is a central goal of sentencing; within reason, the same people who commit the same type of crime should receive the same type of sentence. But it is also important that the system be able to adapt itself to any particular defendant, and the especially sympathetic or damning facts of a specific case. The law, as they say, is a human enterprise.

Turning to Johaug: What is the offense?

Applying these principles to Johaug’s case, Step 1 is easy. The relevant facts about what happened are effectively undisputed.

Here’s the CAS, in its recent written opinion, summarizing FIS’s view of the lower-court decision from the Adjudication Committee of Anti-Doping Norway:

And here’s Johaug’s view of the facts:

And here’s the court’s take:

Not much to argue about here – however much Johaug was at fault for what happened, everyone agrees that this is what happened. The often-tortured threshold question of how a prohibited substance entered an athlete’s body (think tainted meat, spiked supplements, the chimeric twin theory, etc.) was not an issue here. (See here for more on the facts.)

What is the appropriate suspension range for this offense?

Figuring out the baseline range for this offense immediately requires a resolution of the athlete’s mental state (or mens rea, to use the official Latin phrase that literally translates as “guilty mind”). This is because the presumptive suspension range depends on Johaug’s mental state.

The central legal question in this case was whether Johaug acted with “No Fault or Negligence” or whether she acted with “No Significant Fault or Negligence.” Johaug argued for the former; FIS argued for the latter. (Spoiler alert: the court agreed with FIS.)

Fault is defined by the World Anti-Doping Code (WADA Code or Code) as “any breach or duty or any lack of care appropriate to a particular situation.” This is very similar to the definition of this concept in American criminal and civil law.

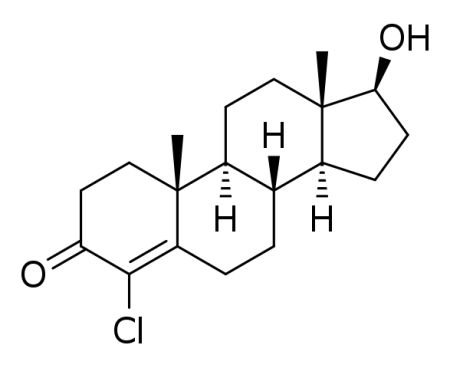

No Fault or Negligence, meanwhile, requires the athlete to “establish[] that he or she did not know or suspect, and could not reasonably have known or suspected even with the exercise of utmost caution, that he or she had used or been administered the Prohibited Substance or Prohibited Method or otherwise violated an anti-doping rule.” (Capitalized phrases are defined elsewhere in the Code. The Prohibited Substance, in this case, was clostebol.)

Notably, the middle clause of that definition, about not being able to know this even after exercising utmost caution, means that “no fault” is another legal term of art. That is, the term has a specialized legal meaning beyond the plain meaning of the normal English words “no fault.”

In this case, the WADA Code definition of “No Fault or Negligence” is a more difficult standard for an athlete to meet than simply the general, non-legal concept of “no fault” — an athlete has to establish not only that she did not know or suspect something, but also that she could not reasonably have known or suspected this even if she exercised the utmost caution. This is a harder standard to meet than the normal meaning of “no fault.”

The commentary to Article 10.4 of the WADA Code shows how hard this really is: this article “will only apply in exceptional circumstances, for example, where an Athlete could prove that, despite all due care, he or she was sabotaged by a competitor.” By contrast, the Code notes by way of example, the No Fault standard would not apply in a situation involving “the Administration of a Prohibited Substance by the Athlete’s personal physician or trainer without disclosure to the Athlete.” As the commentary cautions, “Athletes are responsible for their choice of medical personnel and for advising medical personnel that they cannot be given any Prohibited Substance.”

And finally, No Significant Fault or Negligence adds some degree of culpability to the No Fault standard, but not a significant amount: “The athlete or other Person’s establishing that his or her fault or negligence, when viewed in the totality of the circumstances and taking into account the criteria for no fault or negligence, was not significant in relationship to the anti-doping rule violation.”

(“Totality of the circumstances” is a common legal phrase that means, well, exactly what those English words sound like. The emphasis is on everything going on in a case rather than on one thing in particular – a court is directed not to apply a single test to one part of a set of facts, but rather to consider everything that is going on when it makes its decision.)

Johaug’s arguments about her degree of fault

Johaug, through her lawyers, argued first that she had acted with no fault. (CAS opinion paragraphs 122-32.)

She argued, among other things, that she was contractually bound to follow her doctor’s advice, that she had suffered lip sores before and had no reason to suspect that treatment of the same issue would present any risk this time, and that it was very reasonable for her to believe that her doctor had done any necessary checks on the medicine’s legality in the ca. 24 hours that he had it in his possession before he passed it on to Johaug.

Johaug argued in the alternative that, even if she had acted with some degree of fault, it was so minimal that it should be classified as no significant fault rather than as anything more serious.

The difference between No Fault and No Significant Fault is hardly academic. The differing levels of culpability translate to vastly different potential suspension ranges.

If Johaug were able to establish that she bore no fault, then no suspension would be imposed. See WADA Code art. 10.4.

If, by contrast, she had even the relatively small amount of fault that rose to the level of no significant fault, then she faced a maximum suspension of two years, which could be reduced by no more than half, or down to one year. See WADA Code art. 10.2.1, 10.2.2, 10.5.2.

And this range (1-2 years) is down from a baseline suspension of four years, the presumptive range for an intentional anti-doping violation (everyone involved in this case agreed that this was not intentional). See WADA Code art. 10.2.1. As we all learned on the elementary school playground, intentions matter.

(And this will be visited later, but it’s also worth pointing out that the four-year baseline suspension was implemented in 2015; before then, intentional doping offenses earned a two-year suspension. Times change.)

FIS’s arguments about Johaug’s degree of fault

FIS had a different view of the significance of Johaug’s doctor’s involvement in this case, and of Johaug’s ability, or lack thereof, to delegate any portion of her anti-doping responsibilities to a third party. FIS highlighted several portions of Johaug’s contract with the Norwegian National Team that seemed to suggest that Johaug retained a personal duty to refrain from using substances that may violate WADA rules.

As FIS argued, “The duty of care to avoid doping is personal and remained with Ms Johaug at all times.” (para. 155) FIS continued, “The athlete’s personal duty of care may include asking a medically trained person about doping risks of a certain product, but that is only one of several precautions that must be observed. An athlete may not blindly rely on a doctor’s answer, especially when the doping risk is so obvious, as in the present case.” (para. 156)

FIS outlined several additional steps that it argued Johaug could have taken on her own, such as reviewing the patient information from the Trofodermin package, searching for information about this medicine online, or checking the active ingredients of Trofodermin against the WADA prohibited list. (para. 165) FIS also critiqued Johaug for not completing a required anti-doping education program until after this violation came to light. (para. 173)

FIS argued that Johaug’s culpability was in the middle range of No Significant Fault, meaning that a suspension of 16-20 months was appropriate. (para. 167-74)

The court’s decision about Johaug’s degree of fault

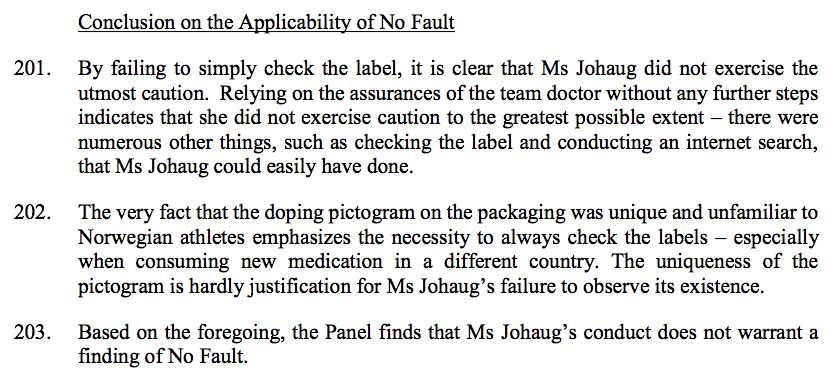

CAS ultimately found that Johaug had not acted with No Fault. In reference to the “utmost caution” standard in the WADA Code, discussed above, the court noted:

The court based this conclusion on several of its prior decisions, as applied to the facts of Johaug’s case.

For example, in one case, the athlete applied Trofodermin without checking its content; the CAS panel found that an athlete fails to fulfill his duty of diligence when he or she could have learned that a medicine contained a prohibited substance by reading its packaging or notice of use. In another case, the CAS underscored that an athlete has the personal responsibility to check assurances given by his or her doctor. And in many, many other cases, the court previously held that an athlete has a personal duty of care to comply with anti-doping regulations, and cannot delegate away those responsibilities to a third party such as a team doctor.

From a policy standpoint, the court observed: “The Panel remarks that if athletes were allowed to escape their personal duty by passing it on completely to an expert in anti-doping (such as a specifically qualified doctor), this could create a more advantageous position for wealthier athletes who have more resources to engage experts, leading to potentially unequal treatment in assessing compliance.” (para. 212)

What is the appropriate length of suspension within the established range?

The conclusion that Johaug had acted with no significant fault (or “NSF”) meant that the relevant suspension range was from 12 to 24 months. Within this range, the court made further distinctions as follows: “within the NSF category, a greater degree of fault may lead to a sanction of 20-24 months, a normal degree of fault may lead to a sanction of 16-20 months, and a light degree of fault may lead to 12-16 months.” (para. 208)

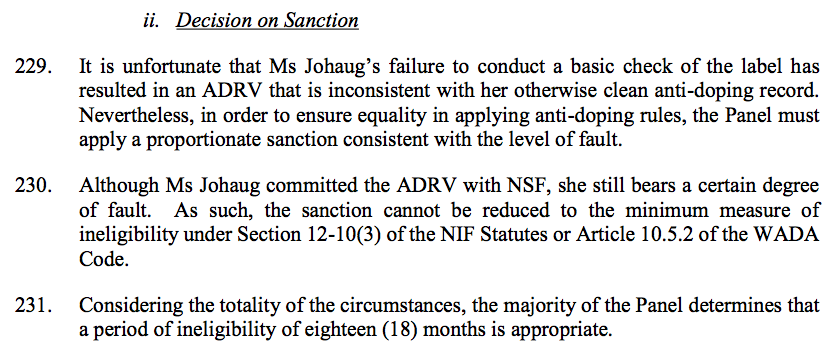

The court found that a normal degree of fault was present in this case, which made for a range of 16-20 months. The court ultimately imposed a suspension at the middle of this range, or 18 months. Johaug would not be going to the Olympics.

Tangent: About those Olympics, anyway

We’ll get to what the CAS considered in its decision in a second. But here’s something it officially did not consider: The fact that an 18-month suspension would keep Johaug out through the 2018 Winter Olympics, while a 13-month suspension would not. It begs credulity to suggest that the CAS panel was unaware of Johaug’s Olympic aspirations or the implications of this timing. But the 2018 Olympics appear nowhere in the court’s explanation of its reasoning, and were officially given no weight in its decision.

This is consonant with the WADA Code. The document makes clear that the determination of an appropriate suspension length should be an abstract one, free from considerations of the implications of a given suspension length: “the fact that the Athlete only has a short time left in his or her career, or the timing of the sporting calendar, would not be relevant factors to be considered in reducing the period of Ineligibility under Article 10.5.1 or 10.5.2.” (WADA Code App. 1)

Johaug’s attorneys were undeniably aware of issues surrounding the timing of the sporting calendar, and so understandably mentioned this in their appellate arguments. As the CAS summarized, Johaug argued in part that an extension of her suspension period past November 2017 “would negatively impact her chances [of] being selected for the Norwegian Olympic team due to the timing of the race season which starts in November. She explained the importance of the 2018 Olympics for her as she has never won a personal Olympic gold medal.” (para. 223)

But the CAS found that this was not a “relevant consideration[]” with respect to the appropriate sanction. (para. 224)

The court cited the WADA Code excerpt given three paragraphs above. It also noted a case from 2010 in which the CAS declined to consider the fact that a cyclist would have difficulty obtaining a contract with a professional cycling team during the 2011 season.

Back to the appropriate length of suspension

So what did the court consider? It adopted a suspension scheme from an earlier decision (a 2013 case involving Croatian tennis player Marin Čilić) suggesting that a “normal degree of fault” merited a sanction of 16-20 months. The panel, or at least a majority of it (that is, two out of three members), found that this range applied, “Given Ms Johaug’s overall circumstances.” (para. 208)

This conclusion was based in part on Johaug’s long experience as an international athlete subject to anti-doping protocols, including taking roughly 140 doping control tests. While the panel was sympathetic to Johaug’s lip injuries and training stress, the court found that she should have been aware of her personal requirements, and should not be allowed to completely delegate her duties to a team doctor.

Finally, the court considered, but ultimately rejected, Johaug’s argument that a longer suspension would be disproportionate. (The principle of proportionality, the notion that the punishment should fit the crime, is present in both “normal” criminal cases and in CAS cases involving suspensions from athletic competition.)

Specifically, the court noted Johaug’s claim that punishing her with a suspension of any length would be disproportionate to her fault in this instance, where she simply “did as all athletes are always told to do and as she was contractually obligated” by consulting with her doctor and following his advice.

But the court reiterated its conclusion that “athletes are required to perform their anti-doping obligations with utmost care, which in practice includes reading labels and packaging as a basic minimum. Further, delegation to a third-party, even to a highly qualified sports doctor, is not an acceptable justification.” (para. 220)

The court’s conclusion

The final CAS decision reflects a direct application of the WADA Code and a concern for proportionality. As the court concluded:

(“ADRV” means “Anti-Doping Rule Violation.”)

The court’s conclusion analyzed

The most important determination in this case, legally speaking, was the conclusion that Johaug had acted with some fault, rather than with no fault. This took the no-suspension provisions of WADA Code Article 10.4 off the table, and meant that the best that Johaug and her lawyers could hope for was the one-half-reduction provisions of WADA Code Article 10.5.2.

Even within the 12- to 24-month range that was then applicable, the precedential value of the Čilić decision left Johaug’s lawyers with a tough row to hoe. As the Čilić opinion noted, with regard to objective elements of fault, an athlete should take particular care when it comes to the potential ingestion of substances that are prohibited at all times, as was the case here. The Čilić court also called for a higher duty of care when an athlete takes “a medicine designed for a therapeutic purpose,” on the ground that “medicines are known to have prohibited substances in them.” These facts obviously weigh against Johaug on the facts of her case.

The Čilić decision is potentially more helpful to Johaug when it comes to the subjective element of fault. It lists, for example, language or environmental problems and high levels of stress as mitigating factors, both of which seem favorably applicable to Johaug and her facts.

But the Čilić panel also noted that the objective element “should be foremost” in distinguishing between significant, normal, and light degrees of fault, with the subjective element then “used to move a particular athlete up or down within that category.” That is precisely what Johaug’s panel did; that took her to 16-20 months, and then to precisely the middle of that range, or 18 months, for a “standard” normal degree of fault.

Two final thoughts:

One, even with the exact same initial facts and subsequent legal conclusions, the outcome would have been different three years ago – the Čilić case actually discusses a “normal” fault range of 8-16 months, with a “standard” normal degree of fault meriting a suspension of 12 month. This is because, at the time, a possible sanction for someone in Johaug’s position was 0-24 months, not 12-24 months.

The increased lower end of the range reflects a revision to this part of the WADA Code effective January 1, 2015. Had all this occurred in the leadup to Sochi, a finding of no significant fault would have led to a suspension of not 18 months but rather 12 months, or obviously less than the 13 months that Anti-Doping Norway originally imposed in Johaug’s case. Revisions to laws (or, literally, to the World Anti-Doping Code) often mean that proportionality in sentencing exists synchronically, but not diachronically.

And two, everyone involved in this case – not only Johaug, but also the International Ski Federation that sought to see her suspension increased and the CAS panel that decided the case – agreed that the drugs in Johaug’s body were there inadvertently, that Johaug did not intend to cheat, and that she did not gain any competitive advantage from taking this substance. (para. 206)

And yet, once a finding of no fault was off the table, Johaug was subject to a suspension of at least 12 months, and as much as 24 months. Whether or not this seems like a fair and appropriate outcome, these facts and conclusion illustrate the implications of a strict liability scheme for doping violations.

* * *

Disclaimer: The analysis set forth in this article is intended as general news analysis rather than as specific legal advice. While the author is a licensed attorney and a member of the Bar of the State of Alaska, he gives legal advice only following an initial consultation and the formation of an attorney–client relationship. Anyone seeking legal advice specific to their situation is advised to consult with an attorney practicing in that field.

Gavin Kentch

Gavin Kentch wrote for FasterSkier from 2016–2022. He has a cat named Marit.