BORMIO, Italy— I used to be a ski racer. I trained, all year; I raced, all winter.

But the funny thing is, I became a skier through two programs which placed an emphasis on things like “skiing as a way of life” and “the joy of skiing.” Were we supposed to train hard, ski fast, improve our technique? Yes. But there was a tacit understanding that in order to accomplish these goals, we had to appreciate skiing for what it was: skiing. If we were working only for results, then eventually the love affair would end and we’d be out of the sport.

My old coaches did their jobs well and although it’s been a few years since I would call myself a ski racer, I still seek out skiing wherever and whenever I can find it. I tried moving on. I even tried living in cities where it doesn’t snow. But I couldn’t shake that itch, and just myself spending more and more of my weekends traveling in pursuit of my favorite white, powdery drug: snow. It always makes me feel better.

So, Cascades? Check, so much that my friends got sick of me sleeping on their couch. Arctic circle in November? Check. Pyrenees in the spring sun and French Alps in the spring rain? Check, check.

The natural extension of this quest was summer skiing. And so when I found myself with a four-day weekend, I looked at the map and realized that snow – which I see in my work in the Swiss Alps every day, but not in any skiable form – was not so far away. Just across the Italian border was the small town of Bormio, and behind it the legendary Passo dello Stelvio, one of the first popular summer ski destinations. Skiing in August was possible, and just a train ticket away. Of course, I bought the train ticket.

What is it about summer skiing that has such an allure? It doesn’t matter if you are a backcountry explorer, an alpine racer, or a cross-country enthusiast. When you think of escaping the summer heat of wherever you live, heading into the mountains in your t-shirt, and hopping on your skis, your eyes get a little brighter and your heart beats a little faster.

Even glaciers themselves are magical – living things that grow and shrink and move, and that hold snow when it should be impossible. Beneath a smooth(ish) surface might be a crevasse that could swallow you whole. Far below, rivers run into waterfalls, and even if the glacier appears to be the same size from above, they are constantly melting enough water to feed entire valleys below them. To a New Hampshire girl like me, this is goosebumps stuff.

At work the next day, I told my coworkers about my plan.

“You get to go skiing?” my Swedish friend Sofia said through literally clenched teeth. “Oh my God. I want to go skiing so badly. Skiing in the summer!”

My Austrian co-worker, Günther, describes snow with reverence. He refers to it as “the fifth element,” something on its own distinct from water, and definitely much better. So when I said I was going skiing for the weekend, he was jealous. He had friends coming to visit from Austria to do a long backpacking tour, but his first reaction was, “I almost wish they weren’t coming so I could go skiing instead.”

From that, it became something else.

“Shut up,” he said. “Shut up. Shut up. Shut the f**k up.”

(The three of us actually have a very fun and productive working relationship.)

My coworkers understood perfectly this quest for summer snow. For Günther, the idea of me spending all day on the glacier, skiing until I was too exhausted to move, seemed almost unbearable. Every time we saw someone who asked what our plans were for the long weekend, I’d begin to say, “I’m going to Italy to go sk—“

“Shut up,” he’d interrupt. “Shut the f**k up. I don’t want to think about it!”

From there, he began to console himself by imagining why it wouldn’t be as wonderful as I was boasting. We’d be on some mountain, doing our work, when he’d stop and say something like: “You know the freezing line is 4,000 meters?”

“Yeah.”

“Well there aren’t even any mountains in Italy that are 4,000 meters. How is the snow supposed to be any good? It’s probably going to be really hot and the snow is going to suck.”

“I don’t know,” I’d reply. “It’s pretty high. I mean, I guess it’s not 4,000 meters, but it’s at least 3,000 and I saw some pictures of the Italian national team there last week. It looked pretty gorgeous. It definitely looked like good skiing.”

He would just shake his head.

But he understood.

***

Strangely, when I arrived in Bormio, the people I met didn’t have the same attitude. Whether it was the other guests at the hotel’s breakfast buffet, or the Canadian girl who accosted me in a restaurant after hearing me speak English and insisted on telling me her life story, or the German guy who tried to talk me up as I walked down the cobbled streets to dinner, their reactions were the same: wait, you’re here to ski?

To me, it was obvious. Unlike most places in the world, the opening of the ski resort at Passo dello Stelvio doesn’t signal the start of winter. Far from it. In winter, the pass is so buried by snow that it is closed completely. Only in May, when enough of the snow melts, does the pass open. That signals the start of summer. The first ski school opened here in the 1950s, and they might be the most famous summer ski schools in the world.

(For a nordic perspective, from the pass, it’s under half an hour to Santa Maria Val Mustair, Swiss star Dario Cologna’s hometown. He sometimes trains at Stelvio. The Norwegian team has done a camp here too.)

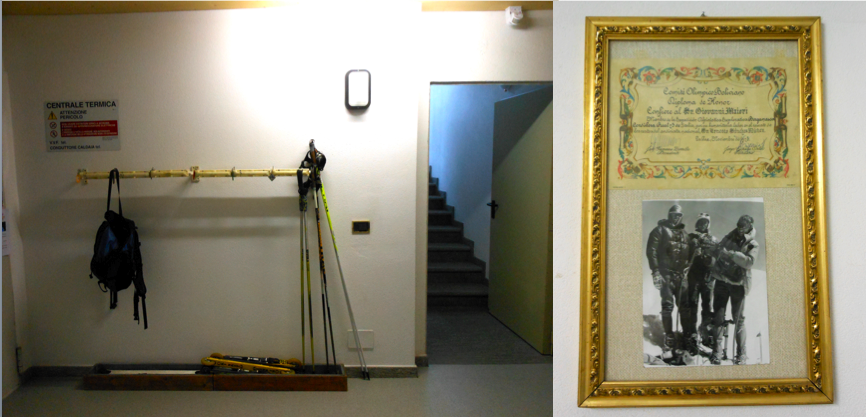

All around Bormio is evidence of a great skiing past. Hotels have trophies, plaques, and photos of the members of their families who were ski champions or who accomplished noteworthy feats of mountaineering in days gone by. The hotel where I am staying is run by the Maiori family; as I unpack my skis, Mr. Maiori’s eyes light up and he tells me that his son, Andrea, is a biathlon champion of Italy, and he thinks that the younger girl, Francesca, will be a good cross country skier.

There are rollerskis in the corner and pair of top-of-the-line OneWay poles.

“A month ago, the cross country skiing at Stelvio was perfect,” Mr. Maiori tells me, kissing his fingers and then releasing them into the air in that typically Italian gesture.

Today, though, my skis are the only ones in the racks that line this basement room. Bormio doesn’t have many ski tourists, at least not at this time of summer. There are plenty of tourists, but they are here either for sightseeing or to ride their bikes up the famous Passo dello Stelvio, with its 30-plus hairpin turns and 1500 meters in elevation gain. Even though that lands them at the bottom of the ski area, most were completely unaware that it was even open for business.

Some of the surprise was justifiable. It’s gets up to 80 degrees during the day here in town, so imagining skiing is pretty tough.

But even after I would describe how at the top of the pass, you take a cable car up to the glacier and then it’s all skiing – they would still be confused. Every single person I talked to in town had the same next question: “so you’re a professional skier or something?”

To them, skiing in the summer was not something you would ever do unless it was part of your job, or unless you were training for something big.

I emphatically disagree with this attitude.

But after a few of these interactions, I begin to wonder: does searching out snow like this mean that I’m crazy?

***

If you don’t have a car, then the way to get from Bormio up to Passo dello Stelvio is by bus. I settled down with the tourists, who were mostly just headed up to take a few pictures, drink a cup of espresso, and then go back down again. The guy sitting behind me talked to himself the whole time as the bus labored around the hairpin turns and through the narrow covered galleries that protect the road from avalanches. I don’t know Italian, but I know that he was crazy.

Passo dello Stelvio is the second-highest pass in Europe, sitting at 9,045 feet. It has some cool history: it is right on the Swiss-Italian border, and right next to “Dreisprachenspitze” or “three-languages peak”, where Italian, German, and Romansch are spoken on different sides. In World War I, Austria even owned a corner of this territory, and Austria and Italy had to make a deal not to fire over the Swiss portion of the land when they were trying to attack each other.

At some point after that, the hotels went up. They are huge buildings that were once stately, but most look like they haven’t had any external upkeep in a while. The names are painted on the outside, along with advertisements for their summer ski schools. The paint is fading and there are a few that appear to be crumbling at the edges. One is closed completely.

(I later went inside one of the functioning hotels, and though it isn’t the lap of luxury, it’s quite a bit nicer on the inside – a perfectly fine place to stay, with food that looked good. The five cars looking lonely in the huge parking lot wouldn’t have suggested as much, though.)

We arrived in a parking lot that was full of ski team vans but no people – everyone was already up on the glacier. After hiking up the stairs of an ugly concrete building, I got my ticket for the day and hopped in the first cable car. I was alone with the operator, and we glided silently over the mixed snow and rock below. As a cross-country skier, I’m not used to having to take this sort of transportation to get to my trails. At the end of the ride we were only at an intermediate station, and switched to a second cable car for the rest of the trip up.

Finally, I walked out of the next decrepit concrete building and onto a porch with a few empty picnic tables. A hike down to through the gravel would bring you to the snow and the first lift; on either side I could see groomed expanses of hills, dotted with orderly arrangements of gates where tiny alpine skiers were weaving in and out.

“Where is the cross country track?” I asked the lift technician.

“Somewhere over there today,” he pointed around the corner of the hillside and shrugged. “It’s open. Open, over around the hill. You can’t see, but over there.”

Then he went back inside. I had to just trust him.

My first idea was to ski up to the area he had been generally pointing to, but as soon as I started it hit me that I was nearing 10,000 feet in elevation, and wearing a backpack. The joy of being on snow for the first few seconds quickly disappeared as I looked up the hill and thought, there is no way I can ski up this. So I labored away until the first crossover trail, where, ashamed, I climbed onto the lift and took it to the top.

From there, I still couldn’t see the nordic trails. Some Norwegian downhillers looked at me and almost visibly scoffed. But I could see that there were two more lifts, so, sticking to the shallow side of the hill, I carved some turns down to the bottom and looked up. There, snaking back and forth in the space between the two lift lines, were some tracks, and I could see a few guys classic skiing. I took one more lift up and was finally able to drop my backpack on the side of the trail and get going.

The alpine “trails” (actually just wide open hillsides) I had negotiated had been crisp white snow, frozen corduroy in some places, slushy ruts in others where too many athletes had practiced the courses set by their coaches. As I began to ski, I encountered something totally different. The trails were dirty – only a narrow white section in the middle of the trail could be called at all pristine. It was unclear whether it had been groomed that morning or not, but my instincts were telling me no. I cringed inwardly for my skis and the amount of dirt they were picking up.

There were just five other skiers, and they were classic skiing, so the trail had not been skied in for skating at all. I found myself laboring again, pushing a V1 on the flat to get through the sluggish snow. With the elevation now almost 11,000 feet, it was hard – really, really hard. I was quickly reduced to skiing in my t-shirt and sweating profusely in the sun. Every once in a while in the middle of the trail there would be a rock sticking up, beginning to melt out the snow around it.

I had envisioned a morning of skiing, then eating a relaxing lunch and reading my book in the sun, followed by an afternoon of more skiing. But I began to panic. What had I gotten myself into? There was no way I could ski in this stuff all day – I was barely sure I could skate for an hour. This was not the winter-in-summer that I had dreamed of.

It was like a real-life version of the old saying: be careful what you wish for, because you just might get it. I had wished for summer skiing, and that’s what I got. Maybe Günther was right. I stuck it out until lunchtime, then hitchhiked back down to Bormio for the afternoon, exhausted.

***

I guess I had been naïve. My expectations were too high. In a recent NPR radio piece, Kikkan Randall called the Eagle glacier in Alaska “not the most glorious conditions to ski in.” If, unlike me, you’re a glacier-skiing pro, you probably know that summer snow isn’t exactly perfect.

But I wasn’t expecting an extra-blue day, either, and those expectations were built on at least a shred of truth. I know what I’ve seen: pictures of snow, the recognizable texture of corduroy. The images from Eagle look far nicer than what I encountered at arguably the most famous summer ski destination in Europe. Even the photos from the Italian team, taken a few days earlier, looked much more inviting.

(I wonder whether the ski area takes greater pains to prepare the tracks when they know their own national team will be there. It doesn’t seem a stretch to imagine. I also wonder whether the nice, crisp snow on the alpine trails is the result of salting or some other preparation that they don’t deem necessary for the ugly stepchild of cross-country skiing.)

Regardless of why I had hoped for more, 24 hours later I had accepted the reality of Stelvio. My illusions and silly childhood dreams had been dashed, but with lower expectations, day two was a lot more enjoyable. I brought classic skis and while traversing and descending the alpine trails to get to my own loop was a lot less fun, once I was out there and got the right wax on my skis, I was really skiing. I no longer felt like the trip was a mistake.

It was a slow slog, but I could stride with good technique and make my way around the zigs and zags without having to take a million rest breaks. Was it just as hot and slushy? Yes. But this was summer skiing that, for at least a day or two, was a real treat. My drug was working, just as it always did: the stress from my working life was melting away, and it was just me there, in the moment, with my skis and the snow and, soon, a sunburn.

Yet I still wondered: is this all there is? Skiing back in forth in parallel, dirt-crusted tracks between whiter slopes where World Juniors racers are laying down run after run of giant slalom training?

Say that I’ve learned nothing from this experience, but I still think there might be more. Maybe it’s not in Italy, maybe it’s somewhere further afield. Or maybe I just missed it in time. But I don’t think that the Stelvio I experienced is the one that earned all the fame.

These aren’t the 1960s; they aren’t the 1990s, either. Stelvio isn’t the mecca it once was. Yes, there are all those junior teams. But if you’re looking for tourists and recreational skiers, you won’t find too many of them. I encountered a group of stoner snowboard bros in the cable car, but that was more or less it.

Twice, I ended up hitchhiking down from the pass to Bormio, and I discussed Stelvio’s fate with my drivers. We all agreed on at least one thing: the valley itself was perfect, amazing. The pass is surrounded by a big national park where there are no Mcmansions, nothing at all except hiking trails and a few farms. My first driver was a mountain runner who had first visited four years ago and couldn’t stop coming back. He and his wife had bought a small house and escaped here from Parma as often as possible.

And Bormio, too, is too perfect to be real. It’s still small, and while it has plenty of tourists, it’s not overrun. It’s a ski town but not a resort town, and there aren’t enough people to drive up the costs of lodging or to spur the construction of luxury hotels. The couture houses don’t have their handbag shops here yet. Instead, you wander narrow, cobblestone streets with red geraniums spilling off of every balcony. You can get enough gelato – of any flavor – to put you in a sugar coma for just two and a half Euros, at a dozen different shops. People are friendly, if seldom on time. The mountains are right there.

So what happened up on the pass?

***

I’m not sure, but there are a few clues. My first driver told me that four years ago, the snow would have been better. There’s been so little in the last few years. I ask – this was a really late spring, so surely this year was better?

His young daughter wonders, wide-eyed, in the back seat.

“Yes, there was a lot of snow quite late,” he says. “But then it got so hot that is just disappeared like that.”

He snaps his fingers.

So, July was great, and maybe August never is. Climate change seems to be a significant problem for places like Stelvio, and there’s less snow than there used to be. If you want to have good snow all summer, you have to get a lot in the winter, and that’s becoming less and less common.

While skiing is gaining popularity across Europe, with the industry growing by 1 percent in 2013 after four years of decline, things aren’t so simple in Italy. The country’s share of the ski tourism market has been dropping, and the Italian economy itself is in its longest recession since World War II. The Financial Times recently referred to the country as “paralysed by political and economic torpor” and “rich in suffering bureaucratic impositions.” Young people are leaving in mass exodus, and family-level purchasing power has fallen to levels not seen since the ’90s. None of this is good for the domestic tourism industry.

Fabio Ghisafi, an Italian who serves as wax tech and women’s coach for the Japanese national team, tells me that the Italian ski team has less and less money.

On my second day hitchhiking, I pick out a couple who are loading two pairs of beautiful wooden downhill skis into a pristine Volvo. They have the sleepy-eyed affluence of Como, and as the wife heads languidly into the Hotel Genziana to use the bathroom before we leave, I chat with the husband. He doesn’t want to admit the last time he was at Stelvio – I get the sense it might have been a decade – but he is astounded at what they saw this time. The lack of snow and skiers, the crumbling infrastructure. The shuttered hotels at the midpoint and at Livrio, the top of the second cable car.

“We were talking about this when we were skiing,” he tells me. “I mean, the old hotels– some of them haven’t been used in years. It’s not a new thing. They should tear them down, because it’s making the mountain ugly.”

I got the sense that this couple would not be back for another trip.

The talk of tearing down the ugly hotels is easy to chalk up to rich snobbery – if you’re used to skiing St. Moritz in winter, then yes, Stelvio would be a shock – but he was right. Passo dello Stelvio used to be a playground not just for athletes, but for families. And of course, it would be great if it could be again. There are several dozen perfect bunny slopes – why aren’t there any kids there now, learning how to turn? Why isn’t there someone serving pizzocheri, the local buckwheat pasta and cheese dish, at the top of the cable car line?

But if it can’t, if climate change and economics and the decline of snow sports is too much to overcome for potential investors, then maybe Stelvio should reverse direction. It would be better to get the buildings that are in use looking a little more presentable, and turn the rest back into, well, mountain. The current shabbiness isn’t doing the area’s tourism industry any favors.

Just as I adjusted my expectations for Stelvio, maybe the ski area should do the same. The dreams it was built on might not be realistic anymore. It’s easy, if sad, to imagine the future of Passo dello Stelvio. People will always ski there, but it might get more and more discouraging to do so.

And that leaves me with only one thing still up in the air: what about my own dreams? Am I the only one who still dreams that dream that Stelvio was built on? Am I 20 years too young for this burning, insatiable desire to ski everywhere, all the time? Somewhere along the way, was I dealt a bad line about whether this is even possible, let alone fun? Does the rest of the ski community dream like me, or am I the lone crazy one?

I’m not sure. But I like to think that one of the things that makes me a lifelong skier is the ability to hold two ideas in my head. The first is the image of a little corner of New Hampshire, whose twisting and climbing trails will always represent my favorite place to ski.

And the second idea is that at any given moment, somewhere in the world, there’s great skiing. If I can’t be back home and if it’s not December through March, then a corner of my mind is occupied wondering where that snow is and whether I can get there.

Most of the time, I can’t. But sometimes opportunities fall into your lap; that’s why you can’t forget about the quest, because then they might slip by unnoticed. Childlike, I hope that the next time I find improbable skiing, it will be magical again.

Chelsea Little

Chelsea Little is FasterSkier's Editor-At-Large. A former racer at Ford Sayre, Dartmouth College and the Craftsbury Green Racing Project, she is a PhD candidate in aquatic ecology in the @Altermatt_lab at Eawag, the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Zurich, Switzerland. You can follow her on twitter @ChelskiLittle.

2 comments

imnxcguy

August 5, 2013 at 11:40 am

Great article, Chelsea. Really enjoyed the story.

Martin Hall

August 5, 2013 at 9:25 pm

It was a nice light read that lead you to the finish—also, cute in your need to see and be on snow—a feeling a lot of us have chased all our lives.

Real skiers are always kids—waiting for those first snow flakes—I can remember how excited I was—-especially when it got to that time of the year—waking up and looking out hoping it had snowed—-thanks.