This article is part of a series of interviews with professionals in sports nutrition and female physiology. To get started, you can find a primer on this topic here, and listen to this podcast on Nordic Nation discussing female athlete specific nutrition with registered dietician and professional runner Maddie Alm.

Readers who have followed cross-country skiing for several decades may be familiar with the name Guro Strøm Solli. Now 37-years-old, Solli was a member of the Norwegian National team from 2005-2008, retiring from professional skiing in 2010. During her athletic career, Solli earned two individual sprint podiums and another in the team sprint, and finished 10th in the classic sprint during the 2005 World Championships in Oberstdorf, Germany.

During her athletic career, Solli also earned a degree in exercise physiology, which she built upon in a master’s program after retirement. Now based at Nord University in Bodø, Norway, Solli is working on a PhD which she expects to complete this fall focusing on a variety of aspects of the training of the renowned Marit Bjørgen.

On the side, Solli has been involved in broader research on female athlete specific physiology and effects that the menstrual cycle (MC) has on training and performance. Her article, “Changes in Self-Reported Physical Fitness, Performance, and Side Effects Across the Phases of the Menstrual Cycle Among Competitive Endurance Athletes” published in September 2020 in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance is part of a larger well-funded collaboration between universities investigating exercise physiology specific to female endurance athletes, which in Norway primarily includes cross country skiers.

FasterSkier connected with Solli on a call in January to discuss the findings of the research and how it might benefit female athletes.

In reflecting on her own time as an athlete, Solli does not recall considering her own MC in training and did not experience significant side effects from it. It was not until she began working as a coach of developing athletes and an instructor at the university level that the topic crossed her radar.

“It was not talked about at all [when I was an athlete],” Solli recalled. “It was not a topic that was discussed by the coaches, or even the athletes so much. So that was something I was kind of thinking about — it was nothing that I focused on during my career, but I received a lot of questions from my athletes when I was a coach and also teaching exercise physiology. I experienced that there are a lot of questions, and I started to think, ‘Okay, this is something we need to look into to try to answer all these questions for the athletes.’ So it’s after my career that I’ve been more aware of the topic.”

The research presented in Solli’s article summarized the results of 140 responses to a detailed survey by female Norwegian cross country skiers and biathletes 18-years and older who compete at a national or international level. The questionnaire involved 54 questions regarding age, overall training volume and high intensity training completed during the general preparation and competition periods of a training year, use of hormonal contraceptives, and the prevalence and intensity of side effects such as pain, bloating, mood swings, and appetite changes. Participants also identified when their overall feelings in training and competition were at their best, and conversely when their overall feelings in training and competition were at their worst, and when and to what extent these negative side effects required them to alter or miss training sessions.

“I think an interesting thing that we saw was that over 50% experienced this varied physical shape or training feelings across different phases,” Solli explained. “And there were over 50% that had to actually change their training because of menstrual related side effects. But only 27% had communicated about it and only 7% had planned their training according to the menstrual cycle, so it’s kind of a mismatch between the experience of the skiers and the planning of training. So I think that was an interesting finding, and I think it’s possible to gain something by increasing communication and logging to see if you can find some patterns that work for you.”

An additional statistic that perhaps frames this series of articles is that only 8% of participants reported to have sufficient knowledge about the MC in relation to training, and, as Solli mentioned, just 27% had communicated about it with their coach.

“We asked them why [they had not discussed it], and there was a lack of knowledge, the coach was a man, it was embarrassing, and private,” said Solli. “A lot of athletes didn’t feel the need to talk about it. So it was different topics, but lack of knowledge and that the coach is a man was the most mentioned topic to why it was difficult, so I guess there is still a barrier that there are a lot of male coaches that perhaps have the knowledge but perhaps they don’t dare to talk about this or approach it or know it it’s appropriate.”

Some athlete quotes featured in Stolli’s September, 2020 article include:

- “It feels like it’s a taboo. I am afraid that the coach won’t take it seriously and thinks I’m using it as an excuse.”

- “I think I have more competence and knowledge about this topic than he.”

- “Because he is a man.”

The September, 2020 article also summarizes the importance of this communication, both in terms of athletic development and overall well-being.

“Since menstrual dysfunctions are an important marker for relative energy deficit, a syndrome affecting many aspects of physiological functioning, health, and athletic performance, it is important that athletes feel comfortable to discuss this topic with their coach. Furthermore, because of the high inter-individual variability in performance and side effects experienced by athletes during the MC, coach-athlete communication is important to safeguard the athlete’s health as well as optimize training adaptations and performance. In response, increased attention should be paid to educating female athletes and their support teams about the MC and athletic training.”

Optimistically, Solli continued that she sees the lack of knowledge and communication as a barrier that is in the process of being broken down.

“I have a lot of talks about this with coaches who have wanted me to talk a little bit about the topic,” explained Solli. “And they’re very curious, and they’re starting to realize — you kind of have to get over this being a topic that you don’t mention… Particularly in elite sport, when there are so many topics that are discussed, it’s kind of silly that this topic should not be mentioned as part of the whole situation of an athlete.”

She continued that both research and coach-athlete education on the subject is trending in the positive direction. However, high levels of variation are experienced by women, which makes it challenging to give generalized recommendations.

“It’s starting to be, for the last 2-3 years, kind of a hot topic. I’ve experienced that both coaches and athletes are starting to see that and to investigate if this has an impact [on the individual]. Also, when I read up on the research and meta analysis that are published that try to sum up what we know and what do we not know, it summarizes that we don’t have evidence-based recommendations that can be done on a group level, but it seems like this topic should be approached through an individual.”

Overall, she sees increased awareness and access to information as a positive for female athletes. She noted the increased prevalence of logging apps, such as FitrWoman, that make it easier for athletes to track their cycle and observe trends in their feelings.

In Norway, the possibility to log the MC has also been implemented into the digital training diary that has been designed by the Norwegian Olympic Federation and is used across all sports.

“That’s a step forward, I think. It’s going quite fast in this area, so it will be interesting to see in five years, where are we? I think we will get a lot more knowledge just because athletes are starting to log and discuss this topic. Research takes time, but slowly we will be able to get more studies and more knowledge.”

Zooming out to discuss existing research on the MC and how it might influence the planning of training for elite athletes, Solli noted that a pervasive theme is that the potential for optimal performance can occur during any phase.

“In theory, we expect [hormonal fluctuations] to affect training, nutrition, and performance, but when you look at the meta analysis of how the menstrual cycle affects performance, we don’t have a clear answer on that. It seems like the studies are concluding that on average you can’t see a large difference between the performance in different phases.”

While athletes can rest assured that racing is unimpacted, Solli explained that there are considerations athletes and coaches might apply to training to optimize adaptations.

“When it comes to training effect, there are some studies that highlight that it might be beneficial to periodize your strength training early in the menstrual cycle. This is the phase where you have an increased level of estrogen, which is a hormone with over 400 functions in the body, but two important functions is that it is an anabolic hormone, so it’s good for your ability to build muscle mass, and also important for bone health and to build bone mass and ensure bone density.”

She explained that 4-5 peer-reviewed studies indicate that you can get a higher training effect in terms of muscle strength and muscle mass by periodizing strength training sessions with higher weight and lower reps in the first half of the cycle. Solli added the caveat that, like all research in this area, the studies are often small and the overall topic is still in its infancy.

“It will be interesting to follow the research during the next years to see if we can get stronger evidence in the case of strength training, and whether we’ll also see that we can get some endurance studies, for instance, with periodizing high intensity training in particular phases. We don’t have studies answering that conclusively yet, but it would be exciting to see.”

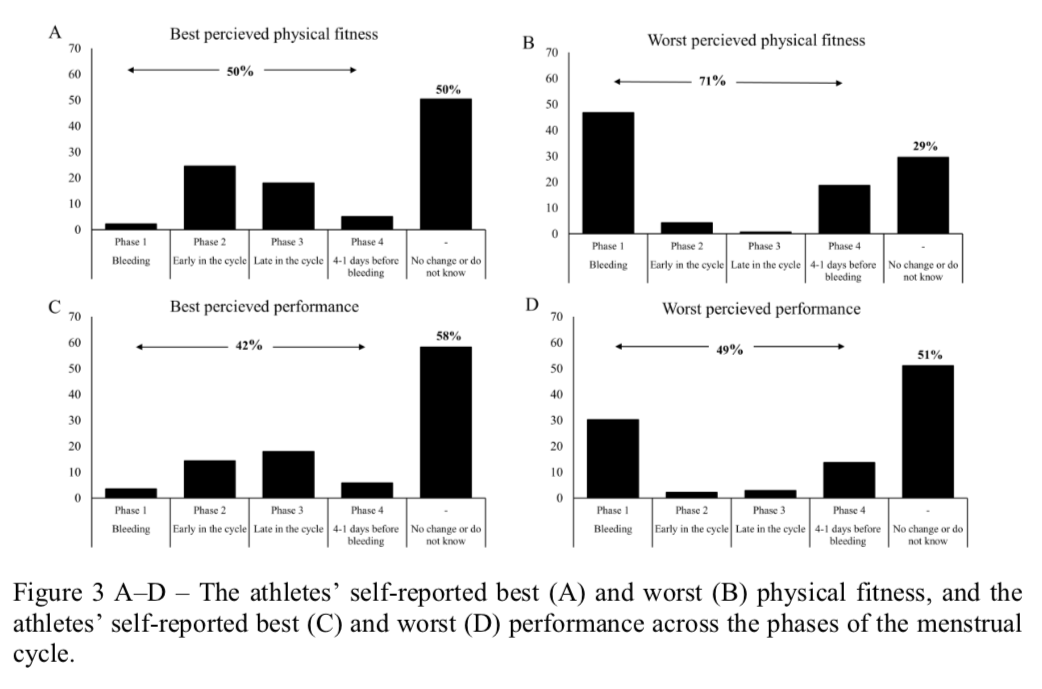

Diving deeper into the survey results analyzed in her study, Stolli discussed the most prevalent themes athletes reported. She also discussed how hormonal fluctuations might explain these effects.

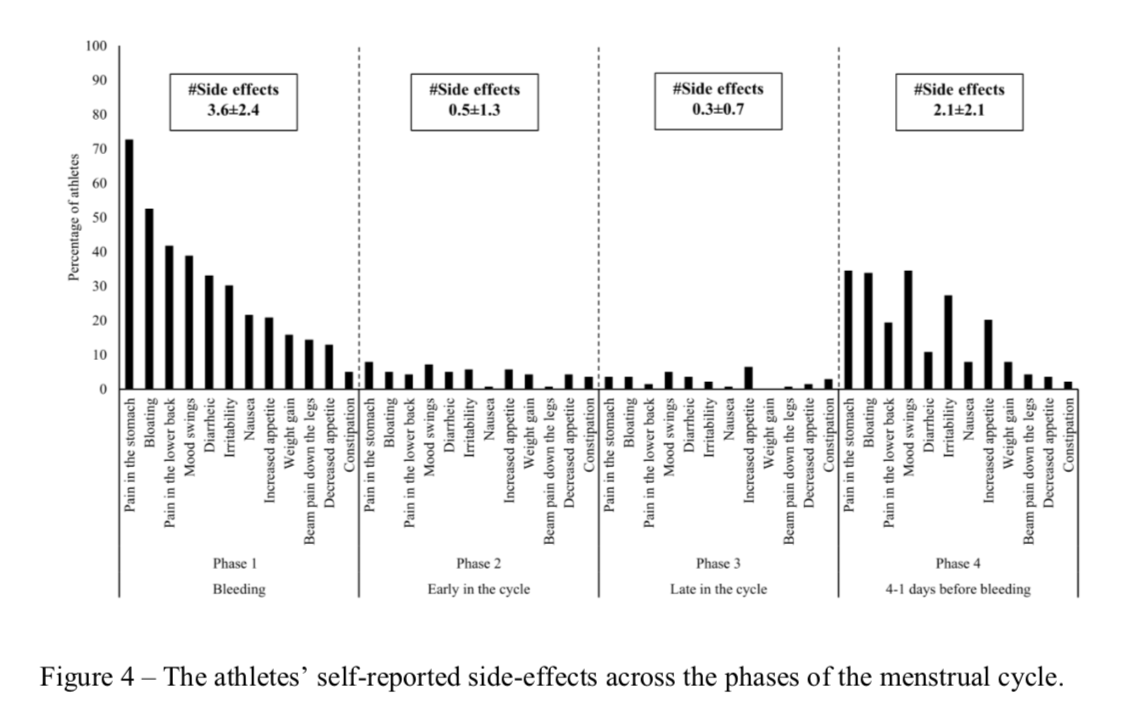

“As we discovered in the study, what the athletes perceive is that the phases where they feel their worst physical shape and have their worst performance was in the days right before the menstrual bleeding and during the bleeding. Right before the menstrual bleeding, we have a drop in both estrogen and progesterone, and this hormone drop is associated with PMS symptoms and different side effects, and we also saw that in our study. The negative side effects reported by the athletes were high during the periods right before and during the bleeding phase.”

This is also the time when athletes most frequently reported using pain-killers to manage symptoms and needing to alter their training by decreasing volume or intensity.

“I guess that is not only my study, but also other studies highlight that those two periods can be a risk for decreased training quality or that the athletes don’t manage to perform the training they have planned because they are experiencing these negative side effects.”

In contrast, most athletes perceived their best fitness was achieved during the middle phases of the cycle. This coincided with the window where negative side-effects were least reported.

Another noteworthy statistic Solli touched on was hormonal contraceptives (HCs), which 56% of athletes reported using. The fact that HCs were not broken into subcategories such as oral contraceptives, IUD, etc., was listed as a limitation of the study.

“A large proportion of the athletes are using hormonal contraceptives,” said Solli in the call. “And there are a lot of different types with different amounts of synthetic estrogen and progesterone that suppresses the normal hormonal fluctuations, and you get a more stable cycle. As we saw, there were positives experienced with using HC’s that athletes reported that they get reduced pain and they also get control of the bleeding phases, so they can control it according to their competitions or trainings. But there are also some negative effects with weight gain and irregular bleeding.”

Solli explained that there is little research apart from survey data pertaining to how HC’s might affect female athlete performance and, similar to experiences with a natural cycle, the side effects women experience vary considerably. Here too, Solli recommended considering each athlete and situation as unique, advising athletes to pay close attention while adjusting to new or different forms.

“From research, when they compare using HC to having a normal menstrual cycle, most studies show that there is no effect on performance and that also performance is relatively consistent across the HC cycle,” Solli explained. “Also here, an individualized approach based on each athlete’s response is recommended from research, because you see that from some athletes they report more negative side effects, so that’s important to find a type that suits you and to log the effects when starting a new type.”

Of the athletes not using HC, a noteworthy 35% reported fewer than nine periods per year, an indicator of menstrual dysfunction possibly due to low energy availability, meaning the caloric and/or nutrient density of an athlete’s diet does not meet the demands of their training. While this may be unintentional, the condition known as Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) is prevalent in endurance sports, particularly those that favor leanness. It is often associated with disordered or restrictive eating behaviors.

RED-S can cause a cascade of negative health impacts, from hormone imbalance, to low bone density, to impaired immune function, and cardiovascular problems.

“Although we did not assess energy intake or energy expenditure,” the article states, “high volumes of training and high amounts of high-intensity endurance training are associated with high energy expenditure and can prompt relative energy deficiencies. Elite endurance athletes and their coaches should therefore be aware of the risk of MC irregularities induced by high volumes of training and high amounts of high-intensity training. The prevention of MC irregularities should also be pursued, because primary and secondary amenorrhea can result in adverse health conditions, including reduced bone health.”

At the World Cup level, this phenomenon has made FasterSkier headlines in the cases of Norway’s Ingvild Flugstad Østberg and Sweden’s Frida Karlsson, who were pulled from competition last season by national team doctors after failing to meet team health metrics. Østberg resumed competition for the 2020 Tour de Ski, where she finished third, and competed through the first weekend of racing in March in Falun. Her season then ended abruptly after she sustained a stress fracture in her foot from hopping off a three foot cement step to the ground.

The 30-year-old Østberg sustained a second stress fracture in July and has not competed on the World Cup this season. Østberg has been working with team doctors to bring her body back to health in order to compete in the 2021/2022 World Cup and Olympic season.

Karlsson was withheld from competition from early December, 2019 to February 9th, 2020 and has remained in competition since. More recently, Finland’s Kerttu Niskanen sustained a fracture in her tibia during a race in Falun that was not caused by a crash. FasterSkier has not received further insight into her situation.

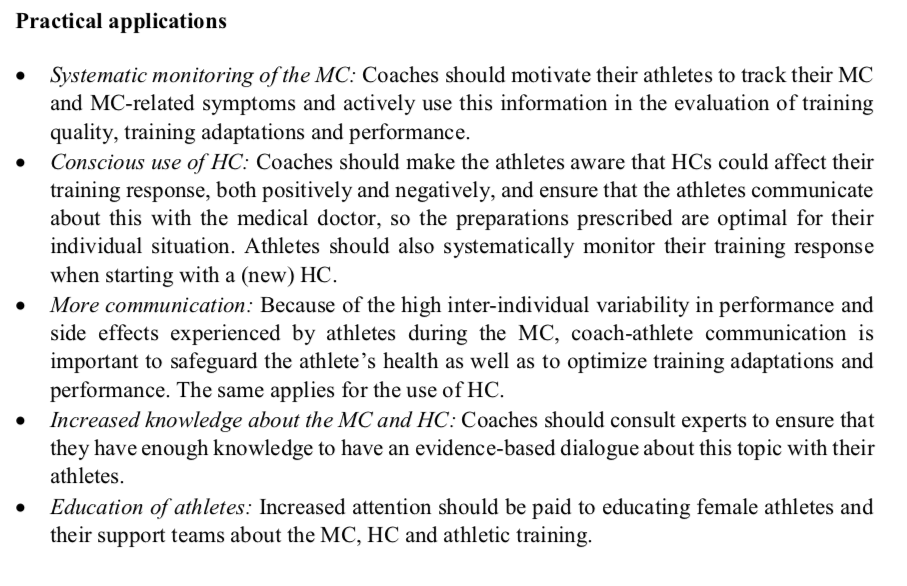

Bringing it all together with the information Solli discussed in mind, how should athletes and coaches approach this topic? Solli’s article lists a set of practical applications of the information currently available.

Solli concluded that understanding the MC and how it might influence training and performance is just one piece of the puzzle of female athletic development. She stated that hype from media attention might make it seem essential, but for many who do not experience significant effects, this area might not be worth investing in. However, for many athletes, better understanding and communication could lead to significant improvement. For this reason, Solli recommends an individualized approach, adjusting the focus based on the extent to which an athlete is impacted.

“It is a part of a lot of different [aspects of training],” said Solli. “So you have to look at it in the bigger picture, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t need to talk about it. You can’t ignore it, but you should not make it too big of a deal if you aren’t struggling with it and you have a natural cycle and everything is okay, I don’t think you need to change something. But I think some athletes are struggling with it and I think they should know that it’s possible to get help.

“There is a lot of information now, a lot of good articles that are published, and information in the apps — I think it’s really good for young athletes to start there and to log [their cycle] and learn. That’s something I really would have wanted when I was a young athlete, that I could have an app and to start early to find my own pattern that I could optimize. I think that’s a really good opportunity to learn how your body works.”

Rachel Perkins

Rachel is an endurance sport enthusiast based in the Roaring Fork Valley of Colorado. You can find her cruising around on skinny skis, running in the mountains with her pup, or chasing her toddler (born Oct. 2018). Instagram: @bachrunner4646