Spinning past the autumnal equinox into fall, the West looks back on a summer marred by wildfire smoke. Here in Colorado, the Aspens have dropped their golden leaves, snow encrusts the high peaks, and I’m struck by the beauty of my backyard, which spent the majority of June, July, and August muted by smoke that — thankfully — blew in from elsewhere.

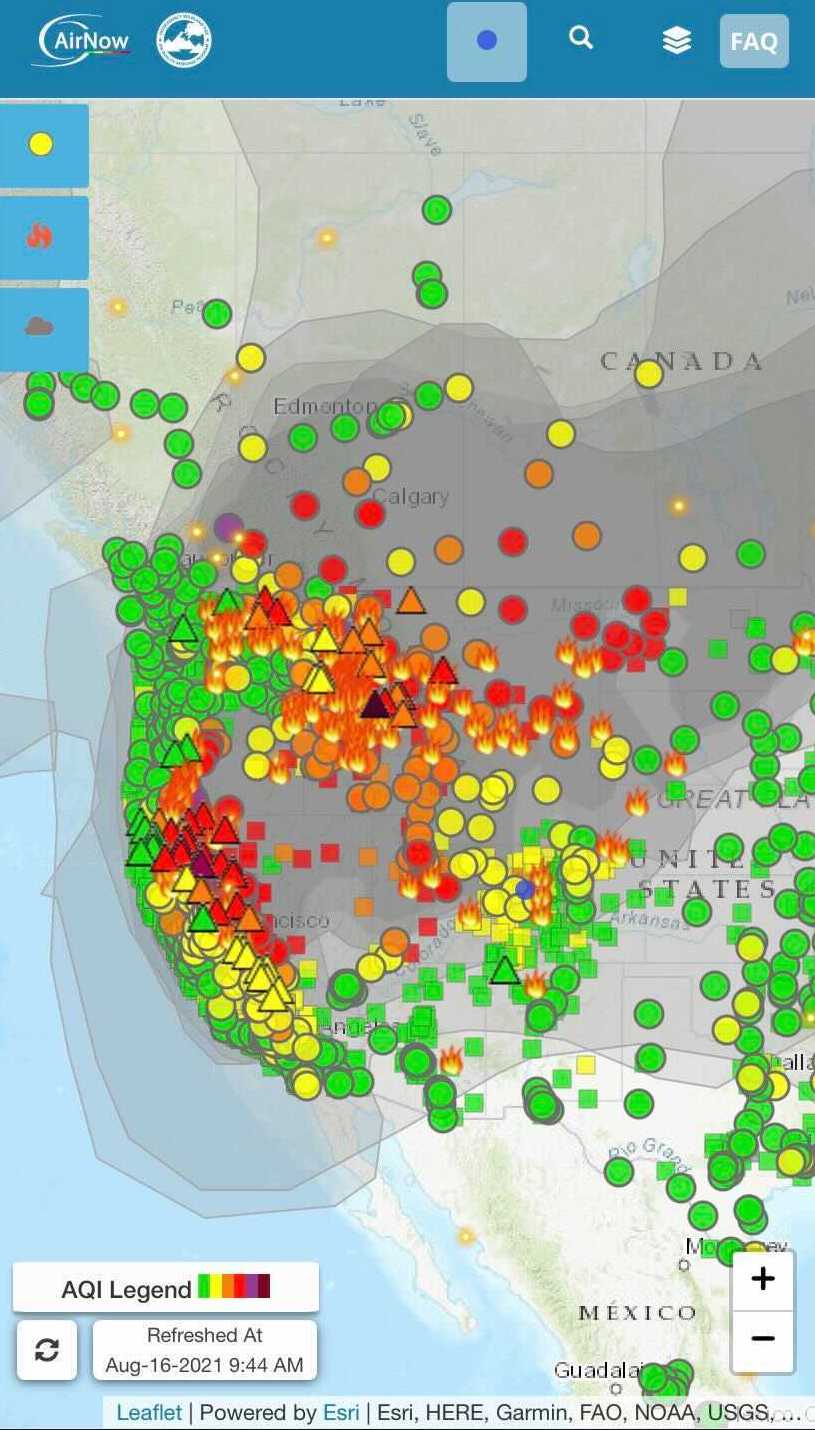

Over the last six weeks, checking AirNow before training has been phased out of my morning routine, and there is a palpable sigh of relief within my community as rain and high country snow frequent the forecast. The fire danger is not gone, but the threat feels less omnipresent.

While regions like California, the Pacific Northwest, and Montana perhaps faced the longest durations of acrid high-AQI haze, cross country ski communities nationwide experienced its effect. As particulates from these fires were swept across the country, even air quality in the Northeast dipped into unhealthy zones for periods of time.

This phenomenon is not new, and as the planet continues to heat up, the West will be faced with longer and more devastating “fire seasons”. While sport might seem insignificant relative to the scale of issues at play, learning more about the modifications teams and athletes might consider can support the cross country ski communities overall health and wellbeing.

FasterSkier connected with coaches from areas heavily affected by fires and smoke to hear more about how they managed the impact in terms of protocol and adjustments to training with their athletes. Coaches also spoke to the increased frequency that these decisions will need to be made as climate change progresses.

First up is Andy Newell, head coach of the Bridger Ski Foundation Pro Team in Bozeman Montana.

“Air quality and training is definitely a concern particularly because there’s not a ton of research about how smokey air affects high level athletes. We know a little bit about the short term implications but not much about long term exposure for athletes. The reality is this is something a lot of western clubs have been dealing with for a while but now we are seeing a lot of smoke in the midwest and even the east too.

“On a typical year in Bozeman we usually don’t see smokey air until August and even then it’s not as bad as many other parts of the Northwest. This year we saw smoke earlier than ever, around the middle of July and early August, but much cleaner air than normal in the last few weeks. It really depends on wind, the jet stream, and where the big fires are burning. So far this year we have had to adjust about 3 workouts to bring athletes indoors when the air was bad. I’d say that’s about average for us, 3-6 workouts per year disrupted because of smoke.”

Newell continued by discussing the tools his program has used for decision making with regard to air quality and athlete safety.

“One of the things I have learned is that air quality can change very quickly and iPhone readings are not always accurate. We use the VisualAir app for forecasts and to find training areas that might provide better air for training. In this app you can see which sensors are gathering data from satellites and which ones from the ground. We’ve found obviously that the ground readings are a lot more accurate. Another thing we notice here in Bozeman is that the air quality can be very different even within the same region depending on high or low pressure, inversions, etc. So if you notice poor air at low elevations we might modify training and go up into the mountains and this can make a big difference.

“We do use general guidelines at BSF to keep the athletes safe. If the AQI is above 100 we’ll start to monitor things and potentially modify training. If we are between 100-150 we will cut out L4 training or consider bringing athletes inside on treadmills for aerobic training. Also in this 100-150 range we’ll consider using KN95’s while out for easy distance training. Luckily we’ve only had to do this once this year so we’re hoping we make it through fire season without much more disruption.”

A long-time advocate for climate policy and spokesperson for Protect Our Winters (POW), Newell closed with a statement on the impact of an ever-warming planet.

“As an athlete that has worked on a lot of climate issues this is definitely a scary reality, it goes to show you we are all affected by climate change.”

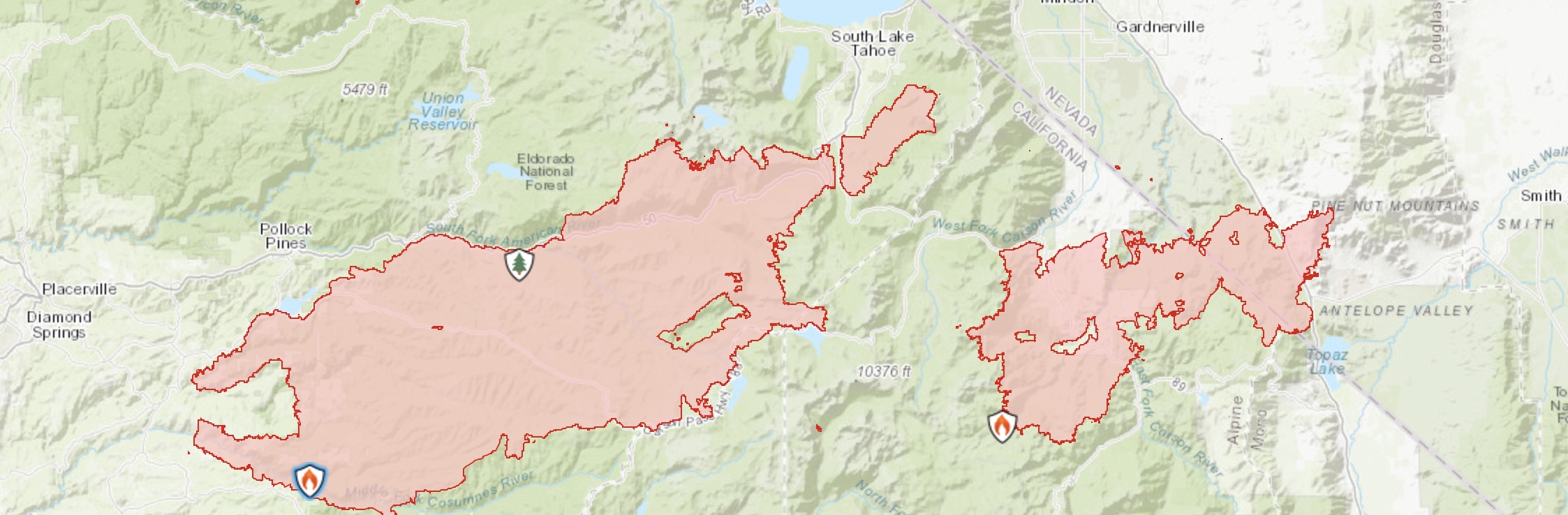

Heading Southwest, FasterSkier also corresponded with Will Sweetser, Director of Nordic Programs for Sugar Bowl Academy (SBA), northwest of Lake Tahoe. The Tahoe region was struck hard this summer, as the devastating Caldor fire ripped through nearly 220,000 acres and destroyed over 1000 structures.

Now 98% contained, the Caldor fire remains active, over two months since it began on August 14th. It has burned over 220,000 acres, an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Although the fire is still active, most evacuations and closures have been lifted.

Sweetser first outlined the nuts and bolts of air quality considerations. For those unfamiliar, AQI considers the concentration of fine particulate matter in the air. Particulate matter, like wildfire smoke, that is 2.5 microns or less (PM 2.5) is most concerning, as it can penetrate deeply into the lungs.

“Train as usual if school is in and AQI is between 0-60; offer optional/slightly modified training — consider shortened length first, and reduce continuous intensity — when AQI is between 60-120. Optional training is reduced, and outdoor training is only recommended for healthy, unaffected individuals when AQI is 120-150. Sessions are capped at 1 hour, and intensity capped at L2.”

While indoor recreation amidst the COVID-19 pandemic poses its own set of complications, Sweetser explained that indoor training is preferred when the AQI is above 150. To support the health of its athletes, SBA has integrated air purifiers in every indoor space on its campus, including classrooms, common areas, dining halls, and the gym. These filters help maintain an indoor AQI of 25 or below.

“In heaviest smoke events, we encourage families with the capacity to travel to cleaner air for the week to do so within the confines of school requirements. If we are in a remote schooling period, which was precipitated by Tahoe area evacuations last week, many families simply move to second homes in the Bay area or elsewhere in CA. We write individual suggestions for each athlete to meet the training options in that area. Our general week plan (MON–OFF, TUE-WED-THU–heavier training 1-2x daily, FRI–recovery, WEEKEND–high training load/family outings) readily allows families to take weekends away for cleaner air.”

When Sweetser was first contacted in late August, he responded that he was with the team on the coast enjoying a training block in fresh air. In his email afterward, he included the purpose of this camp.

“Last week, we utilized our first planned smoke escape team training weekend. It was in the school travel calendar. Teachers prepared some work in advance. The entire team went to the north coast of California for FRI-SUN. We had 5 excellent training sessions, including 1km L4 repeats, pure speed double pole session, 2 technique sessions and a 15-20-kilometer run. AQI in the Mendocino area varied from 8-43 during that time and was a great reset for us. Extremely valuable to get to clean air, sea level and group training in a pretty stressful time. We are lucky to be able to do so with just 4-5 hours driving.”

When the team is not able to travel and air quality is poor, Sweetser explained how they approach indoor training to achieve similar stimuli to those they’d seek in “normal” conditions outdoors.

“When we are on Donner Summit with poor AQI, we utilize gym time and treadmill/SkiErg sessions to offer modified indoor sessions that still reflect each athlete’s goals — often these sessions are shortened and feature slightly more L2, or intermittent work, than we might normally do outside — although looking at HR data, the planned intermittent nature of these sessions is not totally different than sending the crew for a trail run through rolling terrain.”

Sweetser also reflected on the learning curve for appreciating how quickly AQI can change based on wind and weather patterns. He recalled leading an OD training run with a couple of his athletes and assistant coach David Sinclair that began at a borderline AQI of 120. As they progressed toward the objective, Hawks Peak, the air quality plummeted.

“We could see smoke pouring in from the north as we headed across the ridge… We called parents for pick up and dropped down as quickly as we could.”

By the time the athletes reached their pickup point, the AQI was over 400, which is considered emergency conditions.

“What I keep in mind is that we are really training for a healthy body and mind for the long term. That no one day, week, month, or even whole season is so critical that we potentially sacrifice our long term health for a short term result. In this sport, any short term results we achieve are very unlikely to bring us any benefit other than good health. Cold weather injury is a serious consideration in skiing. Regular exposure to air pollution, wildfire smoke included, is just as — and I would argue more — serious.

“You don’t know what sort of interruptions you will face in a year. Modifications to training happen for conditions all the time. It is built into our sport. Weather, lack of snow, too cold, not cold enough, smoke. Add sickness, a hard semester, family needs, and so on. For those reasons it is always a good idea to work ahead. When it is good you go and that way when conditions are bad you don’t have too. You don’t need to feel the pressure to make up for something you didn’t do.”

The MBSEF programs had been following similar guidelines to SBA, however, Watts responded that after the World Health Organization’s release of new air quality guidelines at the end of September, the program further tightened its tolerance of poor air quality. With mounting evidence of the increase in all cause mortality risk due to prolonged exposure to pollutants, the WHO drastically reduced the acceptable levels of PM2.5 and other pollutants individuals should be subjected to in both short and long term settings. The 300 page document also calls for a global response to air quality improvement.

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646