If you’ve ever set a lofty athletic goal, one that required full commitment, going all in and pulling out all of the stops to optimize your training, you may have searched for strategies to similarly optimize your recovery between sessions, getting you back on the ski trails feeling strong as quickly as possible. In this process, you may have found yourself perusing a seemingly endless array of devices, foods, and drinks, each promising to improve your ability to bounce back from workouts sooner, thereby allowing you to train harder and more often, which is seemingly a win-win scenario.

Before buying into these claims – literally and figuratively – a recently published book suggests it may be wise to first pause and consider that the benefit that these products promise might be too good to be true.

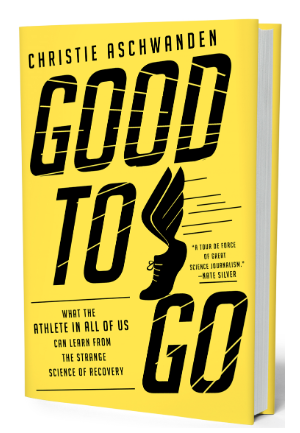

In “Good to Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn From the Strange Science of Recovery”, Christie Aschwanden presents the findings of an in-depth look at the research (or lack thereof) behind the leading players in the industry of athletic recovery. Her analysis includes everything from electrolyte drinks to cryotherapy chambers to massage. She leaves the reader with a healthy dose of skepticism and perhaps a bit of reprieve from the hype surrounding the recovery obsession. Peppered with relatable anecdotes from her own experience as both an elite and recreational athlete, “Good to Go” is a worthy read for any competitor from master blaster to elite.

Beyond delving into research and trying these products herself, Aschwanden is no stranger to the world of high-performance training and competition. If you’ve been following the sport for a while, you might recognize her name; the 47-year-old is a former member of the Team Rossignol nordic ski racing group, despite the fact that she did not begin skiing until college when an injury prevented her from competing as a Division I runner at the University of Colorado Boulder.

While injured, she joined the cross country ski development team at CU and also took up cycling, quickly becoming an elite level competitor in both. In her ski career, Aschwanden toured North America racing in the marathon circuit and in Continental Cup races. In 2002, she and her husband moved to Switzerland for two years. While overseas, she joined the Swiss Rossignol team and competed in several Europa Cup races. She continues to ski, run, and mountain bike recreationally, occasionally hopping into races in the area around her home in Cedaredge on the Western Slope of Colorado.

In addition to being a lifelong endurance athlete, Aschwanden is an accomplished science writer, frequently contributing to a variety of publications including the New York Times, Runner’s World, NPR.org, Discover, and the Washington Post. She is also the co-host of the podcast Emerging Form, which is about the creative process, and a frequent speaker and instructor at science writing workshops and conferences nationwide.

“Good to Go” opens with the author’s own foray into the field of scientific research on athletic recovery to understand the age-old question, “Is beer good for recovery?” to which she hoped to find the answer, “yes.” She walks readers through the development and execution of the study, which involved a group of ten athletes completing a 45-minute treadmill run at 75% of their VO2 Max effort, then drinking either a Fat Tire Amber Ale, made in Colorado by New Belgium Brewing Co., or a non-alcoholic O’Douls. These beers were chosen for their likeness in color. The following morning, the runners would complete a “run to exhaustion” at 80% of their determined VO2 Max.

After designing, participating in, and analyzing the results of the study, Aschwanden found herself with a greater understanding of the flaws of scientific research in the arena of recovery, primarily, the impact of the easy intrusion of personal bias, the lack of quality placebos (one does not need to be a sommelier of beer to tell the difference between Fat Tire and O’Douls), and the opportunity of false positives created by repetition of small studies.

Aschwanden writes, “For one thing, I discovered that it’s not enough to ask ‘Does this thing work?’ First, you have to start with more fundamental questions: How would we know if it’s working? What are the benefits that this gizmo or ritual is supposed to deliver, and how would we measure them? If the proof is coming from something measured in a lab, do those numbers translate into meaningful differences in real life? As I found out during the run to exhaustion test, just because you can measure something doesn’t mean it’s answering your question.”

As she leads her readers through an illuminating tour of the recovery industry, Aschwanden exposes the critical influences that affect whether the research performed on a product truly validates the claims being made, or if they are “just-so stories,” a reference to Rudyard Kipling’s classic collection of tales for children which provide fanciful explanations for how leopards got their spots and camels got their humps . She explains how celebrity endorsement and social media can greatly influence a consumer’s choices, and that some studies have been funded by the company that produces the product. These conflicts may lead researchers to design their experiments in a way that is likely to produce favorable results.

While she remained open-minded and found the exploration of products and research surprising, Aschwanden explained she was predisposed to skepticism given her history and credentials.

“Having a background in science and athletics, I knew that if someone is making a claim that seems too good to be true, it probably is,” she said in a call. “So many of these products make really outlandish claims. At the same time, I realize how susceptible we athletes are to a lot of these things. They really exploit this doubt that ‘Well, maybe it does work a little bit.’ And when you’re competing at that level, you want every single advantage you can get and you don’t want your competitors to have some advantage that you don’t have.”

The power of placebo is a common theme throughout “Good to Go”, capitalizing on the doubt Aschwanden referenced. In terms of product research, the control group of athletes knows whether or not they are taking an ice bath, getting a massage, or spending half an hour in inflatable compression boots, and there is not a great way to make all participants believe they are receiving the same treatment. Thus, if the participants believe that a product will work, the placebo effect just might allow them to show improvement from its use.

In some cases, the product might be useful purely because it forces an athlete to take a break, lie still, and decompress while the body uses its natural ability to recover.

“Many popular recovery modalities strike me as a sort of pacifier,” she writes. “They won’t actually resolve anything, but they give you something to do while you wait for nature to take its course.”

She offers a strategy of placing the recovery tools, consumable products, and services into one of four bins. Which bin a recovery strategy is placed into is customized by the individual.

“First is the ‘feels so good’ bin,” Aschwanden explained in the eleventh chapter. “These are the things that feel good while you’re doing them, and perhaps afterward too, which even if it does nothing else, provides a valuable benefit in itself. Next is the ‘hurts so good’ bin, with things like icing that are painful, and thus give the sense that they must be powerful (and therefore effective). Third is the ‘it’s working, I can sense it’ bin of active placebos, with things like cupping, which produce noticeable sensations and effects that aren’t necessarily painful nor alluringly pleasant. Finally, there’s the ‘blinded by science’ bin of things like infrared saunas, whose appeal comes from jargony scientific explanations that give them an aura of space-age power.”

One discovery which has made waves in the realm of physical therapy and athletic performance is that icing to reduce muscle soreness and promote recovery is a fallacy. In her cycling days, she recalled taking ice baths regularly, particularly during stage races.

“There are still some reasons that it might be good to ice,” she explained. “If you’re cycling on a really hot day, and the summers have just gotten so much hotter, jumping in a cold lake or something can be a good way to get your body temperature down and that’s good for recovery. But the idea of icing in order to reduce muscle soreness or improve recovery, it turns out, more than just not being backed up by science, in some cases can be harmful and can reduce your adaptations to training, and that was really surprising to me. It’s just such an entrenched practice that it just didn’t seem that it could be as ineffective as it is.”

Ultimately, Aschwanden explains that the best recovery tool out there is one’s own body and mind. She advocates that athletes of all abilities tune into the messages their bodies are sending and trust the process in their own training.

“The most important skill that any athlete can develop is the ability to read your own body, to learn to understand and recognize the cues that it gives you, and those cues are really individual,” she explained frankly. “There isn’t one thing that is universal among athletes, but every athlete will have some clue that they can learn to recognize. Part of this is spending less time looking to see what your competition is doing and really focusing on yourself and how you’re adapting to your training and how you’re feeling on a day to day basis. I think part of this is also a confidence in your own fitness and your own training program. You have to be confident and be confident that when your body is telling yourself it’s tired, that [rest] is actually what it needs.”

While some may not find the recommendation as sexy as an infrared sauna, she explains that the best avenue to optimize performance is to get plenty of quality sleep and to eat a nutritious and well-balanced diet. From her experience, this can be a challenge for athletes that are on the road regularly during the competition season. In her book, she shares strategies that the pros use when bouncing around between venues and time zones. She also explained that the impact or travel, or other life events, should be taken into consideration in the same way that a hard workout might be.

“I think that people don’t always appreciate the extent to which, to your body, stress is stress,” she said. “Life stress is just as important as your training stress. I think that I was chronically overtrained when I was a skier, and part of it was that I didn’t appreciate the toll that travel was taking on my body. I didn’t appreciate that when I wasn’t getting enough sleep, that was impairing my ability to recover.”

In the world of Strava and social media, it can be hard for the recreational athlete not to succumb to “FOMO” (fear of missing out). It can be difficult to hold back from chasing PRs or adding more volume or plowing through the “niggles” until you are sidelined by a full blown injury or crippling fatigue. Aschwanden explained that the answer to improved performance is rarely to train more or harder.

“Too often, I think that I was trying to do as much training as I could tolerate, and I think that’s backward. I think it’s a much better strategy to do the minimum training that will get you the adaptations and the fitness that you’re seeking, because training is stressful on your body, so you want the training that you’re doing to really be benefiting you and having the effect that you have. I think I ended up doing too many junk kilometers and too much training when I would have been better off resting more.”

Her final piece of advice to athletes is to identify a strategy that helps them unplug and unwind, be it as simple as curling up on the couch with a book or as strategic as scheduling a massage.

“Find a way to incorporate some sort of daily ritual for relaxing, because really, at its most basic level, recovery really is just rest and relaxation. So many of these recovery tools are really just ways to ritualize taking a break or unplugging or resting. If you’re doing something that is helping you to relax, then that’s fine, but know that it doesn’t need to be something expensive or super time consuming or effortful, that it should actually be something that feels really easy and makes you feel good.”

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646