Last year, in an effort to create a standardized workout that could be easily replicated and repeated, national team coaches presented the concept of the “U.S. Pace Project.” The concept is straightforward: a shift away from time-based intervals to distance-based, centered around repeated laps of a 5-kilometer course.

This familiar distance is key. In a call in July, Matt Whitcomb, U.S. Ski Team Head Coach, and one of the creators of the project explained that: “5k is essentially the building block of just about every race we ever do. It’s a very tangible distance that everybody knows right from childhood.”

Whitcomb continued that while the session itself is not revolutionary, it has provided a shared pathway for clubs to explore pacing during intensity sessions. Usually athletes will complete three rounds of the same 5k course, and repeat the workout intermittently throughout the training season to track overall progress or fine-tune pacing strategy. Given the ease of implementation, clubs of all levels nationwide can adopt the concept.

“Clubs are encouraged to find a 5 kilometer stretch of rolling road, something that can replicate race terrain as best and as safely as they can,” Whitcomb explained. “If it’s on a rollerski track, that’s even better.”

As the training year progresses, so does the nature of the Pace Project. “This is a workout that is meant to build in intensity throughout the year, but also in creativity,” Whitcomb stated.

Creativity, in this context, is an ongoing experiment with pacing, fueling, technique, and effort, followed by a discussion of individual outcomes amongst the group. Essentially, the U.S. Pace Project is a personal study for athletes to find their own fastest and most efficient approach to racing.

Another motive behind the project, according to Whitcomb, is to promote the sharing of insights between athletes and coaches nation-wide as they incorporate and discuss the takeaways from the Pace Project format. He explained that time-based intervals offer less concrete information to learn from, as there is more room for variation in training venue and conditions.

“[The sport] is challenged with regards to metrics,” Whitcomb said. “So this is meant to catalyze more objective feedback and learning.”

As many national team members train in Stratton, VT in the summer, SMS T2 head coach Pat O’Brien provided a look into his experience facilitating the workout with his athletes and his current takeaways.

“If you give the athletes a set distance workout, they are going to learn how to manage their energy over that distance,” O’Brien said, citing supporting research by Norwegian based Sports Science Professor Steven Seiler.

“The whole point,” O’Brien continued, “is in a training type environment, go out and play around with different [approaches]. It might not all work. It might fail. But it’s better to learn those lessons in a training environment than in a race.”

While a nationally shared workout is new, the project itself grew out of conversations with previous American athletes who incorporated similar workouts as a fitness benchmark.

“I think the most notable one is Kris Freeman,” O’Brien explained. “He was truly one of the best in the world at the 15k distance. He would do a repeated workout of 3x5k, and he knew if he could sustain three repeats on [a particular] 5k stretch of road, he was in good shape.”

O’Brien said that inspiration had also come from one of his mentors, Sverre Caldwell, former Nordic Director at SMS.

“Back in the early 2000s, the Stratton program had a string of successes with high schoolers going on to these great sprint results when sprinting had just started coming out,” he said. “What was interesting talking to [Caldwell] was they didn’t go out seeking to pace sprints. He wanted to make his athletes stronger and tougher, so he devised a double pole test.”

The test involved double poling up a specific hill, which happened to take high schoolers like Andy Newell about three minutes. “It was not intentional, but they got good at figuring out how to go up that hill as best they could for about three minutes, which happened to be about how long a sprint was. They didn’t go out with the intention of being great sprinters, but if you give the athletes a set distance workout, they are going to learn how to manage their energy over [that distance].”

These ideas have fused into the Pace Project. Still in its infancy, it remains an elastic concept meant to help American skiing in a number of ways. Part nationally shared workout, part personal experimentation project, part data gathering opportunity, there are many objectives at play.

“The pacing project is an idea where if we subject ourselves to all these different stimuli, we can be more flexible,” O’Brien said. “The point is, we’re always going between environments, and we’re always trying to get athletes better at finding what their red line is, so to speak.”

O’Brien explained that coaches had been seeking a way to reap the benefits of racing without the physiological toll they require.

“How can we construct workouts that challenge you in a similar way to what you experience in a race without the same cost?” he asked rhetorically.

The Pace Project seems to be filling this gap, by offering athletes a chance to experiment with novel pacing strategies outside of a race environment.

“I don’t care if someone goes into it too hard and blows up,” said O’Brien. “We’re not looking for an objective time, It’s about how athletes pace themselves.”

O’Brien stressed that the key to the pace project lies in athletes figuring out what works best for them, both in what technique they use on specific sections of the course, and for overall pacing.

“Every athlete has a style,” he said, “a way they want to move. [It’s] not ‘you should do this because it works for you.’ I think that’s how we unlock our athletes’ best potential.”

The Pace Project has received favorable reviews from athletes and coaches beyond the SMS T2 team. The SVSEF Gold team in Sun Valley, Idaho use their 1.2k rollerski trail for pace sessions according to Head Coach Chris Mallory.

“This workout basically brings a little more focus to threshold workouts,” wrote Mallory in an email. “Athletes can play around with different pacing strategies, whether it’s starting more conservatively, using different techniques, or skiing different parts of terrain harder or easier to see what works best for them… It’s nice to have something that’s repeatable, where you can measure progress.”

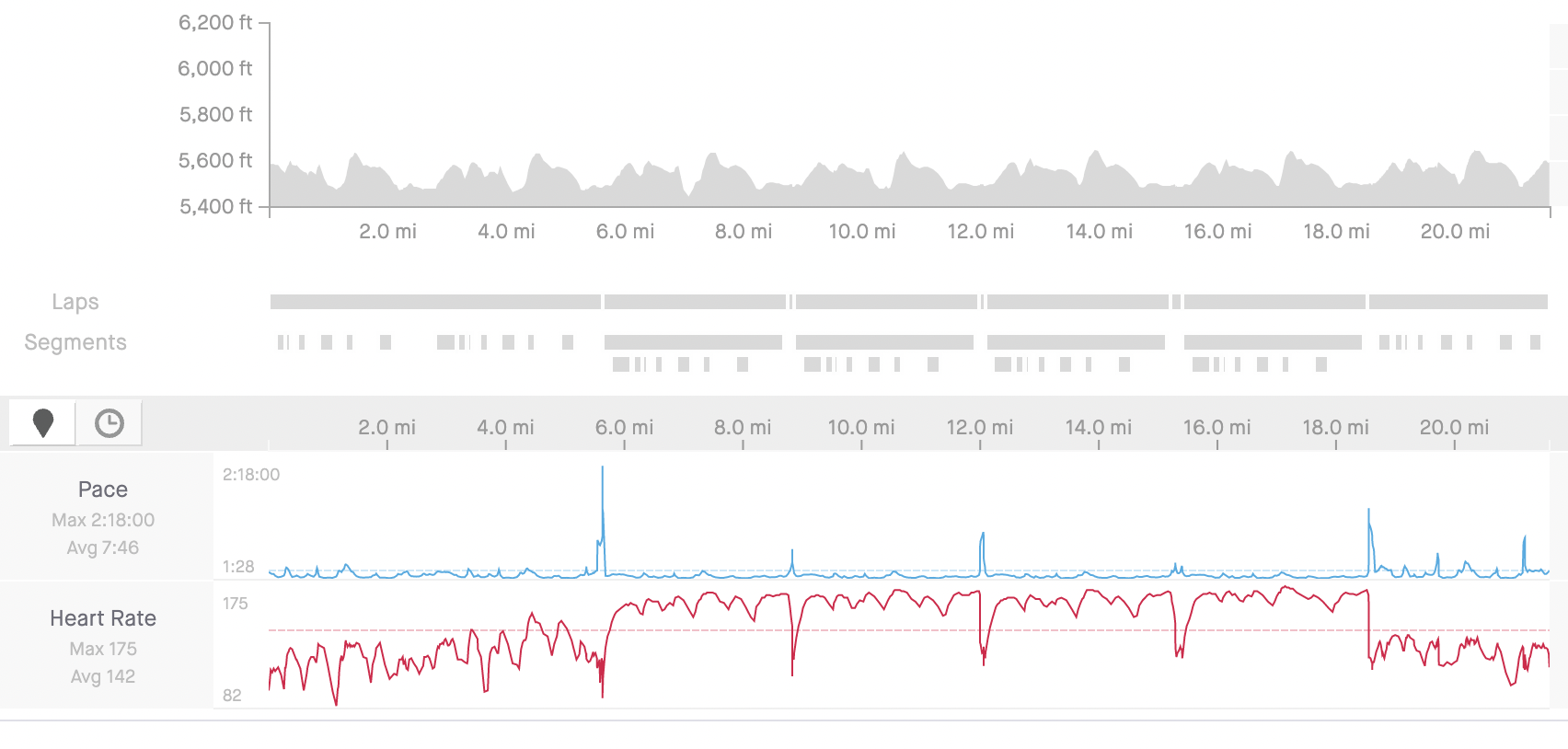

Strava users who follow some of the top domestic skiers may have seen some of them completing these workouts, like this example of Gus Schumacher’s October iteration. Schumacher explained in an email the role the workout has played in his summer training this season:

“[The Pace Project] is a cool format because it allows for a lot of different strategies, similar to racing. Usually in the earlier summer we’ll use it as a way to get L3 while lapping a track with similar features to a race course. Later however, like at our camp in Park City, it was fun to use it as almost a race simulation.”

Schumacher described one of his sessions in October: “I started the first 2 minutes hard like I would in a mass start,” he wrote. “After that I eased back to a sustainable pace, then in the last one I finished hard. This made it feel a lot like a race without the same cost (because of 3 minute rest between each interval). Breaking it up into segments also allows us to change our strategy more from lap to lap, which can help with testing new pacing strategies, especially at altitude.”

Reflecting on the outcomes for coaches, Whitcomb said that he was pleased with how the Pace Project sessions had increased the conversations between athletes.

“What we’ve observed is that there’s more interesting discussion before and after these sessions, than there is for just your standard threshold interval workouts.”

Over the summer, Whitcomb stopped by Stratton during a SMS T2 pace session and remarked on the depth, variety, and value of the subsequent conversations.

“Of the ten athletes that were there that day, there were ten different approaches to this workout, because Bill Harmeyer is setting his sights on one specific goal on that day, and Jessie Diggins on perhaps another goal, and everybody’s learning and discussing and crowdsourcing ideas effectively.”

While the value of the project lies in its idiosyncratic freedom, the aim is competitiveness.

“Hopefully,” Sun Valley’s Mallory suggested, “it helps our nation to continue to make progress in distance racing.”

Pasha Kahn

Pasha Kahn writes and coaches in Duluth, Minnesota.