White-knuckled, we caravanned down I-94 from St. Cloud to Minneapolis in the midst of a bomb cyclone of wind, snow, and ice. Braving the conditions, we crawled toward our destination: the 2021, hybrid City of Lakes Loppet at Theodore Wirth Park. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic—and a hearty desire to stay healthy for the remainder of the ski season—we decided to drive separately. Now, we were inching our way to a late start for our Thursday morning staggered start times of 9:00 and 9:02. There was no way we’d make it on time.

As race directors presented various solutions for completing their races during the winter of 2020-2021, many Nordic skiers were scrambling to salvage a season that had been fractured by a global pandemic. Previously, we had gathered en masse at venues in Minneapolis, Hayward, Calumet and numerous other host towns for days of socializing, racing, and celebrating. Now we found ourselves with virtual starts at different times and venues scattered across North America. Armed with smart watches, cell phones, or (in some cases) witnesses willing to testify to distance and time, cross-country skiers raced their way to another successful event completion. As we all uploaded our times and compared our performances, we were left wondering about the legitimacy of these “virtual” races: were we really racing? Against whom? These questions got us thinking whether these virtual race formats—including skiing different venues, at different times, or even substituting an activity other than skiing—are viable long-term solutions to hosting Nordic ski events in the face of climate change, where winters are getting warmer and the ski season is getting shorter with less predictable snowfall.

To address these issues, we developed a survey to gather the insights of Nordic skiers across North America. With the help of the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation, the Loppet Foundation, and Stearns and Wright County Parks, we received feedback from over 1,300 participants. In our first article, we addressed the question of how we self-identify as cross-country skiers and how this relates to culture, diversity, and opportunity in our sport. In part two, we focus on skiers’ perceptions of virtual ski events, our likes and dislikes, and whether these are legitimate forms of racing. To address these questions, we evaluated a subset of our survey participants: the 829 cross-country skiers who completed at least one virtual ski event during the 2020-2021 ski season. Thus, while our survey results aren’t necessarily a reflection of the entire Nordic ski community, they do represent the voices of skiers who experienced firsthand the pros and cons of virtual racing.

Racing? Virtual?

As we try to better understand how our cross-country ski community responded to the COVID-19 race schedule—and what it means as we move into a world of less predictable winters—two terms become particularly important: “virtual” and “racing.” Although we may all have a general idea about what these terms mean, neither is particularly straightforward as we look at the myriad opinions regarding the “virtual race” schedule of the 2020-2021 race season. For our own purposes, as skiers who practice anthropology, the two terms vary in how they are defined. Although countless articles have been published on the philosophy of racing and what constitutes a race, the term “racing” in our study is one that we left to our survey participants to define. This means that we are not going to provide a definition of “race” or “racing,” at least not yet. Instead, we teased the meaning of cross-country ski racing from the responses that our Nordic ski community provided in the survey. Thus, “racing” is defined internally, by the skiers. We own it.

On the other hand, the term “virtual” is one that was defined for all of us, at least as it applied to the COVID race season of 2020-2021. And the definition of “virtual” might have strayed a bit from what we normally think of as “virtual.” For the most part, the virtual options presented to us for completing our annual ski marathons didn’t involve pulling out the VR headsets or hopping onto the treadmill or trainer for a Zwift or Rouvy session—though in some cases, it might have. Instead, virtual options included such things as actually skiing on snow, but in a different location than the original race, or skiing at the official race venue but on a different day than the traditional start. For some races, such as the American Birkebeiner, other activities such as running, cycling, swimming, rowing, or roller skiing could be substituted for skiing on snow (Figure 1). Regardless of activity choice, substrate, and location, distance and time were measured using a GPS watch or app, or the testimony of a witness who could verify time and distance. We got to choose how we completed our events given a range of “virtual” options that were made available to us. Although COVID is not currently the threat it was two years ago, at least some event organizers are still offering virtual options this winter. The virtual option could turn out to stick around longer than many of us anticipated.

Do we dislike virtual events?

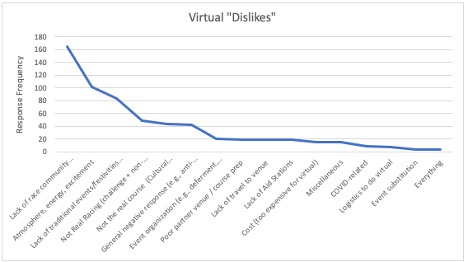

As we perused our survey results, we were struck by the wide range of responses, both positive and negative, that skiers had with the various alternative cross-country ski formats subsumed under the term “virtual.” We noticed that, given the opportunity to discuss both their likes and dislikes of virtual racing, positive responses (n=864) outnumbered negative responses (n=613) by over 30%. A look at these results allows us to get a handle on how we, as a community, define racing as well as our attitudes about whether virtual cross-country ski events can be considered legitimate races. We’ll begin our discussion with the dislikes that virtual skiers expressed about the events they participated in.

Figure 2 summarizes the 613 individual, negative responses that virtual ski participants provided. Overwhelmingly (> 55%) the dislikes about virtual cross-country ski events focused on the lack of social interactions, energy, and festivals that surround typical Nordic ski races. The single, most common dislike (n=165) that skiers expressed was that they missed the community and camaraderie that surrounds these events. This was followed by the lack of atmosphere, energy, and excitement (n=101), and lack of traditional events and festivities, including things like gear expos, after-parties, and “Main Street” finishes. Following these first three dislikes, we see a drop in responses.

Coming in at number 4 in the list of dislikes, with 9% (n=49), was the critique that virtual events, in one way or another, are not real racing. Although only 17 of the 629 dislikes explicitly stated that virtual events used during the COVID-19 pandemic did not constitute real racing, we identified several additional responses that are closely related to this category. These additional “not real racing” responses do two things: 1) they provide valid critiques of virtual events; 2) they identify important elements of a ski race that allow us to tease out the definition. Fifteen respondents argued that virtual events lack competition. Additional critiques include non-comparable times (n=10), no official, mass start time (n=4), and that virtual event participants ski on different courses in different places (n=3). This mix of responses highlights some key elements that define a cross-country ski race: a competition between skiers where times are legitimately comparable because of a scheduled start time on a designated course using official timing.

So, when we (M&M; Figure 3) were slipping down I-94 to ski the hybrid City of Lakes Loppet, would we be racing? Technically, we missed our start times, so that criterion might be compromised. However, we were still allowed to race, and we certainly skied within the open window for the event. When we got to the start on Wirth Lake, it was empty except for a volunteer starter who explained the course, and particularly the finish, where we were instructed to do two laps around the stadium. We were competing with the clock, but also with other skiers that we might have seen on the course. We also compared our finishing times with those who completed the event at different times and on different days. Whether or not we skied the same course is a sticking point. By the time we got to the final 10k around the stadium, the conditions had degraded to the point where drifting snow and downed course markers had made identifying the intended course impossible. Tornow’s two laps differed slightly from each other, as evidently he missed a turn at some point. Muñiz did the same lap twice to finish his race. This resulted in different distances: 30.5k for Tornow and nearly 34k for Muñiz. While the official race distance was recorded as a 30k, other racers recorded different distances too. Maps posted to Strava show that Olympians Caitlin and Brian Gregg each skied 31.2k to complete their hybrid Loppets. While some differences in distance are almost certainly the result of different recording devices (e.g., watches, phones) and related apps, it’s also evident that Tornow, Muñiz, and the Greggs all skied slightly different courses for the same race. Without analyzing the maps of all participants in the 2021 hybrid City of Lakes Loppet, we really don’t know how our times compared with the other racers. Similar concerns might arise from skiing the same course at different times. Our late start on Thursday morning resulted in more accumulated snowfall on the course and more drifting. We’re not making excuses, but those who skied the race earlier in the week or the following day would have had very different (better) conditions. Apply this complexity to events that allowed skiers to use entirely different courses (e.g., Virtual Birkebeiner and Virtual Vasaloppet) and we can quickly see that the race criteria of legitimately comparable times and distances are easily violated for virtual events.

Rounding out the top five dislikes, skiers did not like the fact that they were not skiing on the real course. This is a sentiment that, like the top three responses, relate to the social aspects of the event by focusing on the traditional place and cultural landscape where cross-country ski events occur. These top five responses (72%; n=443) all focus on the social meaning of the event, whether it be interpersonal relationships, competition between ski racers, or interaction with a traditional, cultural landscape.

Rather than focusing on the cultural meanings associated with cross-country ski events, the remaining 28% of dislikes shift the focus of critique to the mechanics of virtual racing. The sixth most common dislike was a general, “virtual stinks” kind of response. While not explaining why they disliked virtual events, these 42 responses express a general dissatisfaction with the substitution of virtual events for traditional, in-person, mass-start races.

There is a sharp drop in the number of responses following the “virtual stinks” critique. Twenty virtual skiers were dissatisfied with the organization of their virtual events. These dislikes ranged from a lack of communication and dissatisfaction with virtual interaction to the inability to defer their registrations to future, in-person events. There was a three-way tie for the eighth most common dislike between: dissatisfaction with partner venues and course prep; the lack of aid stations; and a desire to travel to the host town for the event. Rounding out the dislikes were the high cost of virtual events (n=15), a general dissatisfaction with the situation surrounding COVID-19 (n=9), figuring out logistics (n=8), and event substitution (n=4). There were also fifteen “miscellaneous” responses that included things like not winning a raffle, missing foreign culture, and lack of motivation.

What was there to like, then?

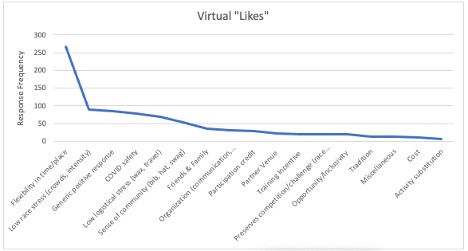

With all of the negative feedback, we’re left wondering if there was anything we actually liked about these virtual events. It turns out, that there was a lot to like, and skiers had about 30% more good things to say about their virtual races than bad things. Figure 4 shows that about a third of survey participants (n=266) said that they liked the flexibility that virtual ski options provided regarding when and where the event could be completed. For virtual events offered during the pandemic, skiers could choose their own venue and could complete their races at any time. This was clearly a bonus to many skiers. The next most common like (n=89) was the lowered race stress that comes from virtual events. Although many skiers disliked the fact that virtual racing wasn’t real racing, a greater number of skiers indicated that they liked the lower stress, less-crowded trails, and lower intensity of virtual race formats. Following a general “virtual is great” response and an appreciation for COVID safety (which came in third and fourth, respectively), the lower logistical stress afforded by not having to travel, figure out wax, and get to the starting line on time rounded out the top five. Thus, three of the top five likes of virtual racing were related to the fact that the virtual events were fundamentally different than typical races and were generally less stressful.

Although the top three dislikes of virtual events revolved around missing the sense of community that big cross-country ski events provide, not all virtual racers saw it this way. The sixth most common thing that skiers liked about virtual events was the sense of community that they created. The sense of community resulted from seeing others skiing their virtual events in their race bibs or displaying the swag that comes with participation in hallmark ski events. For many racers, wearing Birkie swag publicly associates them with finishing one of the toughest ski marathons in North America. Whether or not they finished the race on the course in Wisconsin or on a local trail in some other state is a secondary talking point. Others also appreciated the opportunity to ski with friends and family who had different abilities (7th ranked). Thus, virtual options provided a real sense of community, albeit different from that found with traditional mass gatherings.

There were a number of skiers who were happy that, during the middle of the COVID pandemic, races were held at all, and many of these folks (n=31) gave ‘shout-outs’ to the organizers who pulled these virtual events together, maintained communications, and provided platforms for reporting results. In addition to praising the race organizers, 23 skiers also gave kudos to partner venues, who provided certified, groomed courses to use specifically in completing the virtual Birkie. Squeezed between organizer and partner venue shout-outs, the ninth most common like about virtual racing was getting credit for participating. This sentiment ties into the fourteenth ranked like (n=14): preserving tradition. For many skiers, participating in these events is steeped in tradition, and the chance to participate in a COVID-safe, socially distanced format provided skiers the opportunity to keep the tradition alive (Figure 5).

Although very few positive responses explicitly called their virtual events “races,” the racing sentiment is expressed in some of them. Twenty-one skiers liked that the virtual options available to them provided impetus to continue their race training. An equal number of skiers liked that virtual events preserved the challenge and competition of a race experience. Thus, while about 9% of virtual participants thought of virtual racing as “not real racing,” 5% liked the racing aspects of virtual events.

Just as virtual events provided skiers the opportunity to ski with friends and family with different abilities, they also provided opportunities for skiers to take part in events that they might not otherwise have been able to participate in. Our data indicate that about 10% of our total number of respondents (127/1300) had never completed a sanctioned, Nordic ski event prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of these 127 skiers, 42 (33%) indicated that they took part in a race during the 2020-21 season and 34 of them chose a virtual option. Whether the virtual option provided impetus for these first-time cross-country ski racers to participate in these events is unclear. What is clear is that 20 skiers indicated that they liked the opportunity to participate that the virtual options provided. Thus, for these 20 skiers at least, virtual races provided the opportunity to participate in ways that otherwise might not exist.

Aside from cost and a number of miscellaneous responses such as adjusted, shorter distances, or positive memories associated with a chosen alternative venue, the likes are rounded out by those who appreciated the opportunity to substitute an activity other than skiing to complete their event. This was a big bonus to skiers who found themselves on a snowless landscape during the COVID-19 pandemic.

So where does this leave us?

If we look at the sheer numbers of likes versus dislikes, it’s clear that virtual skiers had more good things to say about virtual events than bad. Does this mean that virtual skiers liked their respective events? Maybe. There were certainly things to like about the opportunities provided to “race” under the social distancing guidelines of COVID-19. Simply the fact that we could ski at all was enough to make many skiers happy. Add to that the flexibility, inclusivity, low stress, and opportunities to socialize and compete, and the virtual response to COVID seems like a success. Of course, the lack of community, excitement, and celebration seemed to weigh heavily on virtual ski participants. While many skiers liked the lack of stressors and logistics that come with virtual racing, many of those same skiers disliked the fact that these virtual events weren’t “real races.” So, what is it about a “real race” that is so appealing and motivates us? It’s something more than just legitimately comparable times because of standard starts on a designated course using official timing. Real races require honest head-to-head competition between us as we strive to do our best, that pushes us to be even better than we could ever be on our own. If virtual races cannot provide this, then they fall short for many people.

Holding our ski events virtually during a time when hosting mass gatherings was neither practical nor safe was probably the best solution. As Ben Popp, Executive Director of the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation, said “while it isn’t as good as an in-person event… it was still something that you planned around, talked about and went and did. It kept you engaged in a larger community and working towards a goal.” But, as winters become more irregular, with warmer temperatures and less predictable snowfall, is this format something that skiers would accept on a more regular basis? What would a transition to virtual ski events do to our sense of community? To our desire to compete? These are questions that we’ll address next, as we explore the impact of virtual events on the Nordic ski community and culture and consider the ways that event organizers can maintain or even grow participation in our sport in light of climate change.

Mark P. Muñiz, PhD, is a Minnesota transplant who grew up in Florida, but enjoys a cold snowy winter over a hot humid summer any time. His cross-country ski adventures have included loppet races and volunteer coaching for the Minnesota Youth Ski League. In the warm season he loves cycling and is still a little wary of jumping on rollerskis. He currently teaches as a Professor in the Dept. of Anthropology at St. Cloud State University, MN.

Matt A. Tornow, PhD, is a Professor of Anthropology at St. Cloud State University in Minnesota. His research interests focus on primate adaptation and behavior, including that of humans. As a native of central Illinois, he spent much of his youth and early adulthood driving north to seek out the snow. Now he spends his winters skiing the local trails and doing a little racing. When there’s no snow on the ground, you can find Matt running through the woods somewhere.