“You’re skiing along, and you look up at the green of the pines and look down and see golden tamarack needles peeking out of the Wisconsin snow, and you find yourself gliding along thinking, ‘my gosh, how lucky can one guy get…and Go Packers too!” – Grandpa Theyerl, Wisconsinite, Birchlegger.

The American Birkebeiner turns 50 years old this weekend. And although it didn’t ask for it, I’m doing some existential rumination on its behalf.

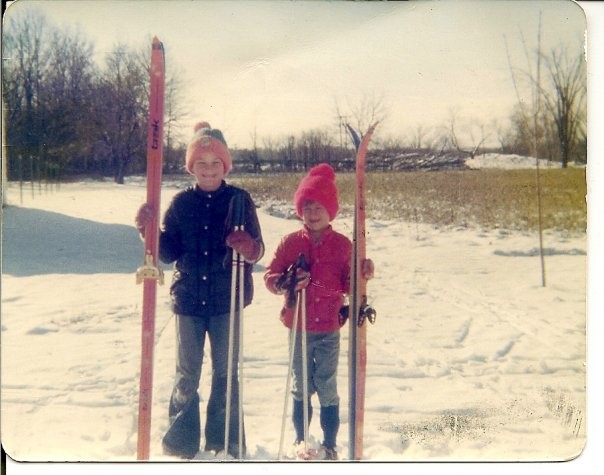

At 26 years old, I’ve only been around for half of the history of the “Birkie.” I was born in Wisconsin, and born into a family whose name has appeared in the Birch Scroll for 45 of the Birkie’s 50 years. Somewhere out there amongst those forested knolls, the Birkie became intwined in my family tree. The simple equation: for a half-century the Birkie has been the quintessential American ski race, and over the same span, it’s been my quintessential family experience. The Birkie is all about the ties that bind: a physical exercise with ontological overtones. The yearly ritual day skiing 50 kilometers from Cable to Hayward has thrown muskie-sized ripples into our lives every other day of the year, and subsequently plotted the course of our collective life over generations. I know us Theyerls aren’t alone in that; we’re joined by thousands of people for whom that fact is the same.

There are two kinds of dreams: aspirational and retrospective—the Birkie has been both. The aspirational dream looks into the future and deciding what you want to see there. That sort of dream was the Birkie of Tony Wise, the ebullient Northwoods businessman who planed to give his hometown an economic engine, and a way to spin a mythology out of snow, pines, and skinny skis. The other type of the dream is the one you find in retrospect; the momentary circumstances and connections that point towards something that feels like home. That’s been my Birkie. I’ve had a lot of great skis in my life, but the best great skis have all been on the Birkie trail. I’ve had a lot of good fortune in my life—making a living in this sport, growing up among the Northwoods of Wisconsin, my parents meeting and starting a family—but so much of that luck began with my Grandpa signing up for the American Birkebeiner 45 years ago.

Tony Wise, Telemark, and the Birkie Idea

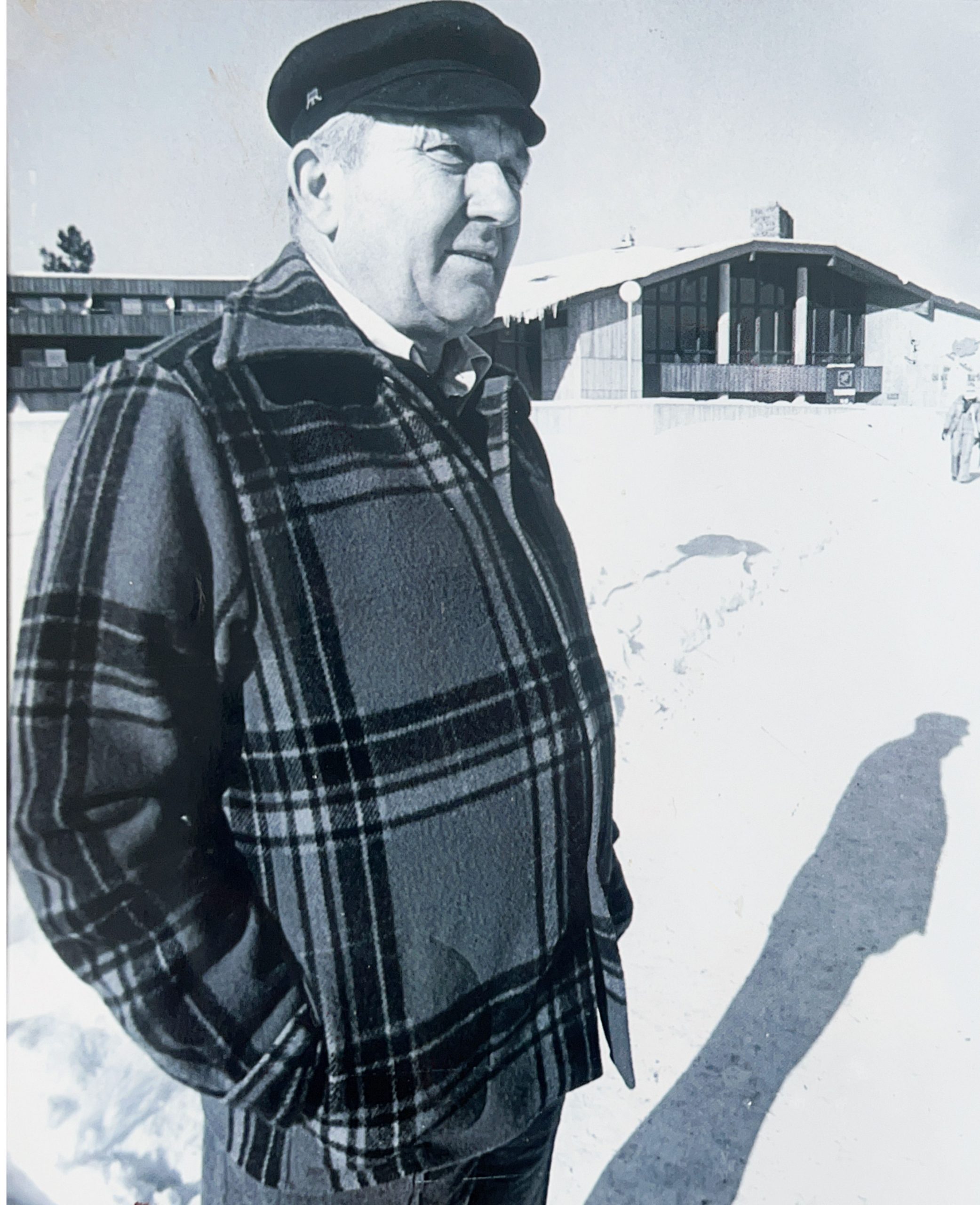

By the time he dreamed up the American Birkebeiner in 1973, Tony Wise had already earned what those back home in Wisconsin, with characteristic Midwestern understatement, have deemed a character. “The brains, brawn, inspiration, energy source, and grand imagination behind [Telemark], a bulky excitable fellow who talks with the chattering speed of a machine gun and apparently thinks the same way,” as a profile on Wise in Ski Magazine put it in 1977. The title of “character” acts as shorthand for a kind of dual spirit inspired by the geography of the Northwoods, its endless pines, countless lakes, and the frigid omnipresence of Lake Superior. This vast region beckons one to dream outstretched dreams.

Wise built his Telemark Resort while living in the same Hayward tar-paper shack in which he’d lived his entire life. His 1995 obituary in the Star Trib (The Minneapolis Star Tribune) would conclude that Wise “built Telemark from a dream, and it did what he said it would do. It brought life and vibrancy and entertainment stars and international athletes and development to what had been a depressed area of Wisconsin.” The lede on the same article also declared “Wise’s bank account showed $0.00 when he died Thursday.” Tony Wise, in life, emptied the tank.

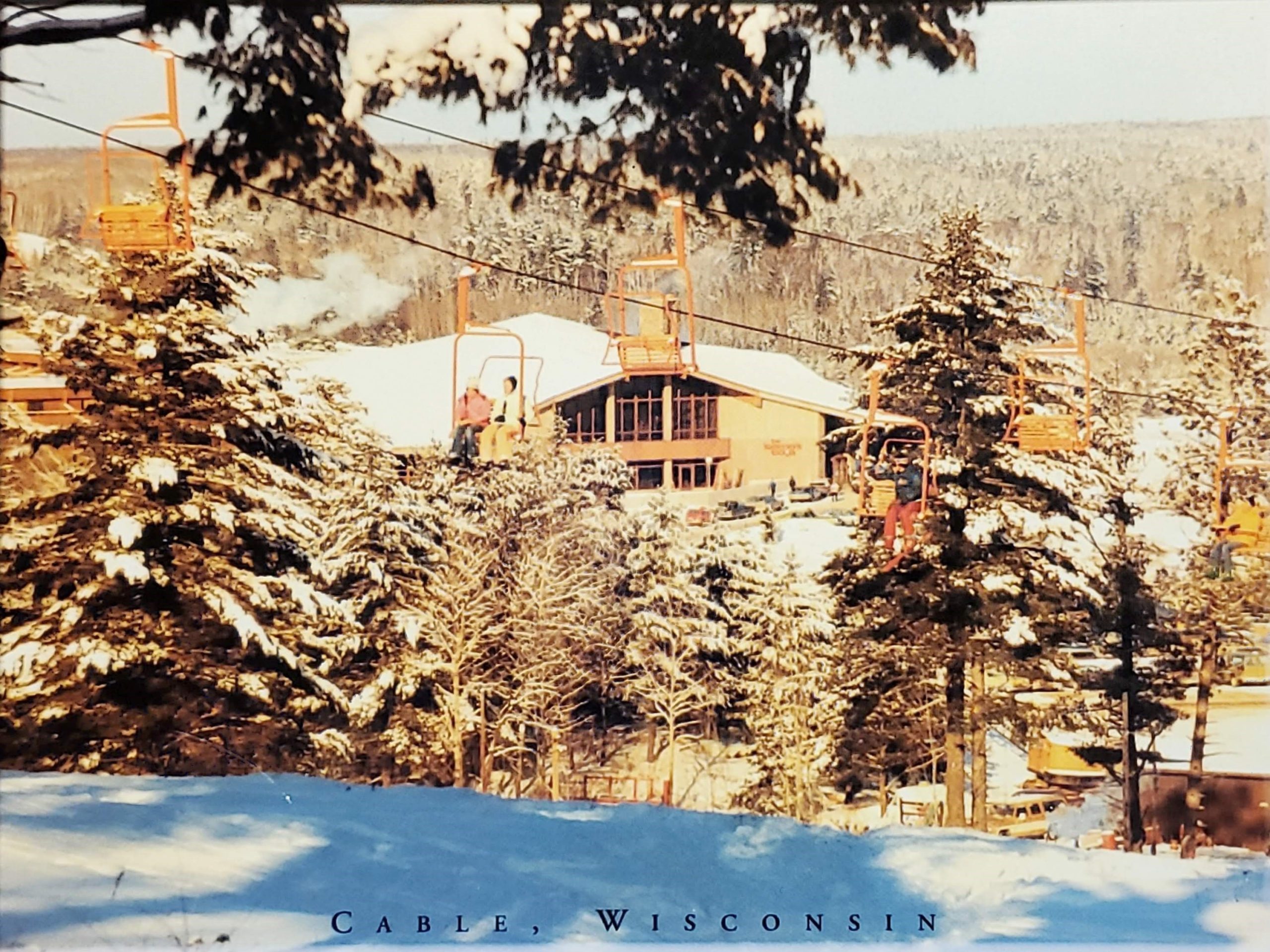

Wise had returned from his post as a tank commander during World War II and founded the ski resort on a 300-foot vertical run with a nothing more than a surplus Jeep engine. Telemark had opened up a new economic era in a Wisconsin Northwoods that had been reeling from the collapse of its lumber industry, providing year-round tourism dollars and jobs to an entire community.

The choice by Wise to pivot away from the downhill ski business in 1973 appears shrewd in retrospect. He had just built his Telemark Lodge, but could also see the limitations of what he was working with in Wisconsin. Airfare to the American West—where old mining towns had took on second lives as ski resorts by simply putting up a lift on the nearest mountain with a 3,000 foot run—was beginning to become feasible for the middle-class. The downhill business was doomed in the Midwest; Wise started to look to other options.

The dense thickets of the North Woods mask an endlessly undulating set of kettles and moraines, left from the last retreat of the Wisconsin glaciation 10,000 years ago. A cross-country ski race would help bring people in on the secret; in 1973, Wise stitched together a path of snowmobile trails, old logging cuts, and hunting footpaths from the Lumberjack Bowl in Hayward to the base area of the Telemark Lodge in Hayward: 55 kilometers. For a name, he leaned into the Norwegian heritage present in the area—“Telemark”—taking legendary story of the Birkebeiners from the Norwegians, and dubbing his event the American Birkebeiner.

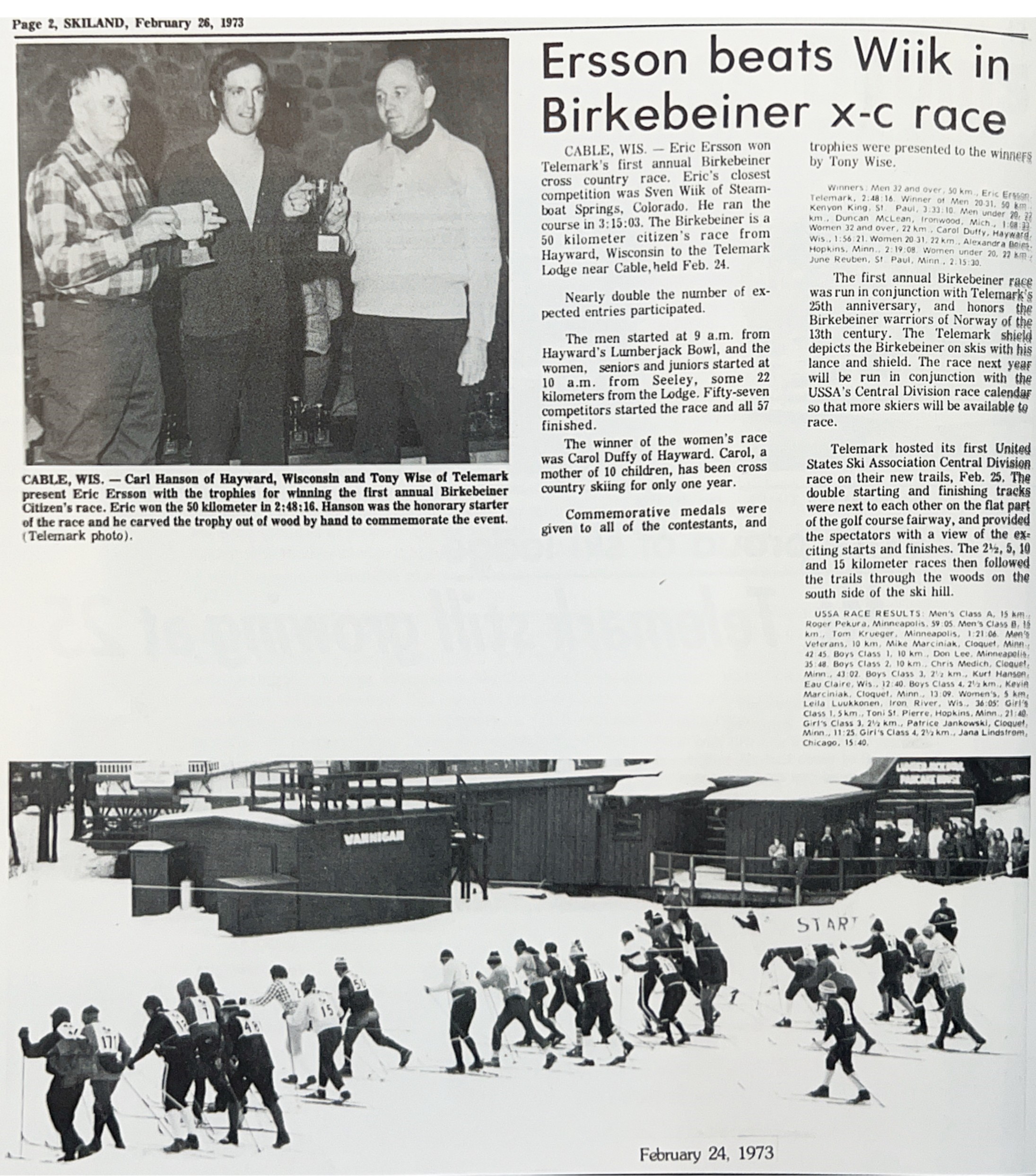

The first running of the American Birkebeiner took place on February 24, 1973. Fifty-seven racers competing across two events. Thirty-four men and one woman, Jacque Lindskoog, completed the entire 50 kilometer course. Eric Ersson, a Swedish skier Wise had enlisted to add to the Scandinavian heritage aspect (he was doing this a lot in the early years), beat out the legendary Swedish-American ski coach Sven Wiik. Another nineteen competitors completed a half-distance course that was won by Hayward local Carol Duffy. Starting in the mid-way outpost of Seeley, this proto-event would become the Korteloppet, the Birkie’s half-distance cousin,

Humble beginnings, but the architecture for what the Birkie is today was all there in its inaugural year: the point-to-point course through the county forests of both Sawyer County and Bayfield County, the name, the perfectly perched late February date making the Birkie the last true gasp of winter before hopes of spring could start to bubble forth among even the most winter-loving souls.

Most importantly was the wide path through cross-country skiing that the first Birkie blazed. In 1973, it didn’t take many people to represent the whole of the American ski community; in truth, the sport was probably in its lowest moment of the last century in the United States. American skiing may have only been three years away from its competitive high-water mark for the next 50 years with Bill Koch’s 1976 Olympic medal at the Innsbruck games. But Koch came from a separate, more-focused, tradition of cross-country skiing that had taken shape in the prep schools and liberal art colleges of New England with a small group that included Koch, Marty Hall, John Caldwell, Martha Rockwell, Alison Owen-Bradley and Rob Kiesel, among others. An older, more populist tradition of nordic skiing in America—having started out among the Scandinavian miners, farmers, and lumberjacks—was already fading out. The grand wooden ski jumps (the more popular form of nordic skiing at the time) that had once been the preferred after-church Sunday entertainment option before the Minnesota Vikings started playing football in 1961 were starting to rot and be torn down from Chester Bowl in Duluth to Theodore Wirth Park in Minneapolis. Numbers in the Minnesota High School Ski League, long the greatest holder of young ski talent in the country, were diminishing.

Founders

The group that started that first Birkie—the now-famous red-bib-wearing “Founders”—turned around the popular participation in cross-country skiing and helped found the ski community we know today. The Birkie revolution was a quiet one, and one inpsired by even more humble actors. Most were local Wisconsinites and Minnesotans who had found their way to cross-country skiing by accident or by heritage. They went on to build the Birkie’s legend by simply expressing their love for skiing.

The echoes of the Founders may be quiet, but those echoes persist. Ernie St. Germaine, a local Wisconsin schoolteacher and tribal chief for the Lac du Flambeau band of the Ojibwe that as of writing is the only person to have completed every edition of the American Birkebeiner. St. Germaine ought to—and I believe would prefer to—always have his childhood Dave Langraff accompany him in his telling of how they did the first event on a whim, and then saw it change their lives for good. Langraff was as radiant a skier as you’d ever find out on a trail, and my few childhood memories of him are the joy he exhibited on skis. That joy comes back every time I ski the Hickory Ridge trails he helped cut outside of his hometown of Bloomer, Wisconsin, where there’s “more lakes than kilometers to ski!” and every sharp jutting corner and fast-running downhill re-asserts a love that resonates down the years.

John Kotar hung up the skis a decade ago and since has helped shepherd the Birkie into a new era of growth as a member of its Board of Directors. There was also Karl Andresen, a Geography Professor in my hometown of Eau Claire, Wisconsin who founded the Eau Claire Ski Striders. Andresen played a kind of Midwestern Falstaff for all that was good about the sport of nordic skiing, regaling us with tales of this Birkie race and the little features of it that had taken on their own mythos: the Power Lines, the Fire Tower, “Double-OO.”

The Founders planted the roots of a tree that’s grown with every new person that has participated in the Birkie over the years, and spawned skiing in the United States today.

Gathering ‘Round for Winter Vespers

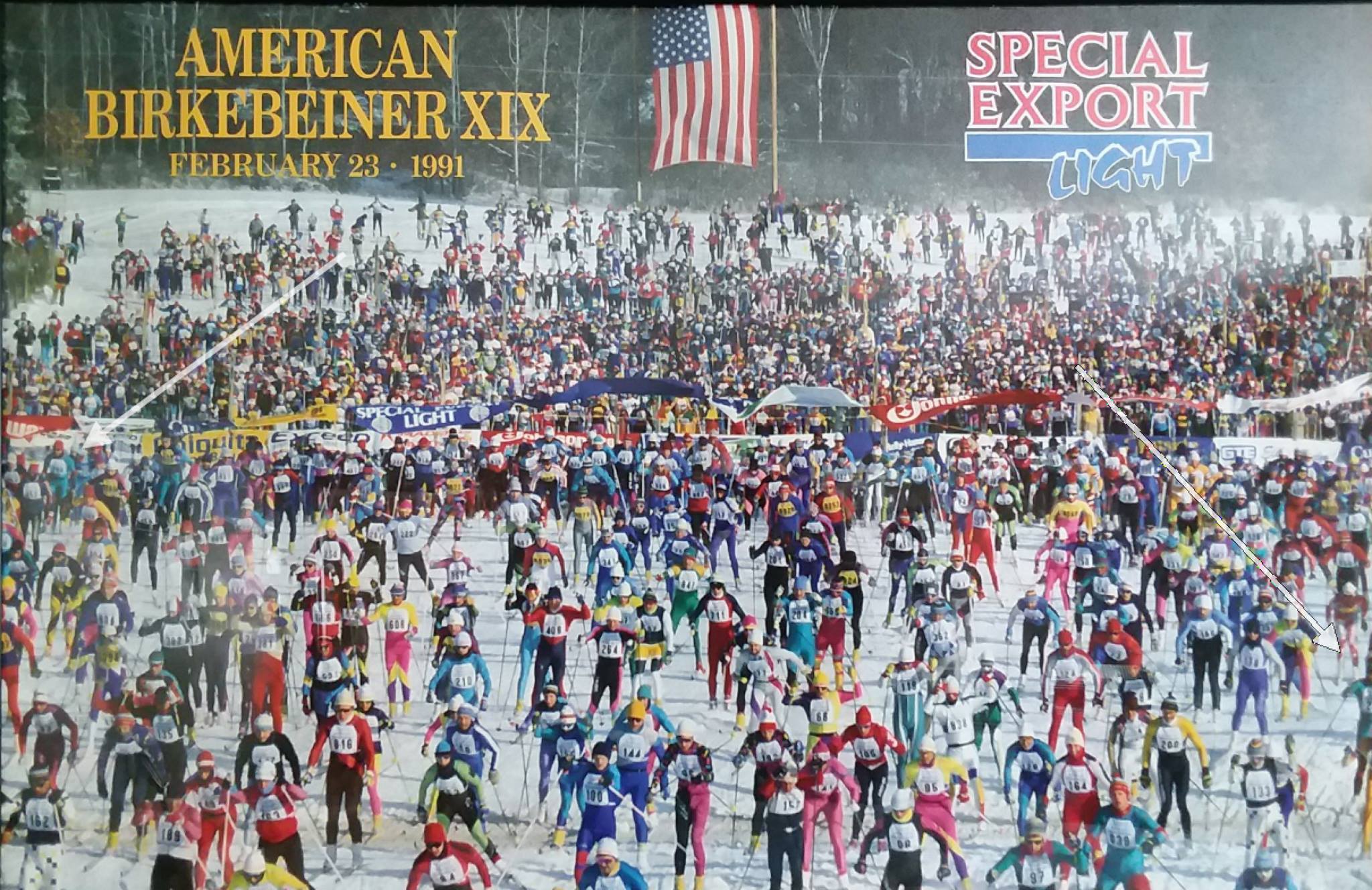

The Birkie was an idea with true intentions: to allow its participants to discover qualities within themselves through the medium of skiing. By the fourth Birkie in 1977—the one my Grandfather first hopped in—the Birkie field had grown from 57 to 2,000 racers. Twenty years in, the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation (ABSF), noticed that there was a unique staying power to the Birkie. A growing group was had been back year-after-year, through the massive changes in a human life that come about over decades. The observation resulted in the establishment of the Birchleggers club, who’s membership requirement is twenty Birkie’s completed, and who are easily identifiable on trail by their purple bib (then gold, after 30 Birkies, then red, after 35).

The Birchleggers now number in the hundreds. Within their ranks, there are just as many Birkie stories, and many of them key in on one particular metaphysical quality. Though the Birkie race course has remained a relative constant for them, the lived experiences they bring to the race each year, and the experiences lived during the race each year, continue to offer something close to constant discovery.

My father—Ted Theyerl—who is 34 Birkies in at the time of this writing, signed up for his first Birkie as soon as he turned 18 in 1986. He earned an elite wave placement based off placing second in the Korteloppet the previous year. He completed the race that year skating, but still had kick wax underfoot because “no one could believe you could climb without it!” From there, through college, and well into his days as the fittest coach on my little league baseball roster, he’d consistently place in the top two-hundred, earning a bid in the Birkie’s elite wave the next year. One year in the early 1990s, he was out early-season training near his home in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, fell, and fractured his leg. In need of rehabilitation to keep his Birkie total on track, he turned to a Physical Therapist name Denise. They hit it off, got married, and here I am, their son, recounting the story.

When Dad finally left the elite wave, it was in another crash. In 2010, my mother and I were mingling in the crowd at Angler’s after my first Korteloppet, when the wave of Birchlegger elite wave finishers that my Dad usually finished with started to filter into the scene telling us that Dad had taken a hard fall. Dad had separated his shoulder near the unofficial half-way point at County “OO” in Seeley.” He stopped off at the aid station, discarded a broken pole, took up a sling, and proceeded to skate towards Hayward. “I remember thinking, well, this will be different,” he recounted. “I don’t have to sprint across the Lake now!”

Eventually, we found him wandering on Main St. in Hayward among the thousands of people he’d smiled, greeted, and had conversations with throughout his long, slow, one-pole skate to Hayward. To this day, he remembers that as one of his most enjoyable Birkies where the miles lay long and thick with connections to other skiers behind him. Dad eventually slipped out of the elite wave permanently, and then took up skiing with my brother, or sister, as they started to forge their own Birkie journeys.

Admittedly, I haven’t pulled my weight in the family Birkie legacy, having spent most of my adult life far-flung from the Northwoods of Wisconsin and with only two American Birkebeiner finishers to my name. There’s irony in that: because of the Birkie, I’m now in a spot where I can’t do the Birkie, and will be spending this year’s Birkie Saturday at a wax bench in Colorado coaching the Crested Butte Nordic Team. It’s a circumstance I count as a blessing, not unlike the example of my aunt, Tracey Cote (nee Theyerl), who left the Birkie twenty-six years ago to take up the helm of the Colby College Ski Team. She’s been spending the last weekend in February on the collegiate carnival circuit ever since. Time and distance haven’t diminished my love of a race that has directed where I’ve gone and who I’ve known in life.

I can still evoke the feeling I had during my first Korteloppet when I turned the corner three kilometers into the race. I saw the Power Lines stretching out before me, laden with zig-zagging masses of skiers and supporters. I felt like I’d arrived at a familiar haunt. Perhaps because I’d spent the first 13 years of my life envisioning what that moment would be like, I reached that rare state where you truly can appreciate the miracle of every lived moment. I’ve been in a coasting of sorts ever since that, always getting somewhere near that state out on the Birkie trail, trying to suck the marrow out of every particular instance and experience. The other moment that sticks out to me during that first Korteloppet was biding my time in the line up one of the first big hills when a man wearing one of the red “Spirit of 35” Birkie bibs pulled up next to me, and shouted, “Ben!” I looked over, and got an introduction, “I’m Jim O’Connell, your Grandpa and I used to be out here together,” and in an instant, the Birkie Trail seemed to stretch before me to a different, looser, sense of time construed not around some linear march through life, but instead by the connections you make in it.

I may not be the only one who experiences epiphanies out on the Birkie trail; from the evidence I can gather, those epiphanies are out there for nearly everyone, just as unique as the racers experiencing them. I choose to believe there’s a reason there have been so-many repeat winners, that there’s a logic behind why Caitlin Gregg, Matt Liebsch, David Norris, Alayna Sonneysn and those others who come back to compete for the top step of the Birkie podium every year. I choose to believe it’s probably along the same lines as those who are pulling over to breathe in the pines, and thank the volunteers, and make their way to Hayward from Wave 8, and 9 and 10.

The real miracle of the Birkie is in the repeating ritual: popping through old sawmill towns, gaining that first view of the Namekogan river on the drive to Hayward, the bridge welcoming you into Birkie-land has always read “SPOONER BLOWS” in your rearview mirror. The “Viking Warriors” in full regalia still make their way to Hayward. The Sawmill Saloon in Seeley with its Birkie Bash, and seeing snowmobilers and Birkie champions, alike, gain equal purchase over a fish fry and a good ol’ can of Leinie’s O.’

Through the many seasons of our lives, the Birkie has become communion: a gathering ‘round for vespers each winter. In skiing that fifty kilometers, we’re reminded that the winter can be warm, it can make you shed a few layers, and that the harsh winter cold is no match for the warmth that human souls, pointed together in the same direction, can provide. That’s as close to a source as I can identiry for that “Birkie Fever” that’s run through skiers for fifty years. The Birkie: a dream dreamed, a dream realized, and a dream that skis on.

Ben Theyerl

Ben Theyerl was born into a family now three-generations into nordic ski racing in the US. He grew up skiing for Chippewa Valley Nordic in his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, before spending four years racing for Colby College in Maine. He currently mixes writing and skiing while based out of Crested Butte, CO, where he coaches the best group of high schoolers one could hope to find.