This is Part 4 of a series delving into how biomechanics and movement patterns affect skiing technique. If you haven’t already, start with the introduction, Part 1 which introduces the concept of a neutral spine posture, Part 2 which describes spine stability and mobility, and Part 3 on single limb stability.

——————————————–

Upper body power is a major contributor and perhaps even a determinant of cross country skiing performance. Poling accounts for up to 60% of propulsion in skate and classic diagonal and, obviously, 100% with double pole. For those who train for skiing year round, upper body work is an essential part of the routine. However, for those whose summers are focused on running, cycling, or hiking, arm strength is often forgotten once the snow melts.

Let’s take a closer look at the structures and muscles involved in the upper body during the various poling motions of skiing.

The muscles that comprise the shoulder girdle can be roughly divided into two groups: the stabilizers and the movers. Coordinated motion requires “dynamic stability”, i.e., for the two groups to together such that the stabilizer muscles control extraneous joint motion while the movers perform the primary action.

The shoulder has a tremendous amount of motion available and relies heavily on the coordinated effort of multiple muscles to maintain proper alignment and movement of the joint. At the same time, it is capable of generating large amounts of power, whether that’s throwing a 90mph fastball, hammering a nail, or repeatedly pushing on a ski pole.

The shoulder stabilizers can be further divided into those acting on the glenohumeral joint (the primary ball-and-socket shoulder joint) and those supporting the scapulothoracic joint (shoulder blade on the ribcage).

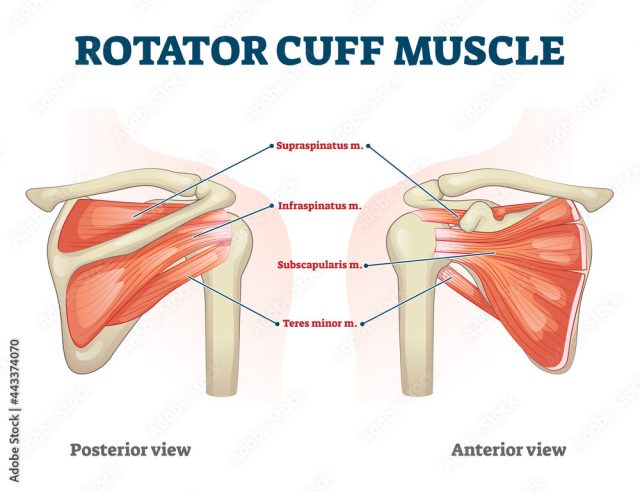

The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles — supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis — that attach to both the scapula and humerus in close proximity to the joint. They are not particularly strong muscles, but they play a vital role in coordinating the movement of the glenohumeral joint.

The only rigid or bony attachment of the arm to the body is via the collarbone. This small bone is not enough to support the load of push ups, pull ups, or double poling. The base of support truly lies in the muscular attachment of the shoulder blade to the ribcage. For the sake of the simplicity of this article, we’ll limit the discussion to four muscles, one of which doesn’t count. (Side note: a classic physical therapy trivia question is to name all 17 muscles that attach to the scapula–clearly I’m skipping a few here.)

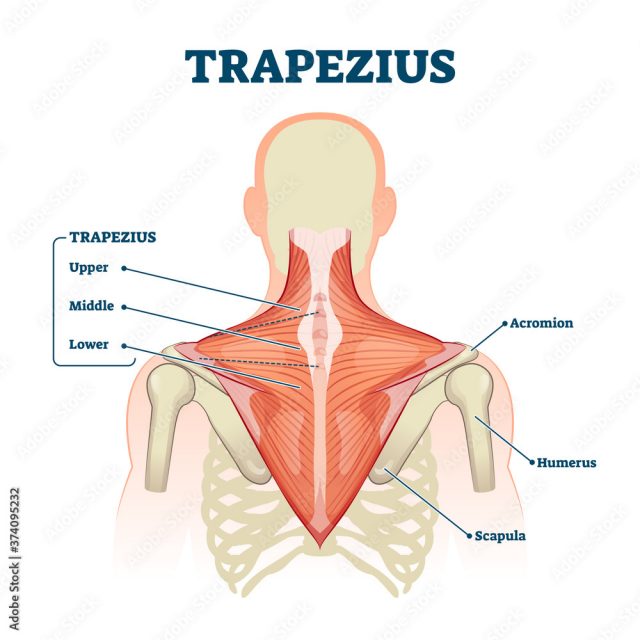

The primary stabilizers of the scapular are lower trapezius, middle trapezius, and serratus anterior. I’ll contend that the upper trapezius is a stabilizer but doesn’t count because it tends to exert force in the wrong direction (and is frequently overactive so needs little in the way of direct strengthening).

As with any dynamic stability in the body — abdominal muscles for the lumbar spine, glutes for the hip, or the aforementioned muscles in the shoulder girdle — strength is important but intermuscular coordination is key. This is especially true at the shoulder due to its wide range of available motion and corresponding muscular complexity.

The following are exercises targeting the stabilizers, both at the shoulder joint and scapula.

Exercises for the Stabilizers:

(The intent of these exercises should be thought of more as activation drills and less about the heaviest weight you can find. Yes, we are looking to induce some fatigue but the emphasis is not on power.)

Side Lying External Rotation: Lie on your side. Keep the top elbow bent at 90° and against your side. Rotate about the shoulder until your forearm is at about 45° to the horizontal. Try not to pull with your shoulder blade. A little bit of weight goes a long way.

External Rotation + Uppercut: With a resistance band anchored on the opposite side, elbow fixed at 90°, and forearm against your belly. Rotate the forearm away from the belly to a neutral position (knuckles pointed forward). Then raise the arm by spinning through the shoulder. Again, the elbow should stay at 90° throughout. Only raise the arm to shoulder height. Motion should be isolated at the shoulder joint — don’t let the shoulder blade move. Finish by lowering the arm down and rotating the forearm back to the belly.

Scaption: Raise both arms up your sides at 45° (not in front, not to the side, but halfway in between). Stop at shoulder height. Keep the shoulder blades fixed down and back. Start with light weights.

Wall Slides: Loop a very light resistance band around both hands and stand facing a wall. Place both hands on the wall at about shoulder heights with elbows bent and palms facing inward. Stretch the band by squeezing your shoulder blades down and back, not just pulling from the arms. Keep the shoulder blades pinned down and back, band tensioned, and slide your hands up the wall until your elbows are at about shoulder height. Slide back down to the starting position. Ideally, the shoulder blades stay retracted throughout the set of repetitions, but you can stop and reset them between reps or as needed.

Serratus Punch: The serratus anterior muscle attaches to the ribcage, inserts on the scapula, and, acting alone, protracts the scapula, or pulls it forward. As a stand alone movement, this scapular protraction is not especially functional unless you are a boxer hitting with a jab. However, the serratus anterior is a team player and becomes very functional when co-contracting with the posterior scapular muscles (especially middle and lower trapezius) to stabilize and coordinate movement of the scapula. The exercise will work the serratus anterior independently.

Lie on your back holding a dumbbell in each hand. Knees are bent and elbows are straight. Push the dumbbells towards the ceiling by moving the shoulder blades forward on the ribcage. This is the opposite of the motion described in Wall Slides. The neck and thoracic spine stay relaxed. This can also be done with a resistance band.

Rows: The emphasis of the rowing motion is on squeezing the shoulder blades down and back as you pull the resistance towards you. This is the same motion described in Wall Slides and the opposite of the Serratus Punch. There are multiple means of adding resistance to the movement: resistance band, cable machine, single dumbbell/kettlebell, TRX, etc.

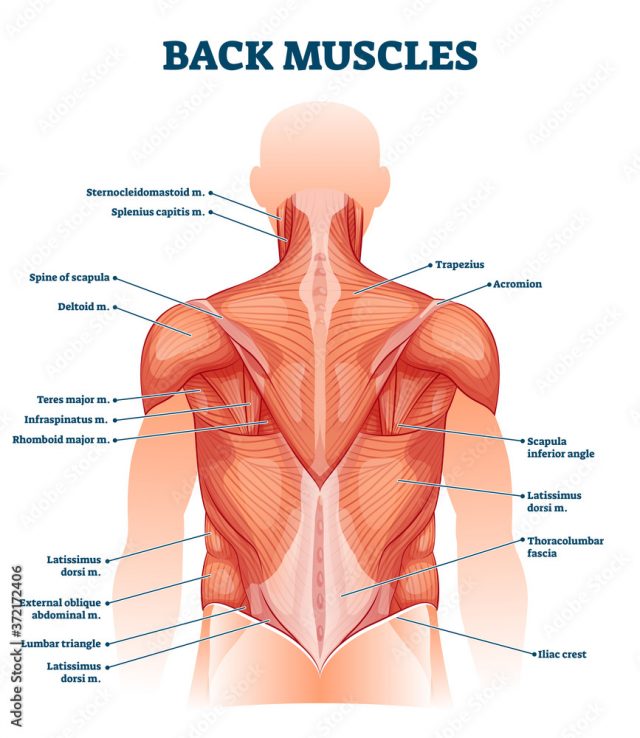

In the propulsive phase of poling, the prime mover at the shoulder joint is the latissimus dorsi — often referred to as the “lats”. This big, broad muscle extends the shoulder, pulling an outwardly extended arm to the side as in freestyle swim strokes and pull ups. The lats are aided by the posterior portion of the deltoid muscle and teres major.

The elbow joint is also involved with the triceps playing a rather complex role. This muscle, or more technically speaking, this group of muscles has a common insertion on the ulna and acts to straighten the elbow. However, the long head of the triceps, attaching to the scapular vs the humerus, is also able to play a role in shoulder extension. I say the triceps play a complex role because motion about the elbow varies with technique and terrain. In Skate V1 and V2 alternate and in Classic striding, there is a fair amount of elbow extension. However, in V2 and uphill double poling, there is very little motion at the elbow.

Notice how little motion takes place at the elbow during V2.

A clinical case study: (Disclaimer: the subject of this case is the author, a potential duplicity that is frowned upon in academia.) In the lead up to ski season, I began doing “budget SkiErg” workouts double poling with resistance bands. After several weeks of twice a week workouts, I began to develop left posterior elbow pain. It didn’t take much to figure out I had irritated the insertional tendon of the triceps. So I stopped the workouts and focused on eccentric strengthening of the triceps, which has become the standard of care in the treatment of tendinopathies.

Come ski season, I could skate without any problems, but I continued to have elbow pain with more than about 45 minutes of classic. One night at dinner I was venting to my wife about my now chronic elbow pain. Ever the voice of reason, she asked what I would do if I was seeing myself in the clinic. What would I, the PT, do differently for a patient who is not responding? I replied that I would examine, biomechanically, how the patient is poling. So I started to think about how I was doing what I was doing.

My hypothesis was that I was using my triceps too much to generate shoulder extension. I started doing shoulder extension exercises with my elbow fixed at 90°. I focused on leading the motion with the back of my elbow, not my hand. Within a couple of weeks, the elbow pain was gone. The lesson from my mistake is that functional movement patterns often require a high degree of coordination. Because of our bodies’ anatomical redundancy, it is easy to fall into a suboptimal pattern that is inefficient in the best case and in the worst has potential for injury.

Interestingly, the biceps appear to be very active during double poling, which seems counterintuitive since the action of the biceps is in the opposite direction of the propulsive phase of poling. The biceps do contribute to shoulder flexion so they are likely involved during the return phase. But, more likely, the majority of their action is co-contraction with the triceps to stabilize the elbow and hold it in the desired position. Perhaps this is rationale to include some biceps strengthening for more than just filling out the sleeves of your cycling jersey.

Exercises for the Movers:

Shoulder Extension: This is most easily done with a dumbbell, but a resistance band will work as well. As described in the case study, keep the elbow locked at 90° and focus on spinning at the shoulder joint by leading with the back of the elbow.

Strengthening the Triceps: Like with Rows, there are numerous ways to work the triceps with no single exercise being the best. Resistance band, cable machine, dumbbell, push ups, and dips are all appropriate.

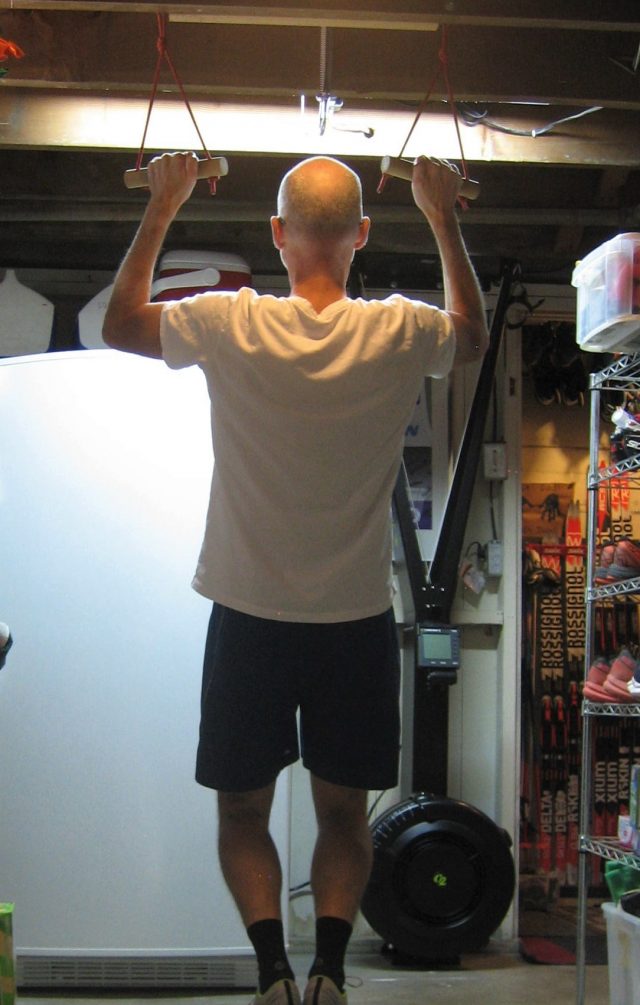

Strengthening the Lats: The basic lat workout is pull ups. If these are too difficult to do at least 3 reps, then put your feet on a chair or on a long resistance band loop attached to the pull up bar (just make sure the band stays on your feet and not in between them!). Lat machines in the gym are a great alternative as you can select resistance that is lighter than body weight (or more than body weight if you can whip out 10+ regular pull ups)

Epilogue: The goal of the Building a Better Skier series has been to identify some key biomechanical and kinematic components of cross country skiing and to provide exercises with the specific intent of facilitating these movement patterns and strength requirements. By no means has the depth of these articles been exhaustive. Nor have the lists of exercises covered all possibilities. Hopefully, these articles have been easy to follow and the exercises have been included in your twice weekly strength/dryland/pay-to-play routine. Even better, I hope the work done now will pay dividends when the snow falls this winter. Best of luck with the remainder of summer (the heat, the smoke, the pandemic), the glorious autumn, the struggles of shoulder season, and the winter we’ve all been waiting for.

Ned Dowling

Ned lives in Salt Lake City, UT where his motto has become, “Came for the powder skiing, stayed for the Nordic.” He is a Physical Therapist at the University of Utah and a member of the US Ski Team medical pool. He can be contacted at ned.dowling@hsc.utah.edu.