US Ski & Snowboard recently hosted a course titled “Medical Emergencies in Skiing and Snowboarding”, which is required training for all physical therapists and athletic trainers working with the team during competitions. As the name would imply, we learned about emergency management of acute injuries: application of cervical collars, tourniquets, back boards, distraction splints, and plenty of other nasty scenarios we hope to never see.

Thankfully, cross country skiing tends to be lower risk when it comes to traumas and medical emergencies. Typical of an endurance sport, our injuries are more self-induced from the volume and intensity of training. Instead of blown out knees and broken bones, we contend with tendinopathies, muscle strains, and joint pains. For better or worse, these ailments are quite common, and we’re pretty good about diagnosing and treating them. That might not be the case with a condition called Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome (CECS), a painful condition most often affecting the lower leg. It’s common among Nordic skiers, it’s painful enough to seriously disrupt training, and it’s often difficult to diagnose and treat. This article attempts to investigate the condition, and to offer some advice to those suffering from it.

C.E.C.S.

Chronic. It occurs repeatedly and/or persists over time (not the result of a trauma).

Exertional. It happens with effort. This is one of the hallmarks of the condition: symptoms are present with exercise, often only at higher intensities, but tend to subside fairly quickly with rest.

Compartment. Throughout our bodies we have connective tissue called fascia. I think of it as Saran Wrap. It’s thin, pliable, and has a small amount of elasticity. Our organs are packaged in fascia. Muscles are encased in fascia. The typical physiological explanation for fascia is that it creates “compartments” to reduce the spread of infections or pathogens. (From a musculoskeletal perspective, fascia may play a large role in how our muscles, tendons, and joints interact.)

Syndrome. A group of symptoms that occur together. Generally, not a good thing.

CECS occurs when exercise causes the muscles within a fascial compartment to become swollen and enlarged to the point of exceeding the space within the compartment. This leads to decreased blood (therefore decreased oxygen supply to the muscles) and ultimately pain, numbness, and/or weakness.

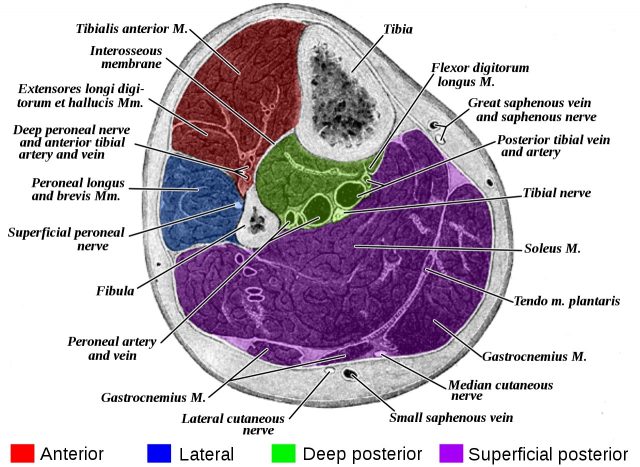

CECS almost exclusively affects the lower leg, which has four compartments.

- The anterior compartment contains muscles of ankle dorsiflexion and stability, primarily the tibialis anterior.

- The muscles of the lateral compartment provide dynamic stability at the ankle.

- There are two posterior compartments: the superficial compartment with ankle plantar flexors and the deep compartment containing muscles that stabilize the ankle and foot.

The mechanics of CECS is a simple matter of too much stuff in too little space. The more that muscles work, the more oxygen they need. The body obliges by increasing the heart rate, pumping more blood, and delivering more oxygen. This causes the muscles to swell and take up more space. While the fascia has some elasticity and ability to stretch, it does become quite confining and won’t let the muscles expand any further. This causes pressure to build within the compartment.

So far, this is all a normal physiological response. But, if the incoming blood flow continues at a higher rate than the outgoing flow, the pressure will continue to increase. When the compartment pressure exceeds that of the blood vessels, blood flow becomes restricted. The muscles become starved for oxygen and will get very pissed off. Pain is the body’s response, yelling at you so you’ll stop what you’re doing and leave the poor muscles alone.

Traits of CECS

Pain is the most common complaint with CECS. It is sometimes accompanied by numbness or sense of weakness. Along with pain, there is often a description of tightness or cramping. As previously mentioned, symptoms arise only with exertion and subside quickly – often within only a few minutes of rest. Symptoms arise only with exertion and subside quickly–often within a few minutes of rest. This is a key trait of CECS.

Location of pain is commonly bilateral and often broad–it takes a whole hand instead of a finger to point to the pain. However, it is almost always within the anatomical borders of the compartment. (This does get more vague when multiple compartments are symptomatic, especially the combination of anterior and lateral.)

Symptoms of CECS are typically very hard to reproduce without the exertion of the offending sport. This is a clinician’s nightmare as we glean a considerable amount of information when our tests reproduce the patient’s pain.

Taken together, these traits are what will most readily differentiate CECS from other chronic musculoskeletal issues like tendinopathies, muscle strains, or joint pathologies: symptoms subside quickly with rest, are diffuse, and are not reproduced during a physical exam.

Diagnosis

The gold standard is an exercise test using an intra-compartment pressure monitor. It’s basically a syringe needle attached to an air pressure gauge. The protocol is to take baseline measurements at rest and then again after exertion. The pressures are compared using the Pedowitz criteria: “1) a preexercise pressure greater than or equal to 15 mm Hg, 2) a 1 minute postexercise pressure of greater than or equal to 30 mm Hg, or 3) a 5 minute postexercise pressure greater than or equal to 20 mm Hg.” This essentially means 1) your resting pressure is really high, 2) your pressure under exertion is really, really high, or 3) your intra-compartment pressure is not decreasing normally with rest.

Treatment

Conservative treatment is frequently not very effective but certainly worth exploring, especially if you are trying to make it through competition season. Massage and taping are the most common interventions that have potential for at least short term improvement (if a bit of tape lets you race without pain, that’s a win!). There may be more substance behind altering the movement pattern responsible for CECS in the first place: for example, this study found very positive results by making changes to the subjects’ running gait and foot-strike pattern.

Unfortunately, we are not very good at treating CECS without a scalpel. Surgery is by fasciotomy. Oversimplified, this is a procedure where the fascia is cut to create more space within the compartment. For most surgeons, a positive on the Pedowitz criteria is a prerequisite; however, they will also consider the compartments affected and the severity and duration of symptoms. While not perfect, surgical outcomes tend to be pretty good. A study of elite French skiers with CECS observed that 94% became asymptomatic and almost 90% returned to competition after fasciotomy surgery.

Ski-Related CECS

The article just referenced found the prevalence of CECS to be 6.1% among the elite, national team skiers they studied. It was slightly higher amongst biathletes and slightly lower for cross-country skiers. Symptoms were much more common with skate vs classic skiing techniques, and the anterior compartment was the most commonly affected.

The anterior compartment and skating

Recall that the anterior compartment houses muscles that generate ankle dorsiflexion, in other words, the muscles that lift the foot and toes toward the shin. When we skate, we lift the kick ski off of the snow before swinging it back into position for gliding–a motion that activates the dorsiflexors. But these anterior compartment muscles, especially tibialis anterior, are also ankle stabilizers. When we balance on one leg, the tibialis anterior is co-contracting with the soleus and gastrocnemius to maintain stability. So, it is also very busy during the glide phase so it is getting very little rest. In contrast, with classic technique the kick ski stays mostly on the snow and is brought forward action at the hip vs ankle. Meanwhile, the glide phase balance demand is generally lower.

Too much tibialis anterior? That was the finding of this study that looked at muscle activation during skate skiing. In comparing elite skiers with CECS to their asymptomatic teammates, they saw greater tibialis anterior muscle activation in the swing phase (active dorsiflexion) but even more so in the glide phase (dynamic balance).

The swing vs glide question was also inadvertently investigated in this novel study from way back in 1992 when skate technique was emerging. And, unfortunately, so too was CECS. The authors measured intra-compartment pressures after subjects skated with both skate and classic skis. While they found slightly higher pressures with classic skis, the results were not deemed statistically significant. This would seem to demonstrate that the increased load on the dorsiflexors from swinging a longer, heavier ski did not make much difference.

The Takeaways

CECS is common enough amongst at least competitive cross-country skiers that it should not be considered an outlier diagnosis when a skier complains of lower leg pain.

Diagnosis can be tricky, and often misleading, but relatively clear with intra-compartment pressure testing. (Clinical interjection: The testing must be done with the offending sport/activity to be accurate. Most physicians will be accustomed to patients who are symptomatic with running so the common test is running on treadmill. If a skier is only symptomatic with skate skiing, a running test is likely to return a false negative. They need to reproduce their symptoms; therefore, they need to skate ski/roller ski for the test.)

Anterior > lateral > posterior compartments. Skate > classic. Maybe symptomatic with other exercise and training but maybe not.

According to the current research, those who meet the compartment pressure criteria will likely be unsuccessful with conservative treatment and ultimately require surgery, though it should be expected that most surgeons will want to see a failed trial of PT before they operate. However, there are some tactics, from taping to training modifications, that might help to at least decrease symptoms and are very much worth exploring, especially in the short term if trying to salvage a competitive season.

The glide phase is likely the most problematic. This would seem to indicate a technique and balance issue. This is also where those of us who do not wield scalpels might make a difference in both prevention and treatment (even if the skier has had surgery). I, for one, consider the ability to demonstrate appropriate balance in ski-specific postures a prerequisite for effective skiing and recommend single leg stability exercises to all skiers, independent of CECS treatment. To paraphrase a recent interview with Matt Whitcomb, head coach of the US Ski Team: “[A]ll great technique starts with the ability to use our feet well. And for anyone that has a hard time being stable on their feet, it’s going to be very difficult to ski well in the rest of the body.” If technique changes can improve symptoms in runners with CECS, as noted above, perhaps the potential exists for skiers as well.

Ultimately, CECS is complex and often quite pernicious. Neither surgeon nor physical therapist has a magic sword to slay the dragon. However, if athletes, coaches, and medical providers work together as a team, they look to have a much better chance of taming it.

Ned Dowling

Ned lives in Salt Lake City, UT where his motto has become, “Came for the powder skiing, stayed for the Nordic.” He is a Physical Therapist at the University of Utah and a member of the US Ski Team medical pool. He can be contacted at ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.