As endurance athletes, and especially as cross country skiers, we like to suffer. We enjoy a sport that takes place in the coldest months of the year and requires both strength and endurance to climb big hills and descend on skinny skis with no edges. We like to breathe hard. Most of us are in it for the suffering and the healthy dose of chemicals that our bodies release when the heart rate goes up and the muscles begin to burn. The runner’s high, an endorphin rush, pick your preferred phrasing.

Hopefully, we’re smart enough by now to know that we can’t go hard all of the time, at least not without consequences. The really smart among us are able to listen to their bodies and know intuitively when they can step on the gas and when they need to back off. But the rest of us could probably benefit from some type of external governor besides the voices in our heads egging us on, or constantly available Strava competition taunting from inside our pocket.

If life was just eat, sleep, and train, the calculus of easy/hard or short/long might be pretty easy. But work, school, kids, relationships, global pandemics, and social media bring no shortage of life stressors. And, physiologically, these life stressors can load the body just the same as an interval session. Stress is stress, and stress takes a toll on the body.

So, your training plan might call for a hard session, but what if work was crazy, the kid kept you up all night, and you made the mistake of reading the news headlines this morning? Is your body in the right place to make the workout productive? (Or at least not detrimental?) How do you know?

I think the honest answer is that we don’t always have an answer, but there are some metrics that can help us shape a well-informed guess.

Since Polar introduced the first functionally useful heart rate monitor in 1984 and Garmin gave us the GPS watch in 2006, wearable training technology has evolved considerably. Current wearables can track — and thus quantify — everything from steps to sleep to intensity. I don’t dare dive into that vast sea except to highlight and discuss what metrics might be the best at answering our question, “How hard should I push myself today?”

But before we even get there, it’s worth having a quick refresher on some principles of training, exercise, and activity. Depending on your goals, Nordic skiing can be an activity that simply gets you out in nature, a tool to maintain fitness for other sports like cycling or running in the winter, or it can be a year-round focus with time on snow dichotomized into either training or racing. In any of these scenarios, the cumulative load on the body is a very important variable to manage.

Too much load and we stop having fun, plateau or lose fitness, and begin to risk injury. Too little load and we don’t progress, but I doubt that’s an issue with the majority of us. We must also remember that the basic recipe for improving strength and fitness is load + recovery = adaptation. Or as Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness phase it, stress + rest = growth.

Our bodies respond to load by making adaptations, but if we go too hard too often, and/or take too little rest and recovery, the equation becomes out of balance. We lose out on adaptation, and thus our capacity for improvement stalls out.

Strategies like polarization and periodization aim to apply the load/recovery equation to maximize the training adaptations and improvements. Briefly, polarized training is the division of activities into either “hard” or “easy” intensity in roughly a 20:80 ratio. There is no “moderate.” The premise being that moderate efforts are neither hard enough to stimulate adaptations nor easy enough to allow to develop aerobic pathways or for active recovery — putting in “junk miles”, as it’s often described.

In a periodized training program, polarization is taken a step further with hard and easy sessions layered together over longer cycles (think weeks and months). A periodized training plan builds progressively toward a goal race, followed by a period of time following the event that is focused on rest and unstructured training.

During that macrocycle, the split of your weekly training might stay roughly at the 80/20 ratio, but every third or fourth week might be recovery-focused, with a lower volume than the previous weeks. This three to four week block might be called a microcycle. On average, the easy-to-hard ratio is the same, but the overall load of the week is lower, allowing the body to adapt and repair. (And you can catch up on your laundry.)

These fundamental concepts should be incorporated in any good training strategy, whether it’s a week-by-week homemade plan or a comprehensive annual program from a coach. But, just because the plan is intended to provide a roadmap for loading and resting doesn’t mean we will always get the implementation right.

This is not the coach’s fault. It’s life’s fault. A training program is written to balance training load and frequently doesn’t account for the additional stressors of work, school, or family. Stress is stress, regardless of the source. We can’t achieve the intended balance in training if we are over-tired from traveling for work, have been chasing our kids around all day, or burned the midnight oil trying to get our work done when our kids’ school is shut down. Similarly, pushing too hard when we should be going easy leaves us over-cooked before an interval session, deeming it unproductive. But how do we gage the load our body’s have been under?

(If you read the previous paragraphs and said, “This is stupid, I just want to ski” I don’t blame you. I don’t think everyone needs a rigid or even dichotomized workout schedule. However, if all of your exercise is at a hard intensity your risk of injury is increased so you might consider rethinking your strategy. If all of your exercise is at moderate intensity, then you’re just unlikely to get faster. For a lot of people, that’s not a priority, which is perfectly fine and you shouldn’t be judged or dissuaded. Go have fun!)

There’s an old proverb in bike racing about burning matches. Everyone on the starting line starts with the same number of matches. During the race, matches are burned quickly by riding at the front, attacking, covering attacks, and just riding above one’s threshold. At the end of the race it’s often not the strongest rider who wins but the one who burns the least matches (the 2021 men’s Paris-Roubaix is a perfect example).

We, too, start the day with a set number of matches that we’ll burn up with road rage, frustrations at work, frustrations at home, social media FOMO, and of course training. The number of matches we get each day is directly related to how rested and recovered we are heading into the day, both mentally and physically. Exactly how many matches are in the box goes back to recovery, and, once again, to our original question: “How hard should I push myself today?”

If your matches are burnt up before you head out to train, the answer might be “Not very,” regardless of what the training plan says.

One of the earlier attempts to answer this analogue question with a binary “hard or easy”, was resting heart rate. It’s a simple concept: Take your heart rate every morning for a few weeks and calculate an average. If your heart rate has increased by more than 5 beats per minute from the average, then your inventory of matches is not fully replenished. While this article won’t go deeply into the details, there is some research to indicate that resting heart rate doesn’t correlate that well with fatigue levels. This article from Marco Altini goes into significant detail on the topic. (If you follow that link, you’ll find that you’ve arrived on the last of a five part series on Heart Rate Variability. Dr Altini is one of the leading experts and innovators in the field, you may find his articles to be more robust than one you’re currently reading.)

Relative Effort, TSS, EPOC, PTE, CTL, ATL, are all metrics generated by modern wearables to quantify training load and, therefore, stress on the body. These numbers are based largely on heart rate and duration: the higher your heart rate and the longer you keep it there, the more points you score. This is certainly useful information, especially with regards to periodization and keeping track of hard vs easy training sessions; however, it only gives you one number in the load + recovery = adaptation equation.

We still haven’t answered the question, “How hard should I push myself today?”The same device or app that gave you a training load score will likely give a number for recovery status or a time needed to recover; this evaluation is typically still based on average heart rate during training and the overall duration of the previous session(s). It does not take into account the other life stressors. Enter Heart Rate Variability (HRV).

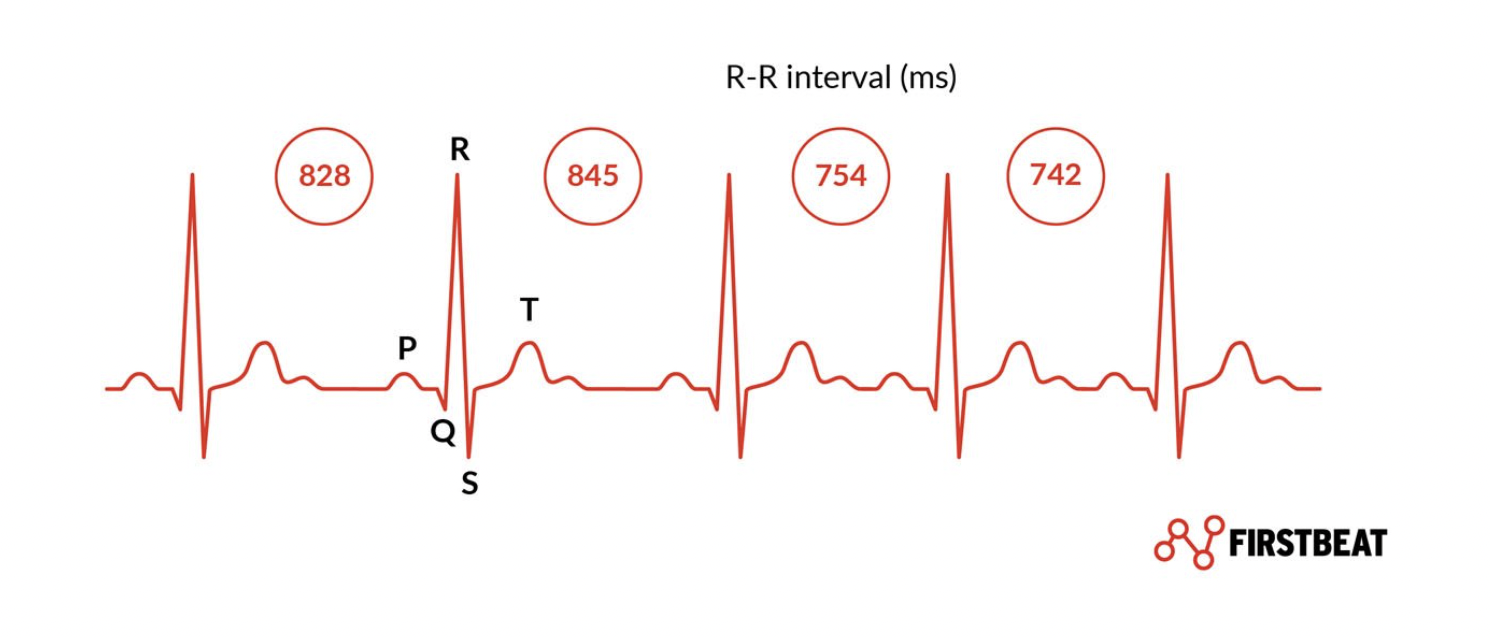

In a nutshell, HRV is a measurement of the time between heart beats rather than the number of beats itself. More specifically, HRV looks at the inconsistency of timing between heart muscle contractions.

Heart rate is governed by the autonomic nervous system, or the division of the nervous system that is responsible for body functions that happen automatically. This is the same part of the nervous system that controls things like temperature regulation (sweating and shivering) and digestion — bodily functions that we don’t have to consciously think about to make happen.

The autonomic nervous system is influenced by the sympathetic nervous system — the “fight or flight” mode that upregulates the body to prepare for battle (heart rate increases, armpits get sweaty, digestion gets turned off, etc.), and by the parasympathetic nervous system, which calms the body down. Our bodies are programmed to seek homeostasis — that happy place where everything can function optimally. The sympathetic and parasympathetic systems work to maintain that balance.

HRV attempts to quantify that balance between the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems, and thus the measurement is a gauge of how the body is down-regulating versus up-regulating — homeostasis.

Somewhat counterintuitively, a higher HRV, which indicates more variability and less consistency in the time between heartbeats, is indicative of greater parasympathetic versus sympathetic influence on the autonomic nervous system. Looked at another way, the greater the stress on the body, the greater the influence of the sympathetic system, which decreases the variability in time between heartbeats and therefore equals lower HRV.

These days, there are many options for recording and tracking HRV: Whoop is a 24/7 wristband with an LED sensor that measures a gazillion things, but specific to HRV, the measurement is taken every night during sleep. The Oura Ring, which is used by some members of the U.S. Cross Country Ski Team, also contains an LED sensor and records automatically during sleep. HRV4Training has an app that turns the camera and flash of your smartphone into a recording device much like a pulse oximeter. EliteHRV uses a device that goes on your finger very much like a pulse oximeter. Firstbeat, who use a proprietary ECG style sensor, were one of the first commercially available HRV trackers on the market (as mentioned in a Nordic Nation podcast with Jim Galanes and in this old article from Zach Caldwell, which also discusses HRV in all the detail you’d expect from Zach).

With all platforms, consistency in recording is key so you can recognize patterns over time. The devices that record automatically during sleep (Whoop, Oura, and Firstbeat) have the advantage in being the no-brainers as long as you’re wearing the gizmo, but they have the disadvantage of being the most expensive. Both HRV4Training and EliteHRV require you to take the recording daily at a consistent time and in a consistent way. Ideally this is first thing in the morning (I go to the bathroom first then immediately sit down and record). I’m a creature of habit and since building this into my morning routine, I’ve not had much trouble incorporating the one minute it takes to record a daily HRV measurement. If consistency is going to be a challenge, invest in one of the automated devices.

This brings us to the utility of HRV: tracking the body’s response to stress over time. The emphasis here is over time. HRV can help answer our question, “How hard should I push myself today?”, but it’s not exactly a stoplight. Waking up to a low score doesn’t necessarily mean you should go easy if you still feel good, but waking up to a seven day average with a negative trend means you should probably skip the hard workouts until your HRV stabilizes. For example, both this paper and this paper found benefits to using HRV to modify training vs strictly following a periodized schedule.

From what we know about the metric so far, the primary goal is to keep HRV stable. If your training plan is appropriately balanced, you’re keeping life stressors in check, and your body is responding favorably, then HRV will remain fairly uniform, even after a hard workout. (A low HRV score after a hard session is definitely not a goal or badge of honor.) But if your HRV becomes unstable, especially a downward trend over at least a few days, that is when it really has the potential to catch an issue while it’s small, whether that’s due to training load, illness, or life stressors. Anecdotally, I’ve heard of notable dips in HRV with people just prior to illness (especially COVID) and after the vaccine. These are situations where maybe you’ve not yet become symptomatic — your body hasn’t started yelling at you — but it is already enduring stress, and the additional load from hard training is not going to be welcomed.

Ultimately, HRV is just another tool in the box. It’s not necessarily there to change what you do on any given day, at least not without subjective input on sleep quality, soreness, emotional state, and how much you drank last night. It’s best viewed as a safety device like anti-lock brakes on your car: if you’re always looking down the road and anticipating what’s to come, you might never need them. But sometimes, when we’re training hard and emotionally invested in our goals, it’s like driving through a snowstorm to make it home for Christmas. It can be easy to focus on the objective outcome and wanting to get there as quickly as possible, rather than slowing down and proactively adapting to the road conditions. Chances are, you’ll make it to your destination unscathed, but in the event that a deer runs across the road or you hit a patch of black ice coming into an intersection, the antilock brakes might help you stop and reset rather than crash.

As Jason Cork, World Cup Coach for the US XC Ski Team, put it, “I think it has some utility as long as you’re honestly also taking into account how you feel, how long you slept, energy, etc. I guess an analogy is if your HR at L3 is usually 180, and you’re super tired, it might be incredibly easy to hit 180 at an L1 velocity or incredibly difficult [to hit all-out velocity because HR is suppressed]. But the question really should be, ‘If you’re tired, why are you doing intensity?’”

Author’s disclaimer: I have no affiliation with any company that tracks HRV. I personally use the HRV4Training app, a Suunto watch, a Wahoo chest strap, and Strava, all of which I have paid for without discount.

Ned Dowling

Ned lives in Salt Lake City, UT where his motto has become, “Came for the powder skiing, stayed for the Nordic.” He is a Physical Therapist at the University of Utah and a member of the US Ski Team medical pool. He can be contacted at ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.