Building a Better Skier is a multi-part series born from the inquisitive mind of a physical therapist and late-blooming Nordic skier. (You can find the intro to the series here.) The objective is to explore how biomechanics and movement patterns affect skiing technique, and more importantly how you can apply these concepts to improve your skiing. To cover this topic thoroughly would likely require a hefty book, so apologies in advance if these articles lack depth or specificity. Please feel free to email the author with any questions: ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.

Posture is loosely defined as our body’s position or the way we hold ourselves. We tend to think of posture only in a static form like sitting or standing. But posture can be observed with dynamic activities like running, cycling, or skiing. Truly, we can talk about posture with anything the human body encounters.

The primary influencers of posture are mobility and awareness. (It could be argued that strength plays a role in posture, and that is true for many sedentary people, but the readers of FasterSkier are far from sedentary.)

The mobility or range of motion that is readily available through joints and soft tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament, and fascia) will affect our posture simply because we will always default to moving through the path of least resistance. If a joint is stiff, we will find a way to move around it. If a muscle is tight, it changes the position and efficiency of its associated joint. But also, if the ligaments around a joint have become loose like with recurrent ankle sprains, the muscles and associated tendons will have to work harder to maintain stability. Like with skiing technique, and posture in general, mobility occurs along a bandwidth. There is no single optimal measure, but there is a range that if exceeded on either end will lead to inefficiency. The old saying that everything in the body is connected is not an understatement, but it is a bit of an oversimplification. That everything in the body has the potential to affect everything else in the body might be more appropriate.

The awareness of our body’s position in space is called proprioception. This is a broad concept that simply relates to the incoming signals the brain receives from the body so it knows how to move the body—how far, how fast, how powerfully—across multiple joints, muscles, and tendons. The brain receives this information via nerve receptors in our muscles, tendons, joints, and arguably even skin and fascia. It is what allows you to close your eyes and touch your nose without poking out your eye. Also without looking, you know that as you read this your left elbow is not fully straight and could tell us the angle of the joint with pretty good accuracy.

So if we put the two concepts of mobility and awareness together, the former will dictate what shapes the body is capable of making and the latter will determine how accurately those shapes are made. If you are trying to make a hypothetical circle but a joint is restricted, you’ve only made an oval. If your mobility is good, but you are lacking in awareness, then you’ll be making squares or pentagons because you can’t smooth out the motion required for a circle.

While I’ve just made the case that posture is a product of the whole body, it is commonly thought of as related to the spine. As the foundation of our movements and literally the center of the body, the spine is an ideal place to start.

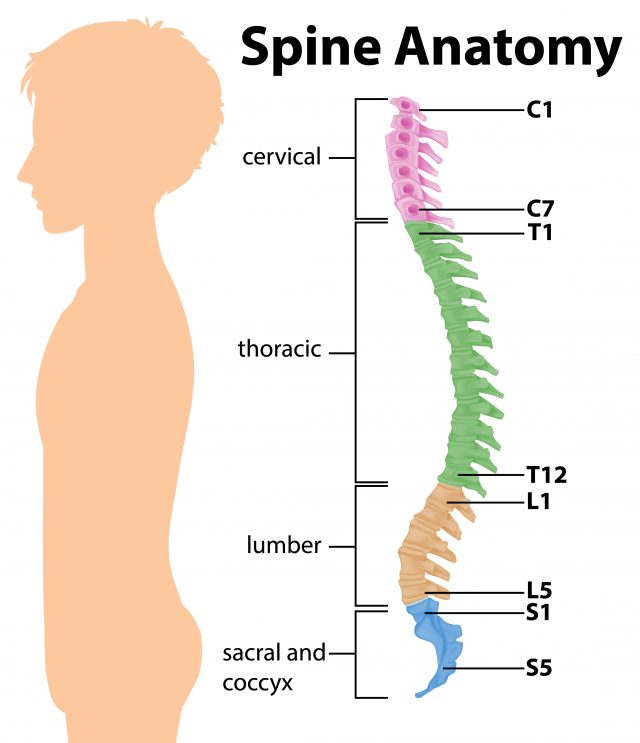

The human spine itself consists of 24 vertebrae with a skull on top and ending with the sacrum and coccyx. That stack of bones is held together by countless ligaments. Between each vertebra is a disc that acts as a spacer, a shock absorber, and as a pivot point for motion. The vertebrae articulate with each other through small sliding joints located bilaterally. The orientation of these joints, which changes with the region of the spine, will determine the available motion and optimal movement pattern. Running through the center of the spine is the very precious spinal cord. Simplistically, the spinal cord is a superhighway with on and off-ramps between every vertebra. It carries information both to and from the brain. Movement and dynamic stability are provided by numerous muscles, which we will get to in more detail shortly.

Basic anatomy having been covered, perhaps the more important implication for posture is the architecture of the spine. Contrary to the instructions to “sit up straight,” the spine, when looked at from the side, is not straight. (It’s not always straight from the front either, but the functional implications of scoliosis are beyond the scope of this article.) The spine, in fact, curves in a bit of an S from the head down in what is referred to as neutral spine. The cervical portion, comprising the 1st seven vertebrae, makes a concave curve. The next twelve vertebrae in the thoracic region have a convex curve. The last five in the lumbar are again concave.

The appropriate amount of curve in each region is also on a bandwidth; however, the curve in one region can have profound effects on another such that they cannot be looked at in isolation. Stop reading for a moment and “sit up straight.” Now tilt your head and look up at the ceiling. Make a note of what that felt like or what you saw on the ceiling. Next slump down like a texting teenager. Look up at the ceiling again. Any difference? You probably noticed that it was much harder to look up from the slumpy position. This is because the increased flexion or convex curve of the thoracic spine changes the starting point for the extension (looking up) motion that occurs in the cervical spine. Think about how this might affect your neck when sitting on a bike. You can do the same experiment with your arms. Sit up tall and raise your arms overhead. Then repeat in a slumped position. Much easier when done in a neutral spine.

A functional application here is how easily (and quickly) you can get your poles up to begin the next stride.

So what exactly does “good posture” or a neutral spine look like? Remember that a neutral spine occurs along a bandwidth of variability. Just as we all share the same basic anatomy, we all come in different shapes and sizes. However, the ears, shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles should generally line up while standing. Sitting is the same with a straight line connecting ears, shoulders, and hips. Again, there should be an inward curve at the low back and an outward curve through the mid to upper back. The neck will also tend to have an inward curve.

In clinical practice, the majority of postural deviations appearing outside of bandwidth tend to fall into two categories: excessive thoracic kyphosis (to much flexion or outward curve in the upper back) or too much lumbar lordosis (excessive extension or inward curve at the low back). It is also worth noting that in clinical practice, the research would tell us that there is no evidence of “poor” posture causing musculoskeletal pain and is merely correlated with pain—not everyone who slumps all day has neck pain; not everyone with “sway back” has back pain.

But posture that falls outside of the bandwidth creates an increased load on the body. The majority of nontraumatic musculoskeletal injuries arise as a result of an imbalance between load that is placed on the body and the body’s ability to tolerate load. So from a clinical perspective, improving posture is unlikely to be the Holy Grail, but it may be part of the solution, especially when a change in posture creates a change in pain levels.

Thoracic kyphosis tends to be an issue of mobility and/or awareness, at least in static postures. With dynamic movements, the complexity of the task may outweigh either the neuromuscular coordination or simply the requisite strength to maintain a neutral spine. Both of these scenarios will be discussed further in the next article.

Excessive lumbar lordosis that is observed in standing, but decreases in sitting, tends to be much more complex. A simple explanation may be that the knees are hyperextending while standing. This has a simple solution: Stop hyperextending your knees! But this is way easier said than done.

This is a pattern that has developed over years and is a tough habit to break. A much more complex pattern is one of relatively tight hip flexors along with relatively weak glutes and hamstrings. This effectively tilts the pelvis forward thereby increasing the curve in the lumbar spine. Again, this scenario might not be an issue with static posture but will be exacerbated by activities requiring hip extension such as running and skiing. This will also be covered further in the next section.

Sitting is the new smoking. If you spend long hours sitting in front of a computer, STOP! Not your job, but the prolonged sitting. Height adjustable desks have become much less expensive and allow you to move frequently between sitting and standing. My typical advice is to change positions every 20-30 minutes. Standing is likely better, but put in one position too long and we’ll still get lazy with posture. If you don’t have this option, getting up and moving every hour can help.

With both sitting and standing at the computer, keep your elbows at your sides and bent 90 degrees or a little less. When sitting, keep your pelvis vertical and all the way back in the chair. You should be on your sit bones. If you roll back onto your tailbone, it’s all over. The pelvis needs to remain vertical (or horizontal from front to back) in order to maintain a neutral spine. A lumbar support, or even a folded towel, placed in the small of the back will make it easier to maintain this position.

Maintenance of neutral spine with dynamic activities is no different, just harder. Again, posture falling outside of bandwidth equates to increased load which equates to inefficiency. Cycling is the easiest, at least conceptually, to transfer the ideals of sitting posture. It just requires tilting the pelvis forward on the saddle. “Bellybutton to the top tube.” Bike fit and hip mobility will both have a significant impact on how comfortably this can be accomplished.

Running, swimming, and classic skiing get more complex due to the inherent rotation involved; however, a neutral spine as observed from the side remains ideal. A full discussion of form and technique for these sports, excepting Nordic skiing, is well outside the scope of these articles. It should also be noted that the human spine is fully capable of motion in all planes. It should not be inferred that the spine should be forever fixed in neutral.

Stay tuned for the next part of this series which will dig deeper into spine mobility, stability, and proprioception.

Ned Dowling

Ned lives in Salt Lake City, UT where his motto has become, “Came for the powder skiing, stayed for the Nordic.” He is a Physical Therapist at the University of Utah and a member of the US Ski Team medical pool. He can be contacted at ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.