Take a moment to visualize some iconic head-to-head finishes from recent global championships: Klæbo vs. Bolshunov in the 50 k, Oberstdorf, 2021; Nilsson vs. Johaug in the relay, Seefeld, 2019; Schumacher vs. Terentev in the relay, Lahti, 2019; Diggins vs. history in, well, you know, PyeongChang, 2018.

What do these races have in common, besides drama, high-level skiing, and triumph and tragedy in equal measure? All of them feature a final downhill back into the stadium.

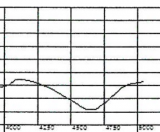

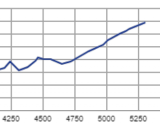

The Zhangjiakou courses that will be used for all distance races, by contrast, starting tonight with the women’s skiathlon, do not have such an approach to the stadium. Instead, here is a course profile of the final kilometer of all the distance courses at Kuyangshu Nordic Center and Biathlon Center in Zhangjiakou, China:

Specifically, note that there is an uphill in this final kilometer. There is a B-Climb with a 14-meter gain, starting roughly 440 meters from the finish, then an effectively flat approach through a hairpin turn and into the finishing strait.

While it is tough to make sweeping statements about what “most” courses “typically” do, a review of homologation certificates and course profiles suggests that Zhangjiakou will present the first global championship (that is, Olympics or World Ski Championships) with a comparable profile for the final kilometer since Sochi in 2014, and the first championship without a downhill into the stadium in at least 11 years. This conclusion is based on a somewhat unscientific survey of the final kilometer of the “main” five-kilometer course at all global championship venues since Holmenkollen in 2011. (Course profiles and methodology may be found at the bottom of this article.)

Here’s a look back, including the final kilometer, at the 30k men’s skiathlon during the PyeongChang Olympics in 2018. Spoiler alert, it was won by Simen Hegstad Krüger, who is currently quarantined after contracting COVID-19 last week, leaving him unable to travel to Beijing to defend his title.

So does this this final uphill matter? If you’ll forgive the lawyer answer, it depends.

On the one hand, if athletes are skiing together in the final kilometer of a race, a course with an uphill approach to the finish may play out differently than one with a downhill approach. Everything else being equal, you might expect a pure climber to have an edge on the final stretch of the Zhangjiakou courses, while this profile could negate the advantage of greater mass that a larger skier would use to gain more speed coming off a final downhill.

On the other hand, the shortest mass-start race at these Games is the 15 k skiathlon (honorable mention: the women’s relay, which is 4 x 5 kilometers and could very well feature a final leg that is much more of a head-to-head 5 k, not to mention that the sprint/team sprint course also has this profile for its final 500 meters). So there exist roughly 14.5 kilometers in which athletes may make a move before this final uphill. More broadly, while this article chose to focus on the final kilometer of each distance course as an arbitrary cutoff for purposes of taking analogous screenshots of course profiles (that is, while clearly the entire course is relevant for how the final kilometer skis, I had to set my parameters somewhere), note that the 800 meters immediately preceding the final Zhangjiakou uphill are nearly all downhill, with a substantial drop of roughly 50 vertical meters, so heavier skiers or better descenders could gain an insurmountable advantage on the flyweight athletes before this climb.

And more broadly still, it may be misleadingly reductive to focus on only the final half-kilometer of a 15-, 30-, or 50-kilometer mass-start race, when we’re talking about the world’s best athletes here, and they will all have a plan to use preceding sections of the course to their advantage, lessening if not obviating the implications of this one final uphill.

One commentator consulted by FasterSkier, Lex Treinen, took an “all of the above” approach when asked for his analysis of the implications of this course profile. Treinen is a former pro skier for APU who reached a national championship podium and multiple SuperTour podia during his racing career, was top American in the 2015 Birkie, and has provided commentary for both domestic and World Cup races, but now describes himself as a “substitute Polar Cubs coach [for the Anchorage Junior Nordic League youth skiing program] and amateur watercolorist.” (Treinen also has a day job as a reporter for Alaska Public Media; disclosure, he was a colleague of FasterSkier reporter Nat Herz until about a month ago.)

“It’s gonna be a tactical finish but not a crapshoot,” Treinen wrote to FasterSkier earlier this week. “There’s something for everyone in the last kilometer – a descent to bunch the group up, a kicker of an uphill for the fitness freaks, and then a grind for the drag racers into the finish chute.

“It’s hard to say what sort of racers it would favor,” Treinen continued. “I think there will be a lot of different ways you’ll see the last 500 meters play out, come-from-behinds, scuffles in the downhill, and grinders who wear out the field in the last stretch.”

So, well, it depends.

Another expert, course designer John Aalberg, acknowledges the differences between the approach to the finish in Zhangjiakou and that in Soldier Hollow, which he also designed: “I was able to design an even better finish for these 2022 courses, with both a long uphill (similar to Hermod’s Hill), an exciting downhill right above the stadium, and a small uphill coming into the stadium (the high speed coming into the Soldier Hollow stadium is not optimal),” Aalberg wrote to FasterSkier. Aalberg also described the final downhill in Zhangjiakou as featuring a “‘velodrome’ downhill corner.”

Bottom line – and apologies for the joyful indeterminacy here – these courses have never hosted a FIS race before; no one knows for sure how they will ski under race conditions. Again, it depends. But as a spectator watching at home, you should get ready for two weeks’ worth of athletes coming off a final uphill into the stadium. And if you’ve ever raced at Birch Hill in Fairbanks (19-meter climb starting 360 meters out), Government Peak in Palmer (19-meter climb starting 270 meters out), or Craftsbury in Vermont (17-meter climb starting 730 meters out), brace yourself for some flashbacks.

Methodology and footnotes

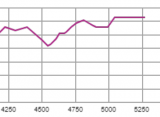

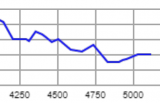

Immediately below are thumbnails of the final kilometer of the 5-kilometer distance course for all global championships since Holmenkollen in 2011. Below that are comparable thumbnails from all domestic championship venues (U.S. Nationals or Spring Series) from this country in the past decade that have homologation certificates currently available. All images are screenshots from the course profile contained in the official homologation certificate, which may be found here. They have been arranged in a wholly holistic manner, according to my sense of which ones would ski most like the Zhangjiakou distance course, sorted by descending order of similarity. Your sense of this may certainly differ.

This is an unscientific endeavor that is more art than science. Indeed, note that each venue has multiple different homologated courses; a 10-kilometer race may be three laps of a 3.3 k course, for example, while a 50-kilometer race is often six laps of an 8.3 k course, neither of which uses the 5 k course at all. I chose the 5 k course distance as a common denominator that all venues in this survey have. I think it is likely that most distance courses will typically have the same final-kilometer approach to the stadium, no matter the overall distance of the course, but this is not always the case, cf. the mass start vs. interval start 5 k homologated courses at Birch Hill in Fairbanks, which follow different routes to the same finish line in the same stadium at the same venue for two courses of the same length, and so have different elevation profiles.

I also acknowledge that the homologation certificates currently available may differ from the course used at the time of a given championship. Historical homologation certificates are not generally available on the FIS site. Again, these are presented as examples for comparison, not as gospel truth.

As one final caveat, I am painfully aware of the risk of confirmation bias here. I train and race in Alaska… and I ranked a Fairbanks course first among domestic courses. That’s convenient. (I really think it’s a tossup between Birch Hill and Craftsbury South; I slotted the Birch Hill mass start course ahead because the final uphill there starts closer to the finish, but reasonable people may clearly differ.) I have raced at one European venue in my life… and would you look at that, Beitostølen has a 15-meter climb back to the stadium, better list it as an honorable mention course.

Bottom line, I would be very open to being told why your home course is in fact a better analog for Zhangjiakou; there are hundreds of courses in the global homologation database, and I did not survey most of them. Please take this article as an illustrative sampling of what’s out there rather than as a comprehensive roundup, and feel free to suggest better matches in the comments. And enjoy the races.

Global championship courses

Zhangjiakou (2022 OWG)

Sochi 5 k left (2014 OWG)

Holmenkollen (2011 WSC)

Oberstdorf (2021 WSC)

Seefeld (2019 WSC)

Pyeongchang (2018 OWG)

Val di Fiemme (2013 WSC)

Lahti blue (2017 WSC)

Falun blue (2015 WSC)

Falun red (2015 WSC)

Lahti red (2017 WSC)

Domestic championship courses

Zhangjiakou (2022 OWG)

Birch Hill 5k mass start

Craftsbury 5k south

Birch Hill 5k interval start

Houghton 5k B

Kincaid JNs 5k

Soldier Hollow Olympic 5k

Sun Valley 5k

Truckee 5k B

Sun Valley 5k

Truckee 5k A

Honorable mention

Zhangjiakou

Rikert Nordic Center, Vermont (hat tip Bill McKibben)

Ruka, Finland

Beitostølen, Norway

Government Peak Recreation Area, Palmer, Alaska

Related reading:

The Enigma of Zhangjiakou and the Kuyangshu Nordic Center (February 2022)

Olympics Preview: What We Know About the Courses and Venue (January 2022)

Gavin Kentch

Gavin Kentch wrote for FasterSkier from 2016–2022. He has a cat named Marit.